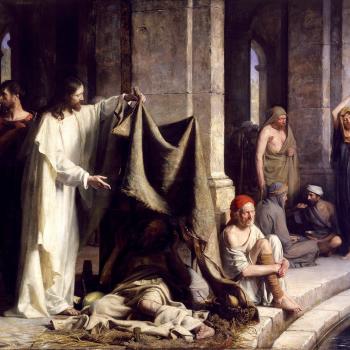

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

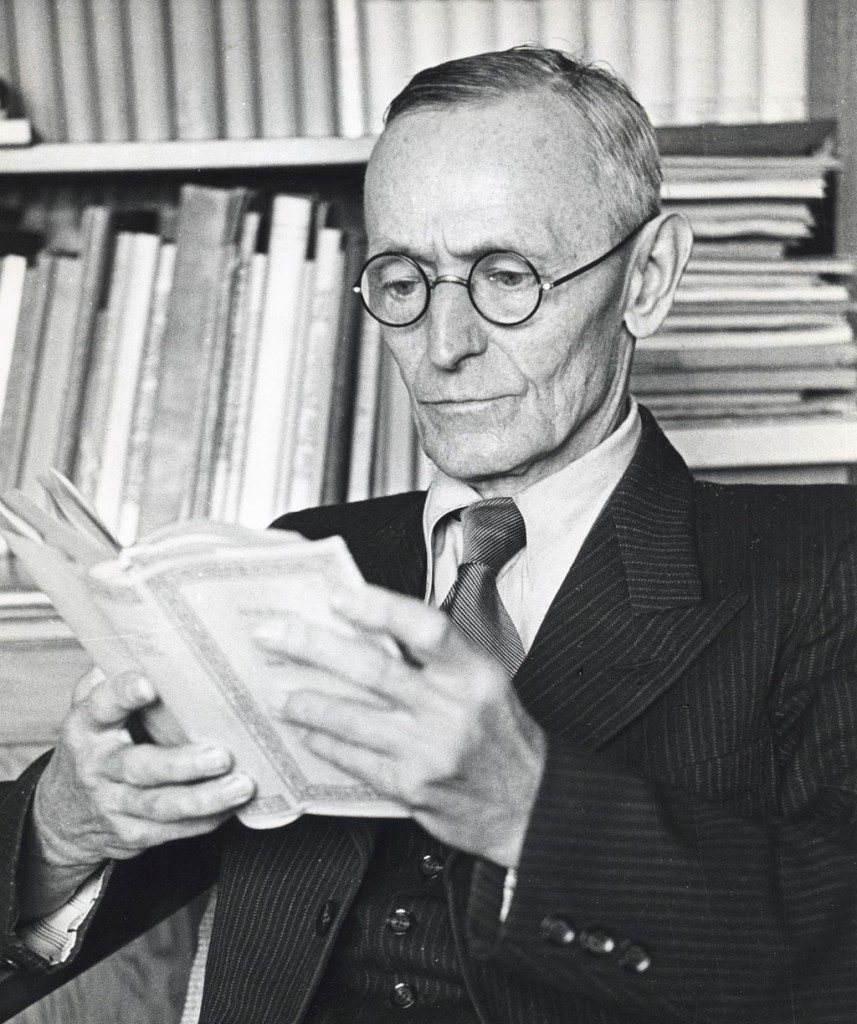

I’ve been re-reading the novella Siddhartha, by the German-born writer Hermann Hesse (1877-1962). Here, in my translation from a German edition published somewhat enigmatically by “Will Jonson and Dog’s Tail Books” in the United Kingdom, is a passage that struck me last night, in which the title character, Siddhartha, addresses Gotama, the Buddha. Siddhartha’s lifelong friend and follower, Govinda, has just become a disciple of the Buddha, but Siddhartha has been unable to take that step:

Everything in your doctrine is perfectly clear, is proven; you present the world as a perfect chain that is never and nowhere broken, an eternal chain forged from causes and effects. Never has this been seen so clearly, never so irrefutably set forth; truly, the heart of every Brahman has to beat stronger with love, once he has glimpsed the world through your teachings as perfect connection, without gaps, clear as a crystal, not depending on chance, not depending on gods. Whether it is good or bad, whether living according to it would be suffering or joy, remains to be seen (perhaps this is not essential) — but the unity of the world, the interconnection of everything that happens, the enclosure of all things great and small within the same current, by the same law of causes, of coming to be and of dying, this shines brightly out of your exalted doctrine, O perfected one. But according to your very own doctrine, this unity and necessary sequence of all things is nevertheless broken in one place; through a small gap, this world of unity is invaded by something alien, something new, something that had not been there before and that cannot be shown and cannot be proven: That is your doctrine of overcoming the world, of salvation. However, with this small gap, with this small breach, the entire eternal and uniform law of the world breaks apart again and is nullified. Please forgive my expressing this objection.

Alles in deiner Lehre ist vollkommen klar, ist bewiesen; als eine vollkommene, als eine nie und nirgends unterbrochene Kette zeigst du die Welt[,] als eine ewige Kette, gefügt aus Ursachen und Wirkungen. Niemals ist dies so klar gesehen, nie so unwiderleglich dargestellt worden; höher wahrlich muß jedem Brahmanen das Herz im Leibe schlagen, wenn er, durch deine Lehre hindurch, die Welt erblickt als vollkommenen Zusammenhang, lückenlos, klar wie ein Kristall, nicht vom Zufall abhängig, nicht von Göttern abhängig. Ob sie gut oder böse, ob das Leben in ihr Leid oder Freude sei, möge dahingestellt bleiben, es mag vielleicht sein, daß dies nicht wesentlich ist — aber die Einheit der Welt, der Zusammenhang alles Geschehens, das Umschlossensein alles Großen und Kleinen vom selben Strome, vom selben Gesetz der Ursachen, des Werdens and des Sterbens, dies leuchtet hell aus deiner erhabenen Lehre, o Vollendeter. Nun aber ist, deiner selben Lehre nach, diese Einheit and Folgerichtigkeit aller Dinge dennoch an einer Stelle unterbrochen, durch eine kleine Lücke strömt in diese Welt der Einheit etwas Fremdes, etwas Neues, etwas, das vorher nicht war, and das nicht gezeigt und nicht bewiesen werden kann: das ist deine Lehre von der Überwindung der Welt, von der Erlösung. Mit dieser kleinen Lücke, mit dieser kleinen Durchbrechung aber ist das ganze ewige und einheitliche Weltgesetz wieder zerbrochen and aufgehoben. Mögest du mir verzeihen, wenn ich diesen Einwand ausspreche. (21-22)

In this passage, Hesse sets forth a Buddhist conception of the cosmos and of human life as expressing an unbroken chain of cause and effect, without gaps, with no room in it for gods or divine grace. It is, to borrow a Protestant conception, a world of salvation — if, indeed, there is to be salvation — by works. The message of Christianity I take to be dramatically opposed: Salvation occurs when and where Christ intervenes to break the iron law of cause and effect, of karma, of justice. Mercy enters the world from the outside.

I wonder, though, why it was that modern science, as we know it, arose in the theistic West, with its interventionist God, rather than in the Buddhist lands, dominated as they were and are by a conception of the universe as a closed system of cause and effect. One might have thought that the latter, rather naturalistic view would have been more conducive to the rise of science. But it wasn’t.