(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I was struck by Theodore Dalrymple’s review of Jérôme Fourquet’s L’archipel française: naissance d’une nation multiple et divisée on pages 56-58 in the December 2019 issue of the superb magazine First Things, to which I subscribe. The reviewer, Anthony Malcolm Daniels — Theodore Dalrymple is a pen name — is an English cultural critic, prison physician, and psychiatrist who worked both in Great Britain and in sub-Saharan Africa before his retirement from medicine and who currently divides his time between England and France.

L’archipel française translates into English, of course, as The French Archipelago. The term archipelago refers to an island group or island chain, to a chain or cluster or collection of more or less scattered islands. The Hawaiian Islands or the Aleutian Islands would be good illustrations of the idea. As will be seen, the word is precisely relevant to Jérôme Fourquet’s argument:

The decline of Catholicism in France is paralleled by the decline of both Anglicanism and non-conformist Protestantism in Britain, and the sudden appearance of a religion new to both countries, Islam, gives rise to parallel currents of anxiety. Moral boundaries in both countries have melted away like snow in spring, leaving behind a rampant individualism. . . .

Fourquet’s thesis is that French society is breaking up into mutually uncomprehending and sometimes hostile social islets, separated not only geographically but by the tastes, culture, education level, and economic prospects of their inhabitants, who have little contact with or sympathy for one another. . . .

Fourquet begins his analysis with an account of the precipitous, indeed astonishing, decline of Catholicism in the nation that once was called the Eldest Daughter of the Church. The decline has been so thorough that I once found a recent edition of Flaubert for students that explained in its notes what the Trinity and sacramental confession were, presumably because many pupils would not otherwise know. Only 5 percent of French Catholics now attends church weekly, and even such vestigial sacraments as baptism are declining rapidly (perhaps not surprisingly, since nearly 60 percent of births in France occur out of wedlock). The number of priests has declined by more than half between 1990 and 2015, and given their advanced age and the lack of new vocations, soon there will be practically no French priests at all. The few who remain will be African or Filipino.

In 1900, 20 percent of newborn girls in France were named Marie, the number varying with the degree of local attachment to Catholicism. Today, Marie is a name rarely given to anyone anywhere in the country. A law passed in 1803 required that all children in France be given one of two thousand names, mainly those of saints. But at the end of World War II, the law began to be ignored, and the numbers of names given to children began to increase. By the time the law was repealed in 1993, it was a dead letter, and today the number of names given to newborns each year stands at 14,000, not including the 55,000 names (one in fourteen births) bestowed on not more than three children in a given year, many of which are completely made-up. Fourquet sees in this trend the rise of mass narcissism, the need to make one’s mark merely because it’s one’s mark. . . .

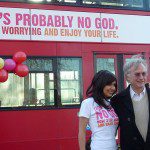

Catholicism has been replaced by a narcissistic and individualistic paganism whose elements are chosen like dishes at a buffet and include a vague, almost contentless and undemanding spiritualism, combined with sexual hedonism and a liberal social doxa. . . .

Very few children were given Muslim names in 1970; by 2016, Muslim names accounted for 18 percent, and the share is bound to increase.