Notes from Dava Sobel, The Planets (New York: Penguin, 2006):

“I know that I am mortal by nature, and ephemeral,” says an epigraph opening Ptolemy’s great astronomical treatise, the Almagest, “but when I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies I no longer touch earth with my feet: I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia, food of the gods.” (33-34)

There is an awe — and, for very many, a sense of the divine — that naturally attends contemplation of the vastness, grandeur, and orderliness of the cosmos. Clearly, Ptolemy felt it.

***

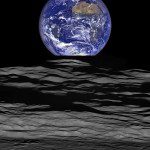

When I was growing up, it was often stressed that Earth is an ordinary, unremarkable planet orbiting an unremarkable star. Nothing out of the ordinary. Nothing unusual.

But Earth is unusual. Consider, for instance, this alternative:

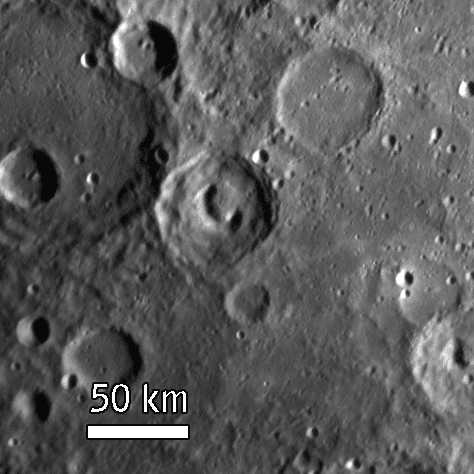

Day breaks over Mercury in a white heat. The planet has no mitigating atmosphere to bend early morning’s light into the rosy-fingered dawn of Homer’s song. The nearby Sun lurches into the black sky and looms enormous there, nearly triple the diameter of the familiar orb we see from Earth. Absent any aegis of air to spread out and hold in solar heat, some regions of Mercury get hot enough to melt metals in daylight, then chill to hundreds of degrees below freezing at night. Although the planet Venus actually grows hotter overall because of its thick blanket of atmospheric gases, and Pluto stays altogether colder on account of its distance from the Sun, no greater extremes of temperature coexist anywhere in the Solar System. . . . The planet experiences no real seasons, since it stands erect instead of leaning on a tilted axis the way Earth does. (35-36)

***

It’s important to understand that, in science, the existence of previously unknown entities is often indirectly inferred from their effects, not directly observed. Here’s an instance — one among very many that could be cited, perhaps especially from astronomy — of what I say:

the force of gravity, introduced by Sir Isaac Newton in 1687 in his book Principia Mathematica. Newton’s calculus and the universal law of gravitation seemed to give astronomers control over the very heavens. The position of any celestial body could now be computed correctly for any hour of any day, and if observed motions differed from predicted motions, then the heavens might be coerced to yield up a new planet to account for the discrepancy. This is how Neptune came to be “discovered” with paper and pencil in 1845, a full year before anyone located the distant body through a telescope. (41)