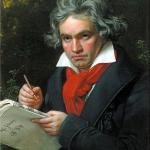

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

I’ve long felt that American Thanksgiving tends to be a somewhat forlorn and relatively neglected holiday. Falling between the fun of the costumes and candies and houses of horror associated with the entirely desacralized holiday of Halloween and the weeks of carols and festivities (and unrelenting commercialism) of the partially desacralized Christmas, it tends to be reduced to something of a poor relation — a day, merely, of family get-togethers and good traditional foods. Both of which, I hasten to say, are good things. But gratitude and actual thanks-giving can sometimes be lost among the bustle and the travel and the meal preparation. And I’m not just pointing the finger of reproach at others. I myself am often guilty of precisely such neglect.

In an attempt to improve things just a bit — at least in my own case — I intend to repost here some of the columns that I’ve written for Thanksgiving in past years, accompanied by hymns that are appropriate to the holiday.

The first of the hymns that I’ve chosen was probably inspired by Psalm 23:6 and Psalm 150:

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Here is a piece that I published with my late friend Bill Hamblin back in 2013:

American traditions of Thanksgiving are generally associated with Puritan harvest feasts in early colonial times, and particularly with the one in October 1621, when Chief Massasoit and about 90 other Native American men joined slightly more than 50 European immigrants at Plymouth Colony, in today’s Massachusetts, for a communal meal.

Abraham Lincoln’s formal proclamation of a late-November “Day of Thanksgiving and Praise” came just 150 years ago, in 1863. However, religious festivals of thanksgiving associated with the agricultural cycle, thanking God for a bounteous harvest — essential to life through the winter — are much more ancient and universal, and can be found in most religious traditions of the world.

In ancient agrarian societies, where survival ultimately depended on rain and on the fertility cycles of local plants and animals, a failed harvest could swiftly bring widespread disaster and death. Accordingly, a bountiful harvest was received with gratitude.

The sacrifices and festivals of ancient Israel were likewise fundamentally linked to the annual seasons of planting and reaping. One of their sacrifices was actually called the “thanksgiving” (Hebrew “todah”). As described in Leviticus 7:11-15, the thanksgiving offering was an entire meal, including fried cakes, bread and meat. Furthermore, it was commanded that “the flesh of the sacrifice of the peace offerings for thanksgiving shall be eaten the same day that it is offered.” That is, the ancient Israelite thanksgiving sacrifice was a sacred feast, a meal in which the food offerings were symbolically shared with God but were literally eaten by the sacrificer. In ancient Israel, such a “holiday feast” — as we now describe it — was actually a “holy-day feast.”

One of the fundamental psalms sung by the Levite choir each day at the temple was “O give thanks unto the Lord, for he is good, and his mercy endures forever” (Psalms 106, 107, 118, 136, 138; 1 Chronicles 16:7, 34, 23:30; 2 Chronicles 5:13, 7:6; Nehemiah 12:8). One could enter the Israelite temple only if one “entered the gates with thanksgiving” (Psalms 100:4, 95:2). Psalm 50 describes the characteristics of the “thanksgiving sacrifice” (50:15): “he who offers thanksgiving (Hebrew “todah”) glorifies me” (50:23; cf. Psalm 116:17).

When Jeremiah prophesied of the future restoration of Jerusalem and its temple, which was to come following the Babylonian captivity, he predicted that the returning Jews would “bring thank offerings to the house of the Lord” (Jeremiah 17:26) and singing “songs of thanksgiving” (Jeremiah 30:19). Jeremiah likewise prophesied that in Jerusalem should again be heard “the voice of joy and the voice of gladness, the voice of the bridegroom and the voice of the bride . . . as they bring the thanksgiving sacrifice (Hebrew “todah”) into the House of the Lord” (Jeremiah 33:11).

In the New Testament, Jesus Christ is twice described as giving thanks in the context of a sacred meal. At the feeding of the 5,000, he took the loaves and fish and, “having given thanks, he broke them and gave them to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds” (Matthew 15:36; Mark 8:6; John 6:11).

In the old Israelite thanksgiving sacrifice, the people were to bring food to the temple and give it to the priests, who would then offer it to God. Now, in a paradoxical reversal of the old order, Christ, as God incarnate, brings the food, offers thanks and gives it to his apostle-priests who then offer it to the people. The old order of the thanksgiving offering is thus reversed.

The same reversal of roles is found at the Last Supper, where, at the Passover dinner, Jesus gives thanks and shares a sacred meal with his apostles (Matthew 26:37; Mark 14:23; Luke 22:17, 19; 1 Corinthians 11:24). Christ’s atoning sacrifice has thus become a “thanksgiving offering.”

Although in Latter-day Saint tradition we tend to call our commemoration of the Last Supper the “sacrament,” in ancient Christianity it was referred to as the Eucharist — the “thanksgiving.” This is because Christ is described as having “given thanks” at the Last Supper — in Greek, “eucharistesas.” (Still today, the modern Greek equivalent of “thank you” is “efkharisto.”) Thus, for Latter-day Saint Christians, the sacrament is our commemoration of the archetypal thanksgiving sacrifice and meal of ancient Israel, of which our modern Thanksgiving holiday is only a pale shadow.

Appropriately, too, for many Americans, Thanksgiving kicks off the serious holiday season that culminates in Christmas, which recalls God’s greatest gift to us, his Son.

My wife and I participated in a small private screening of Six Days in August up in Salt Lake City yesterday evening. It was the first time that I had seen the movie in several weeks, and I was reminded yet again of how good and solid a film it is. I’m proud of what we were able to accomplish, and I look forward now to seeing the remainder of the project take shape.

(Wikimedia Commons photo by Scott Catron)

But it’s crying time again: I’m going to leave you. You can see that Hitchens File look in my eyes. You can tell by the horrors you see coming that it won’t be long before it’s crying time. So here are a few of my latest gleanings from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™:

- “Church’s Role in Improving Global Nutrition Highlighted at International Conference: Church presents work at World Food Prize Borlaug International Dialogue, an annual conference in Des Moines, Iowa”

- “BYU Students and Grads Are Saving Newborns and COVID Victims, One Breath at a Time”

- “Giving Machines Spread Christmas Cheer at North Pole”