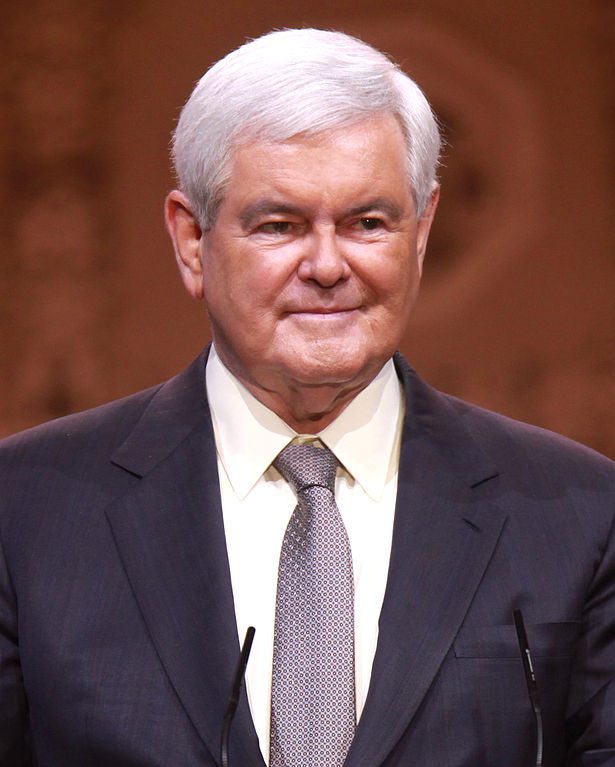

Newt Gingrich is no longer a presidential candidate, of course. And, Donald Trump having sucked all of the oxygen out of the Republican room, he will never be again.

But this response that I wrote to something that he said years ago when he was a candidate — a response that I published in the Deseret News on 14 December 2011 — may still be relevant, since the issue arises from time to time:

Newt Gingrich presents himself as a thoughtful statesman distinguished from his rivals by his deep historical learning.

“Remember, there was no Palestine as a state,” Gingrich told the Jewish Channel last week. “It was part of the Ottoman Empire. And I think that we’ve had an invented Palestinian people, who are in fact Arabs and were historically part of the Arab community. And they had a chance to go many places.”

Challenged during Saturday’s Republican debate, Gingrich insisted that his comments were “factually correct” and “historically true,” declaring that “‘Palestinian’ did not become a common term until after 1977.”

Predictably, Palestinians and liberals have objected to his remarks. And, also predictably, many conservatives, staunch friends of Israel, have applauded what he himself has called his “courage to tell the truth.”

There are, I think, relatively few politically conservative American Arabists. But I’m one, and I reject Mr. Gingrich’s declaration that Palestinians are merely an “invented people.” His claim is not only needlessly provocative and inflammatory (in a region that scarcely needs inflaming) but false.

First of all, Arabs aren’t fungible, as Gingrich implies. That is, they aren’t interchangeable in the way one bushel of corn or bottle of Coke can easily be substituted for another. Morocco, Lebanon, Kuwait, Egypt, Yemen, Iraq—each differs from the others in cuisine, dialect, traditions, social structure, and political practices. There is no monolithic, undifferentiated “Arab community.”

Few Americans would be comforted, if the United States were conquered by foreign invaders, to be told that they could just “go home” to Johannesburg, Brisbane, or London. Americans aren’t New Zealanders, nor are they Scots. Likewise, though they’re all Arabs, Palestinians aren’t Saudis, who aren’t Algerians, who aren’t Lebanese. They have separate histories and cultures.

“Modern Standard Arabic” is taught in schools and is the language of formal speech and almost all publishing. But the dialects spoken on Arab streets and in Arab homes—unlike Brooklyn or Mississippi accents, and unlike Australian, North American, and British English—constitute virtually separate languages. Moroccan Arabic, for instance, is almost incomprehensible to Iraqis (and, for that matter, to Egyptians and Palestinians). A quick on-line search will find many published books on the distinct grammars and vocabularies of Egyptian Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, Levantine Arabic, and Iraqi Arabic.

Second, while it’s true that there was no Palestinian state under the Ottoman Empire, which officially fell only in late 1923, that signifies little. There was also no truly independent Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, or Jordan. The Ottoman Empire wasn’t particularly supportive of nationalist sentiments among its subjects.

Arab nationalism emerged in the late nineteenth century, paralleling the Ottomans’ long, slow decline. (The term “nationalism” itself had been invented in Europe, where nationalistic movements first arose, only in the late eighteenth century.) It was part of the same broad trend that, in Europe, resulted in the unification of Italy and the creation of Germany (both in 1871) and inspired the Czechs Smetana (b. 1824) and Dvorak (b. 1841)) and the Norwegian Grieg (b. 1843) and the Finn Sibelius (b. 1865) to base great classical compositions upon the folk songs and tales of their homelands. (Early Arab nationalism from the time of the First World War is brilliantly depicted in David Lean’s 1962 film “Lawrence of Arabia.”) Zionism itself—Jewish nationalism—can be said to have been born with the publication of Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State” in 1896.

Third, it’s true that a specifically Palestinian identity is a relatively recent development. But it’s false to suggest that this only became current “after 1977.”

The name “Palestine” stems from the ancient Philistines, who formed an independent state alongside the ancient biblical kingdom of Israel. Greeks and Romans regularly used the term, and the Romans officially gave the name “Palestine” to the province of Judea around 135 C.E., after the second Jewish revolt. The name survived throughout the Middle Ages under both Arab and Ottoman rulers, who routinely referred to Palestine’s residents as “Palestinians.” Medieval and early modern Jewish writers also often called the Holy Land “Palestine.”

A sense of Palestinian identity is clearly evident in the Arab-organized Syrian-Palestinian Congress of 1921 and was fostered by the establishment, under the League of Nations, of the “British Mandate for Palestine” in 1922. In 1927, more than twenty years before the founding of Israel, Palestinian coins were issued bearing the name “Palestine.” Even the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was created in 1964, thirteen years before Newt Gingrich’s “1977.”

Fourth, it’s false to say that Palestinians were “invented” as propaganda. Palestinians have had a distinct and quite depressing history of their own for at least a century. It would be inexplicably bizarre if they had failed to develop a separate sense of identity. Moreover, their Arabic dialect is recognizably unique.

Fifth, it’s misleading to suggest that Palestinian identity is merely a tool used by “the Arabs” to manipulate the West. Arabs themselves, though universally sympathetic to Palestinian grievances, perceive Palestinians as distinct. In fact, though this is seldom openly discussed, displaced Palestinians living in their “diaspora” have often been felt, and resented, as a foreign presence in the Gulf and elsewhere in the Arab world—including, even, in Jordan.

Newt Gingrich may or may not be a solid historian of America. With his dismissal of the Palestinians as an “invented people,” however, he hasn’t established his credibility on the Middle East. And Israel isn’t helped by bad history.