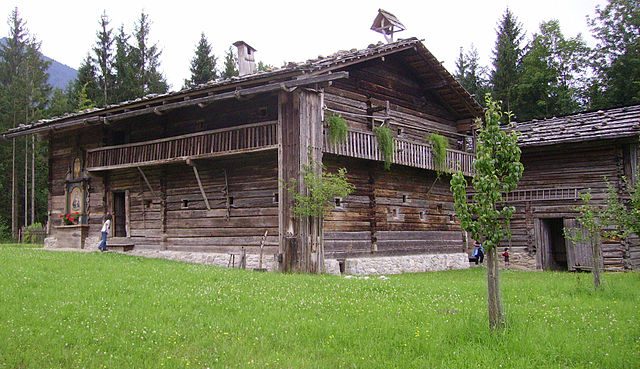

My wife and I went out with Scott Gordon and his wife to the Salzburger Freilichtmuseum — the open-air museum — in Großgmain, not too far outside of Salzburg. We walked around most of it, looking at the collection of traditional regional buildings (e.g., farmhouses, barns, a small chapel, and the like) that have been gathered there. At least one of those that we visited dates back to the mid-1500s. They remind me very much of the older mountain chalets and farmhouses that I saw every day in rural portions of the Berner Oberland in Switzerland, some of which were of approximately the same era.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

A few days ago, I posted an entry here under the title of “Christopher Hitchens and the Great Composers” in which I examined whether the late Mr. Hitchens’s claim that “religion poisons everything” holds true for, say, classical music. (Hint: I believe that it does not.) That was a first installment. Here is a second:

Like Bach, Franz Joseph Haydn (d. 1809) began his musical scores with In Nomine Jesu and ended them with either Laus Deo (“Praise God”) or Soli Deo Gloria. He rose early and always prayed before he commenced his composing. He would sit at his clavier and search for a musical idea. “If it soon comes without much difficulty,” he said, “it expands. But if it does not make progress, I try to find out if I have erred in some way or other, thereby forfeiting grace; and I pray for mercy until I feel that I am forgiven.”[1] In this manner, he eventually produced such works as the oratorio The Creation, The Lord Nelson Mass, the Mass in Time of War, and The Seven Last Words of Christ.[2]

“It sometimes seems to me,” remarked the great composer of art songs (Lieder) Franz Schubert (d. 1828), “as if I did not belong to this world at all.”[3] He criticized the kind of music that “rouses [people] to scornful laughter instead of lifting up their thoughts to God.”[4] In his Ave Maria and in his seven masses (including the marvelous Mass No. 2 in Gand the Mass No. 6 in E-flat Major), he made every effort to lift minds heavenward.

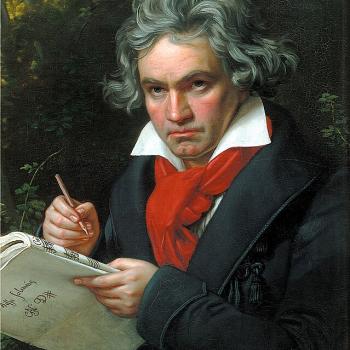

“It was not a fortuitous meeting of the chordal atoms that made the world,” said Ludwig van Beethoven (d. 1829). “If order and beauty are reflected in the constitution of the universe, then there is a God.”[5] Along with all of his other works, he produced such deeply religious choral music as the Missa Solemnis, the Mass in C, and Christ on the Mount of Olives.

Much like Bach and Haydn, Felix Mendelssohn (d. 1849) often included prayers in his musical manuscripts. Lass es gelingen Gott (“Let it succeed, God!”), he would write, or Hilf du mit (“Help thou along!”). Among his works are the oratorios Elijah and St. Paul, as well as choral settings of the biblical Psalms and Hymns of Praise.[6]

Richard Wagner (d. 1883) worked for months on the libretto for something he called Jesus of Nazareth but never finished, composed a huge work for orchestra and three choruses entitled Love Feast of the Twelve Apostles, and worked clearly Christian themes into many of his great music dramas, including Tannhäuser, Lohengren, and, most obviously, Parzival.

Franz Liszt (d. 1886) was both an incorrigible womanizer and a fervently devout Christian, who, in his fifties, finally entered the Third Order of St. Francis of Assisi in Rome. He was, says his biographer Eleanor Perenzi, “probably the nineteenth century’s greatest composer of religious music.”[7] He himself declared that music’s purpose was “to ennoble, to comfort, to purify man, to bless and praise God.”[8] His piano pieces included the Harmonies poetiques et religieuses and the Annees de pelerinage [“Years of Pilgrimage”]. He set numerous psalms to music, created a massive oratorio entitled Christus, drew on Gregorian chant for his Via Crucis (“Way of the Cross”), and wrote regarding one of his masses that he had “prayed” rather than “composed” it.[9]

Charles Gounod (d. 1893) was seriously tempted by the priesthood at various points in his early life. It is scarcely surprising that he composed several masses, including his famous Messe Solennelle and a Requiem. He also composed oratorios such as Redemption and Mors et Vita (“Death and Life”) and religious songs such as Nazareth, and combined his love for theology and opera in his great opera Faust. His most performed work, however, is unquestionably his Ave Maria.

Cesar Franck (d. 1890), organist at the church of Sainte-Clotilde in Paris for over thirty years, “did not play in order to be heard,” said his student and fellow composer Vincent D’Indy, “but to do his best for God and his conscience’ sake.”[10] Similar motives impelled him to write oratorios on The Tower of Babel and The Beatitudes, choral music on Ruth and Rebecca, and the cantata Redemption. “Franck’s purpose in writing sacred cantatas was . . . not so much to comfort the believer as to arouse the potential convert.”[11]

[1] Ibid., 39.

[2] Ibid., 37-43.

[3] Alfred Einstein, Schubert, a Musical Portrait (New York: Oxford University Press, 1951), 312-313.

[4] Otto Erich Deutsch, ed., Franz Schubert’s Letters and Other Writings (London: Faber & Gwyer, Ltd., 1928), 29.

[5] Friedrich Kerst, Beethoven, the Man and the Artist, As Revealed in His Own Words (New York: Dover, 1964), 104.

[6] Kavanaugh, Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers, 75-81.

[7] Ibid., 96.

[8] Lina Ramann, Franz Liszt, Artist and Man (London: W.H. Allen, 1882), 384.

[9] Kavanaugh, Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers, 96.

[10] Vincent d’Indy, Cesar Frank –Some Personal Reminiscences (New York: Dover, 1965), 44.

[11] Lawrence Davies, Cesar Franck and His Circle (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1970), 97.

[to be continued]

In posting this material, I’m drawing not just from the justly world-famous Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™ but, very specifically, from a much larger and as-yet unpublished manuscript that I wrote up (but never quite completed) a number of years ago.

Posted from Salzburg, Austria