(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976), who earned his doctorate in physics at the University of Munich in 1923 and his Dr. Phil. Habil. at the University of Göttingen in 1924, went on to serve as a professor of physics at the universities of Copenhagen, Leipzig, Berlin, Göttingen, and Munich. Along the way, in 1927, he formulated the famous principle of “indeterminacy” (Ungenauigkeit, or, as I myself might have been tempted to render it, “imprecision”), as he tended to call it, which has come to be known as the “Heisenberg uncertainty principle.” (In an endnote to the publication in which he introduced the principle, he also used the word Unsicherheit, or “uncertainty,” and that was the term that stuck in English.) For his role in the creation of quantum mechanics, Professor Heisenberg picked up a Nobel Prize in Physics five years later, in 1932.

For my own fiendish purposes, I’ve garnered three interesting quotations from him and one quotation about him that I’m inclined to share on a Sabbath evening:

“Der erste Trunk aus dem Becher der Naturwissenschaft macht atheistisch, aber auf dem Grund des Bechers wartet Gott.” (“The first gulp from the glass of natural sciences will turn you into an atheist, but at the bottom of the glass God is waiting for you.”) (Heisenberg, as cited in Hildebrand 1988, 10).

In a 1973 article entitled “Scientific and Religious Truth,” Heisenberg wrote that,

“In the history of science, ever since the famous trial of Galileo, it has repeatedly been claimed that scientific truth cannot be reconciled with the religious interpretation of the world. Although I am now convinced that scientific truth is unassailable in its own field, I have never found it possible to dismiss the content of religious thinking as simply part of an outmoded phase in the consciousness of mankind, a part we shall have to give up from now on. Thus in the course of my life I have repeatedly been compelled to ponder on the relationship of these two regions of thought, for I have never been able to doubt the reality of that to which they point.” (Heisenberg 1974, 213).

Perhaps because he had lived through the Nazi era, Heisenberg was concerned about the consequences if a transcendent source, basis, or ground of morality came to be denied:

“Where no guiding ideals are left to point the way, the scale of values disappears and with it the meaning of our deeds and sufferings, and at the end can lie only negation and despair. Religion is therefore the foundation of ethics, and ethics the presupposition of life.” (Heisenberg 1974, 219).

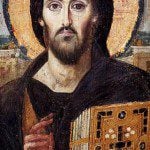

In an autobiographical article that was published in the journal Truth, Henry Margenau (who was, at the time, Professor Emeritus of Physics and Natural Philosophy at Yale University) wrote: “I have said nothing about the years between 1936 and 1950. There were, however, a few experiences I cannot forget. One was my first meeting with Heisenberg, who came to America soon after the end of the Second World War. Our conversation was intimate and he impressed me by his deep religious conviction. He was a true Christian in every sense of that word.” (Margenau 1985, Vol. 1).

Posted from Park City, Utah