I published the following column in the 14 November issue of the Deseret News:

As we in the United States approach the national Thanksgiving holiday for 2019, it’s appropriate to consider things for which we should express our gratitude. Obviously, of course, there’s the good food that many of us will be eating. There are the family members with whom many of us will be gathering to share it.

However, there is much, much more. Indeed, our reasons for gratitude are virtually infinite. Here, let me suggest one vital factor in our lives that we almost always take for granted:

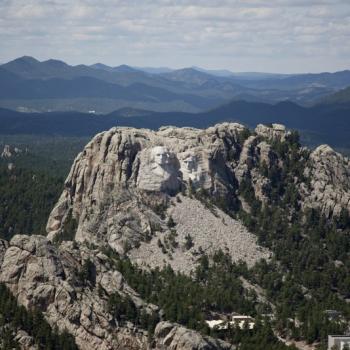

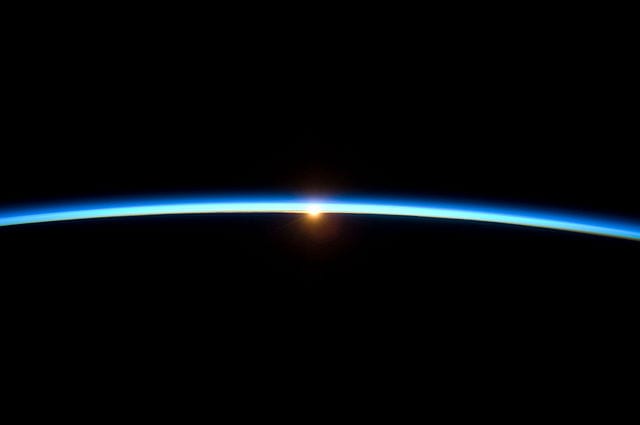

The phrase “thin blue line” is sometimes used to refer to the role of the police in society, who hold chaos at bay and thus permit order and civilization to flourish. The term could perhaps be used even more appropriately to describe the function of our terrestrial atmosphere, which allows not only civilization and order but sheer physical survival.

Our atmosphere as it exists today derives (as our oceans also do) from the “degassing” of the primitive semi-molten earth, supplemented by later additions belched up from volcanoes and emitted by hot springs.

The atmosphere of early geologic times was composed of such gases as hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, water vapor and various forms of hydrogen chloride. We couldn’t have survived those conditions. However, the lighter gases (e.g., hydrogen and helium) escaped toward space. Five hundred miles above the Earth, our “atmosphere,” if it can still be called that, is composed of 50% helium and 50% hydrogen.

Somewhat later in our planet’s history, living organisms developed that were capable of photosynthesis. They provided the oxygen that then permitted animal respiration and eventually the colonization of land, as well as providing the famous ozone layer that shields Earth (and us) from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation.

Evidence for this sequence of atmospheric development can be found, to some degree at least, in Precambrian rocks and a few fossils, which show a transition from a largely oxygen-free environment to what we might term a free-oxygen environment.

Our terrestrial atmosphere is an exceedingly thin envelope surrounding Earth. Perhaps somewhat more than 99% of our planet’s air exists within a region no higher than approximately 18 miles above sea level. Earth’s radius — the distance from its center to its surface or circumference — somewhat less than 4,000 miles, which means that the thickness of that oxygenated region of our atmosphere is a bit less than 0.5% of Earth’s radius.

But oxygen isn’t evenly distributed even within that thin envelope. Denser and, thus, heavier gases such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitrogen and water vapor hang low in the current atmosphere, mostly within about 3 miles of the planet’s surface. That thin band is equivalent to approximately 0.00075 of Earth’s radius, well under one ten-thousandth. Its outer edge is not far above our heads.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I followed those thoughts up on 28 November 2019 with the column immediately below:

Two weeks ago, I argued that we should be grateful for Earth’s atmosphere and the air we breathe (see “The miracle of Earth’s atmosphere design and the air we breathe” published Nov. 14, on deseret.com). Today, still in the Thanksgiving spirit, I suggest gratitude for the dirt beneath our feet.

The internal structure of our planet is a series of concentric spheres. A solid metallic “inner core” is surrounded by a liquid “outer core.” The “outer core” is, in turn, contained within Earth’s viscous “mantle.” And then, finally, we reach the solid “outer crust,” pretty much the planet of our daily experience.

Whereas Earth’s average radius is 3,958.8 miles (6,378 kilometers), the thickness of Earth’s crust ranges from about 43 miles (70 kilometers) beneath continental mountains to less than 5 miles (8 kilometers) beneath the oceans.

Rather like the film that forms on a cooling cup of hot chocolate, Earth’s crust “floats,” as it were, on the solid but soft and viscous or “plastic” mantle — much hotter and much more dense — located underneath. (This gives new meaning to the expression “solid earth” or “terra firma.”)

Obviously, we live atop the terrestrial crust. But even that crust is mostly inhospitable to life. On its surface, of course, things are (by definition) at air temperature. However, at the bottom of the world’s deepest mine, 2.4 miles down in South Africa’s TauTona, the ambient air temperature is 131 Fahrenheit (55 Celsius), and the temperature of rock surfaces is 140 F (60 C). Without artificial air conditioning, that air temperature alone would soon kill the miners. So the lowest humanly habitable depth on our planet is generously reckoned as about 2 miles down into the crust.

Deeper crustal temperatures reach approximately 1,600 F, or about 870 C. To put this in perspective, 350 F will bake bread. At 1,600 F, rocks begin to melt. Immediately beneath the crust is the solid but plastic mantle, where temperatures reach as high as 7.250 F (4,000 C).

Moreover, as my previous column noted, humans cannot usually function very well without supplemental oxygen beyond roughly 3 miles above sea level. Which means that we can only live in a thin region, roughly 5 miles thick, within the combined area of Earth’s nearly 3,960-mile radius and its surrounding 500 miles of atmosphere.

That’s a stunningly narrow range. Humans can survive in only 5/4460 (or 0.00112108) — slightly more than a tenth of 1% — of the vertical portion of Earth’s combined mass and ambient atmosphere.

The loose, upper, “weathered” layer of Earth’s crust is called “soil.” It’s tempting to dismiss soil as mere “dirt.” If something or someplace is “dirty,” we want to clean it, to get rid of the dirt. But life on Earth would be impossible without soil. For example, it helps to filter and clean our water, plays a vital role in cycling nutrients (e.g., the carbon and nitrogen cycles), and releases important gases such as carbon dioxide into our atmosphere. Very obviously, most plants require soil in which to grow. They anchor themselves into the ground with their roots and thereby extract nutrients from it — and animal life (including human life) clearly depends upon such plants.

Soil is not only vital to life. It teems with life, itself. A teaspoon of good soil, for example, will commonly contain several hundred million bacteria. Moreover, a typical acre of good cropland will serve as the home to more than a million earthworms. And, of course, many animals, fungi and bacteria rely on soil as a place in which to live.

However, the primary layer where plants and other organisms live is the topsoil, which is usually only 5-10 inches thick where it exists at all. The formation of just an inch of topsoil can require up to 1,000 years. Below the topsoil is the subsoil, which is made up primarily of clay, iron and organic matter. Below the subsoil is the so-called “parent material,” mostly large rocks that have not yet been completely broken down — so called because the topsoil and subsoil develop from it. And beneath the “parent material” is bedrock, a large mass of solid rock located several feet below the surface.

So human life depends upon 5-10 inches of dirt on the surface of a planet that’s nearly 8,000 miles in diameter.