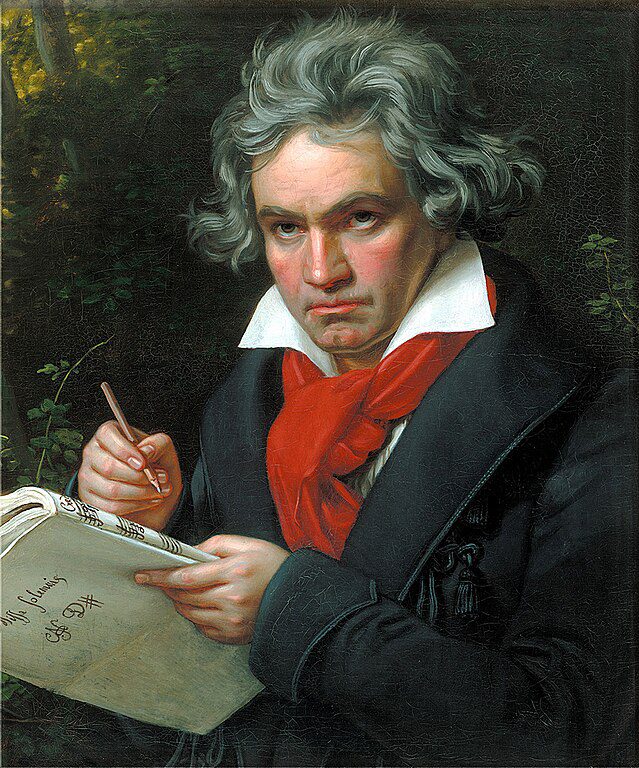

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Yesterday evening, we met friends for dinner at Maria’s Mexican Grill in South Jordan — this was our first time there, by the way, and, for whatever it may be worth, I thought my food was unusually good — and then we headed up together to Symphony Hall in Salt Lake City. We arrived early, for a discussion of that night’s program with the Symphony’s Assistant Conductor, Jessica Rivero Altarriba. As a special treat, though, she introduced the Utah Symphony’s just-announced Music Director Designate, Markus Poschner, and conducted a very brief interview with him. He is very personable, and his English is excellent. As it happened, he was already scheduled as the guest conductor for last night.

The concert fell into two parts. The first was Benjamin Britten’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 13, with Benjamin Grosvenor as pianist. The second was Beethoven’s great Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica.”

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) wrote his so-called “Heiligenstadt Testament” — despite the grand title by which it’s come to be known, it was simply a letter to his brothers Karl and Johann — in 1802. In it, he explained his increasing withdrawal from the world on account of growing deafness. “Ah,” he wrote to them, “how can I admit to an infirmity in the one sense that ought to be more perfect in me than in others?” It’s a heartbreaking letter, and a heartbreaking situation. Only slightly more than a year later, though, he began work on his Third Symphony, which proved to be revolutionary not only for him but, really, in the history of western music altogether. (And the Fifth, the Sixth, the Seventh, and the glorious Ninth — my personal favorites — were yet to come.)

Famously, Beethoven originally dedicated the Third Symphony to Napoleon, idealistically imagining that Bonaparte was intending to follow through on the ideals of the French Revolution: Liberté, égalité, fraternité. But then, when Napoleon declared himself Emperor of France, Beethoven was disillusioned and angrily repudiated his dedication.

Thinking of Beethoven’s deeply tragic biography once again, however, I feel it appropriate to share here a column that I wrote for the Deseret News back in 2012. I hope that you won’t mind:

Human potential is never fully realized in mortality. Too often, in fact, it’s scarcely realized at all.

Consider Ludwig van Beethoven, certainly among the foremost composers of all time, perhaps indeed the very greatest.

A prodigy born in 1770 to a commonplace court musician and to a chambermaid who died of tuberculosis when he was 16, he began to perform professionally at the age of 10. Thereafter, he received no further education except in music.

His health was terrible almost from the start. Although some have suspected that he brought his illnesses on himself through alcoholism and immorality, this seems to be false. He already suffered from chronic colic and diarrhea, and from frequent fevers and septic abscesses, by his 21st birthday.

When he was only 27, he began to go deaf. Experts now think that he suffered from otosclerosis, an abnormal sponge-like bone growth in the middle ear whose cause is unknown (though it may be genetically transmitted). This growth prevents the ear — and usually both ears — from vibrating in response to sound waves, which is essential to being able to hear. Even today, the disease is progressive and incurable.

Well before his 30th birthday, Beethoven suffered from incessant ringing and whistling in his ears, and, especially in winter, from terrible earaches and headaches. By 1805, when he was in his mid-30s, he could scarcely hear wind instruments. Yet noises caused him pain; he often stuffed his ears with cotton wool, and, in 1809, he covered his head with cushions in an attempt to escape the horrific roar of Napoleon’s cannons bombarding Vienna.

By 1812, his visitors had to shout to be understood. He destroyed piano after piano, pounding upon the keys out of his desperation to hear. Five years later — when he was still only about 47 — he was completely deaf and could no longer hear music at all.

His great Ninth Symphony premiered on May 7, 1824, in Vienna. He was there, standing near the conductor, but he never heard it. (You may have, but he never did. Think about that.) Reportedly, several in the orchestra wept as they played. Afterward, the contralto soloist turned him around to see the passionate applause of the audience who, seized by emotion, applauded all the louder and more visibly.

Beethoven died less than three years later, at 57, apparently from complications of jaundice, which he had contracted roughly seven years before. The autopsy revealed a ravaged, worn-out liver, and modern scholars suspect that he may have suffered for many years from an immunopathic disease called systemic lupus erythematosus, which begins in early adulthood — at about the same time, in other words, that his otosclerosis began to manifest itself — and, though it may come and go for a while, eventually becomes chronic. Its symptoms include not only liver disease but rashes, redness in the face, rheumatism, and emotional instability.

And Beethoven certainly had emotional issues. Ravaged by constant stomach pain, frustrated by his uniquely tragic combination of musical genius and deafness, he was quarrelsome, suspicious, rude, commonly in a state of rage. And, thus, he was desperately lonely. His living quarters were disorderly and often filthy. He was perpetually in money troubles — partly, perhaps, because he lacked basic skills in arithmetic. He never married; he couldn’t even keep servants. “Oh, God,” he begged in his journal, “may I find her at last, the woman who may strengthen me in virtue, who is permitted to be mine.” But he never did.

It’s impossible not to wonder what this musical titan might have accomplished had he been healthy, had he lived longer, and had he been able to hear. It’s impossible to believe that he achieved his full potential as either a composer or, even, a human being.

Beethoven’s heart-rending biography — and many millions like his, or worse — is no argument for a future life. Perhaps, a skeptic might say, there’s no purpose to the cosmos. That’s just the way it is. We live briefly, we die meaninglessly, and then our little candle is extinguished — as all light and life ultimately will be extinguished in the vast heat-death of the universe.

But it should certainly cause us to hope for a future in which wounds are healed, deep yearnings satisfied, and human potential fully realized.

Fortunately, in the Resurrection of Christ and the Restoration of the Gospel there is a firm foundation for that hope.