Back on 23 June 2011, nearly a decade ago now, I published the following article in the Deseret News. I share it here again because I think it may have some relevance to our nation’s current woes:

For many years, I regarded Helaman 13:5-6 as an example of bad, repetitious prose in the Book of Mormon:

“And he said unto them: Behold, I, Samuel, a Lamanite, do speak the words of the Lord which he doth put into my heart; and behold he hath put it into my heart to say unto this people that the sword of justice hangeth over this people; and four hundred years pass not away save the sword of justice falleth upon this people.

“Yea, heavy destruction awaiteth this people, and it surely cometh unto this people, and nothing can save this people save it be repentance and faith on the Lord Jesus Christ, who surely shall come into the world, and shall suffer many things and shall be slain for his people.”

Repeating the phrase “this people” six times in two sentences was, I thought, boring, even embarrassing, and definitely very poor style.

Reading the passage aloud one day, however, I realized that I was wrong.

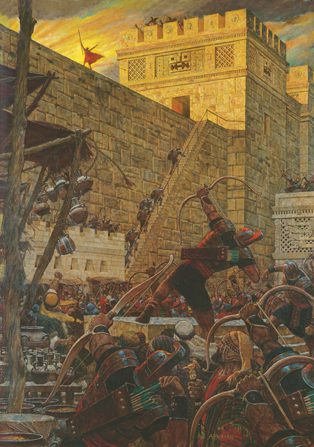

Samuel, who deliberately stresses that he’s “a Lamanite,” is speaking from the wall of the city of Zarahemla to a violently hostile Nephite audience. They’re wicked, but they’re also inclined to think themselves superior because of their lineage. (Samuel’s acute awareness of the ethnic issue is obvious at Helaman 14:10 and in Helaman 15:3-17.)

In the preceding chapter (Helaman 12:4-7), the prophet Mormon had inserted an editorial comment, drawing not only upon the materials he was editing but upon his own experience (see Mormon 3:9; 4:8): “O how foolish,” he exclaimed, “and how vain, and how evil, and devilish, and how quick to do iniquity, and how slow to do good, are the children of men. … Yea, how quick to be lifted up in pride; yea, how quick to boast.”

His own view? “O,” he exclaimed, reflecting on human resistance to God’s authority, “how great is the nothingness of the children of men; yea, even they are less than the dust of the earth.”

When I read aloud Samuel’s denunciation of the people of Zarahemla, I understood it. The repeated condemnations of “this people” were followed by a promise that the divine Savior would enter into our world in order to “suffer” and “be slain for HIS people.” Samuel was contrasting “this people” (the Nephites) from God’s people. He was telling his prideful audience that merely being Nephites would not save them. Being faithful to their covenants, and, thus, enrolled among the Lord’s covenant people was their only hope of salvation.

The passage’s repetitive drumbeat of “this people” was designed, I think, to emphasize the concluding “his people.” It’s rather like what music theorists call “resolution,” which is the move from a dissonant or unstable sound, either a single note or a chord, to a consonant or stable one. The irritating “this people” yields to the serene and comforting “his people.”

I learned from this little reading experience that it’s very helpful to read the scriptures aloud, to hear them with our ears as well as in our minds. It dawned on me, too, that the style of the Book of Mormon might be (and I now testify that it actually is) much more subtle and sophisticated than we often realize.

We need to be better readers. The Book of Mormon will amply repay the effort.

But I also realized that the Book of Mormon cautions us powerfully against racism and undue ethnic pride. And I’ve recognized since then that this seemingly modern theme is more common in the scriptures as a whole than we’ve often noticed.

Consider an example from the Old Testament:

During the fifth-fourth centuries before Christ, Ezra and Nehemiah and other Jewish exiles, returned from Babylonian captivity, were rebuilding Jerusalem. They were also purifying the rolls of the priests, expelling those with uncertain lineage or non-Israelite wives. (By New Testament times, Jews were altogether forbidden to eat or socialize with Gentiles.)

Some scholars believe that the book of Ruth was written (or, at least, finalized) during or just after this period, as a protest or caution against overemphasis on racial purity. Ruth, a Moabite woman — the Moabites were despised neighbors of Israel — converts to the religion of the Israelites, marries into Israel, and becomes the ancestor of the royal house of David and, thereby, of the Messiah himself.

“His people,” not “this people.”