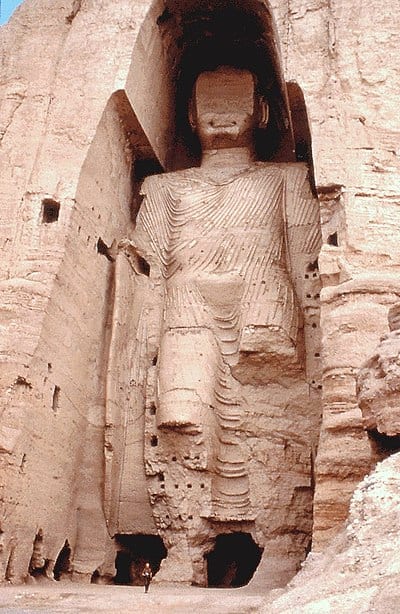

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

I published this column in the Provo Daily Herald on or around 5 March 2001:

Notwithstanding the international outcry that followed their announcement that they intended to destroy two massive ancient statues of the Buddha, the Taliban militia who control 90% of Afghanistan have apparently proceeded with the demolition. “It is not a big issue,” said Taliban minister of information and culture Mawlawi Qudratullah Jamal. “The statues are objects only made of mud or stone.”

The two statues – one roughly 120 feet high and the other 175 feet – were among the greatest surviving pieces of early Buddhist art. Carved into a sandstone cliff near the city of Bamiyan, about 90 miles west of the capital city of Kabul, the statues were at least 1500 years old. Previously, they had survived cannon fire from the soldiers of Genghis Khan in the early thirteenth century, an attack ordered by the Moghul emperor Aurangzeb in the seventeenth, and a damaging 1998 rocket-and-dynamite assault by the Taliban themselves.

The Taliban represent an extraordinarily rigid form of Islam. They imprison men who trim their beards in a fashion unlike that of the Prophet Muhammad. They refuse to allow the education of girls. They bar women from employment (or even, really, being seen) outside the home – and thus, by an edict disastrous in a very Third World country, have stripped nurseries, elementary schools, and hospitals of their principal staff. Even the Islamic Republic of Iran (scarcely a hotbed of feminism) has denounced them for their repression of women. The difference between the two Islamic factions can be neatly summarized as follows: For Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, anything not expressly forbidden to women by the Qur’an and authoritative Islamic tradition is permitted. By contrast, for the Afghani Taliban, anything that the Qur’an and tradition do not expressly permit to women is forbidden. As might easily be predicted, the two rules lead to very distinct social policies.

Afghanistan, once a crossroads of Europe, India, and China, is now, more than ever before, a backwater. The Soviet invasion of the 1970s and the Western military aid designed to counter it energized and equipped a fundamentalist Islamic movement among the legendarily fierce Afghan warriors. Seemingly, nobody foresaw the direction it has taken. The Taliban are recognized by only three countries (Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) – all of them Islamic – as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Now, however, even these three nations have expressed disapproval of the appalling plan to destroy the statues at Bamiyan.

But the destruction of images, and particularly of those associated with another religion, has an ancient pedigree and many precedents in the history of the three kindred faiths, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. One of the Ten Commandments given to Moses at Sinai declares, “You shall not make yourself a carved image of any likeness of anything in heaven above or on earth beneath or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them. For I, Yahweh your God, am a jealous God” (Exodus 20:4-5, New Jerusalem Bible). Similar prohibitions exist in Islam. And, although many commentators have emphasized the ban on worshiping such images – the forbidding of idolatry – some have taken the principle very literally, even banishing photography and representational art.

The conquering Israelites, for whom Canaanite religion was a long-standing temptation, destroyed temples and images of Canaanite gods that modern archaeologists would dearly love to possess. Triumphant Christians engaged in wholesale destruction of pagan shrines and idols wherever they found them. The temples of ancient Egypt still bear the marks of early Christian devotion: Reliefs and statues were mutilated on an impressive scale. In the eighth and ninth centuries, the bitter “iconoclastic controversy,” in which (perhaps under Muslim influence) factions of Greek Orthodox Christians contended with one another over the legitimacy of “icons” or devotional images obliterated innumerable works of art. So too, as part of the cultural upheaval that accompanied the European Reformation in the sixteenth century, a great deal of the decoration of northern Europe’s churches was destroyed. (The austere interior of Ulrich Zwingli’s great church in Zürich, the Grossmuenster, furnishes a particularly clear illustration of the Reformation’s effects in this regard.) Just a few years ago, citing the precedent of Moses and Joshua, an evangelist in Texas announced that he had destroyed several pieces of twelfth-century Japanese Buddhist art that a donor had given to him to support his ministry.

Culture minister Jamal expected no difficulty with the demolition of the Buddhas. “It is easier,” he remarked a few days ago, “to destroy than to build.” Depressing, but true.