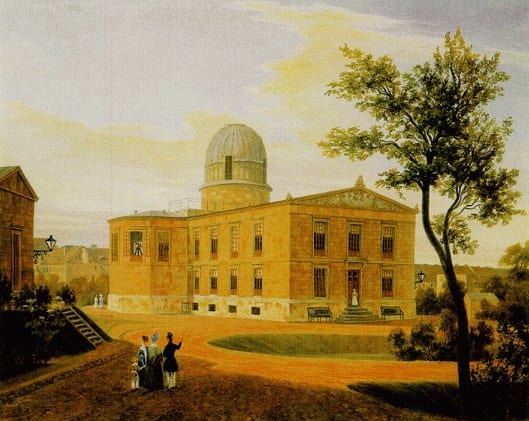

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Yesterday, in a post entitled “Day breaks over Mercury in a white heat,” I quoted a passage from Dava Sobel, The Planets (New York: Penguin, 2006), 41, rxplaining how the “discovery” of the planet Neptune by means of calculations and predictions based on “perturbed” behavior of other astronomical objects took place a full year or so before Neptune itself was spotted through a telescope. And I commented that discovery by inference, as it might be termed, is fairly common in the sciences, and perhaps particularly so in astronomy.

The scientist who postulated the existence of Neptune using only mathematics — “the man who discovered a planet with the point of his pen,” as one contemporary physicist apparently called him — was Urbain Le Verrier (1811-1877), the longtime director of the Observatoire de Paris. On 18 September 1846, he wrote a letter containing his prediction to Johann Galle of the Berliner Sternwarte (the Berlin Observatory). The letter arrived in Berlin five days later and, that very evening, 23 September 1846, Galle and Heinrich d’Arrest found Neptune within 1° of the location that Le Verrier had predicted.

The discovery made Le Verrier justly famous; his is one of the seventy-two names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

But, of course, such inferences can also go wrong, or point in the wrong direction. Ms. Sobel discusses one such case — largely forgotten today, I think — immediately following her brief remarks on Neptune. And this story, too, involves Urbain Le Verrier.

After his triumph regarding Neptune, Le Verrier turned his attention to observations of the planet Mercury. Through years of careful monitoring, he noticed that the precession of Mercury’s orbit around the Sun — that is, the wobbling of the axis of its rotation — could not be entirely explained by Newtonian mechanics as resulting from the gravity of the planets already known. This was exactly the same sort of reasoning that had led him to postulate an as-yet undiscovered planet, Neptune, that was impacting the orbit of Uranus.

Attempting to account for the observed anomaly in Mercury’s behavior, Le Verrier suggested that yet another planet might exist that orbited the Sun even closer than Mercury.

He also proposed other possible explanations, including a slight oblateness or flattening of the Sun and, alternatively, a group of smaller “corpuscules, or what we today might term “planetoids” or “planetesimals.”

But it was the notion of a single unobserved planet that seems to have caught people’s attention. That planet was soon dubbed “Vulcan,” and the search was on. But it didn’t go as well as the quest for Neptune. Nobody could find Vulcan. “Mercury was the god of thieves,” quipped the French astronomer Camille Flammarion after he and others had spent ten years searching for Vulcan without success. “His companion steals away like an anonymous assassin.” (Cited at Sobel, 42.)

But many astronomers were still looking for the planet as late as 1915 — Le Verrier’s perception of an anomaly in Mercury’s behavior was correct, and demanded explanation — when Albert Einstein informed the Prussian Academy of Sciences that Newton’s mechanics would actually break down under intense gravitational force. In the immediate vicinity of the Sun, he predicted, space itself would be warped. Thus, every time Mercury came closest — that is, at its “perihelion” — it would speed up more than Newton had predicted.

“Vulcan fell from the sky like Icarus in the wake of Einstein’s pronouncements,” comments Sobel (43).

“Can you imagine my joy,” Einstein asked a friend in a letter, “that the equations of the perihelion movement of Mercury prove correct? I was speechless for several days with excitement.”

So, here again, theory guided (or corrected) observation.