(Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

The death of Herod the Great marked the end of the last period of stable Jewish rule in Palestine until, in the middle of the twentieth century, David Ben Gurion proclaimed the state of Israel. True, Herod had sons, but they proved unworthy and incompetent. Archelaus, to whom Herod left Judea, was deposed by the Romans in 6 A.D. For several decades afterwards, the province of Judea and its major city, Jerusalem, were ruled directly by a Roman procurator or imperial governor from his headquarters in Caesarea on the coast. (Pontius Pilate was one of these procurators.) It seems, however, that the Romans really didn’t want to rule Judea directly. In 37 A.D., they returned the province to the family of Herod the Great, appointing his grandson, Herod Agrippa, to rule the area. Agrippa appears to have been a competent ruler, but he died relatively young in 44 A.D., and the Romans saw themselves with no choice but to impose direct rule again. And that, effectively, was the end of any real possibility for Jewish self-government in Palestine.

But many Jews continued to hope for independence and self-rule, and there were many rebellions. The Zealots, for example, carried out street assassinations. The so-called Essenes, gathered on the barren shores above the Dead Sea, dreamed of apocalyptic violence and produced military training manuals such as the one entitled “The War of the Children of Light Against the Children of Darkness.” (It doesn’t take much imagination to realize which side they saw themselves on.) But these revolutionaries had little chance of success, and they were crushed every time the Romans could catch them. Rome must have been rather puzzled by Jewish dissatisfaction. Most Roman provinces prospered and were largely at peace. In fact the majority of the Jews were satisfied, if the truth were known. Rome was liberal and tolerant by ancient standards; its governors were usually competent, and its laws were just. The Romans’ image as something like ancient Nazis, standard in Hollywood movies for many years, is undeserved. But the Jews were different, and Judea was a constant source of trouble and torment for its Roman rulers.

In 66 A.D., the “Great Revolt” (as it’s known) of the Jews against Rome broke out in Caesarea. It started with a riot in which Greeks began to kill Jews while the Greek-speaking Roman garrison of the town stood by with its hands in its pockets. A massacre ensued, and the news spread to Jerusalem, where more riots broke out. The situation was made worse by the fact that the Roman occupation government, needing money, had decided (like Antiochus before them) to dip into the temple treasury. Radical Jewish nationalists saw this as their opportunity to throw the Romans out once and for all. They also turned their attention to the Jewish upper classes, to the Hellenizers, whom they equated with the evil Greeks and who had identified themselves so completely with Roman rule. (“We have no king but Caesar,” the chief priests had told Pilate when seeking Christ’s death.)[1] We know that the aristocratic rich were a target of the radicals because one of the radicals’ first acts, when trouble broke out in Jerusalem, was to seize and burn the temple archives, which housed all records of debts.

The rebels also attacked and massacred the Roman garrison in Jerusalem. Such an act, of course, couldn’t possibly go unpunished. The Roman legate in Syria, who bore overall responsibility for the entire region, thereupon gathered a large force and marched unsuccessfully on the city. At this, Rome itself took over. An enormous force of four Roman legions, under the command of a highly experienced general named Titus Flavius Vespasian, moving at a careful pace, cleared the coast, seized virtually every fortress held by Jewish forces, and pacified the countryside. It was a smooth, professional operation. And it was noticed by those who counted. In 69 A.D., Vespasian was chosen emperor of Rome, and he departed for Italy after leaving his son Titus, a future emperor himself, in charge of the army during the final phase of the campaign, which centered on the siege of Jerusalem.

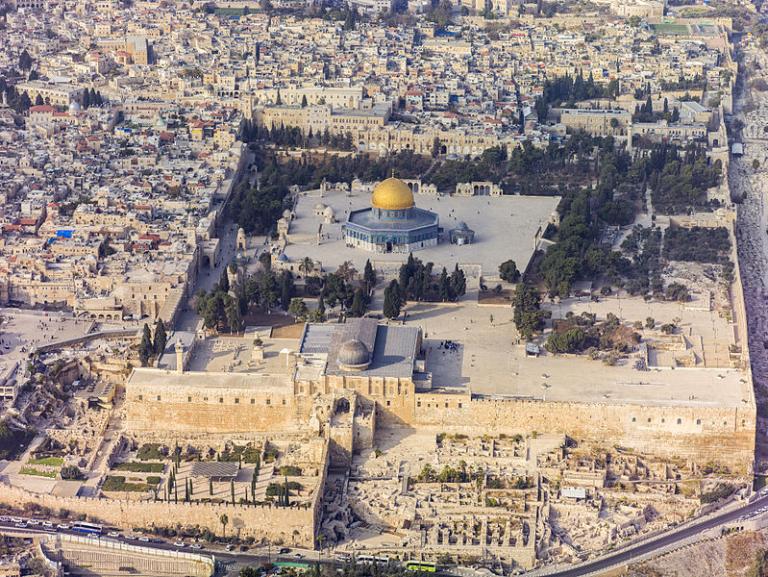

The siege lasted from April to September of 70 A.D. Titus had 60,000 men under his command, highly disciplined and well trained in the use of the latest and most modern siege equipment. The Jewish defenders of the city, by contrast, were only about 25,000 in number and were divided bitterly among themselves. The outcome was never really in doubt, although it was hard work for the Romans at every step. By the end of the siege, the temple had been burned to the ground and those of the Jews who had not been killed outright had either been sent off as slaves or to die in the gladiatorial arenas of Caesarea, Antioch, or Rome itself. Titus’s triumphal arch still stands in Rome where it was erected to commemorate his victory, and on it, carved in stone and still clearly visible, is the great menorah, the lampstand of the temple that he captured and carried off.

[1] John 19:15. In so saying, in proclaiming their sole loyalty to an earthly monarch, the chief priests rejected their heavenly king—in more ways than one. Contrast 1 Samuel 8:6-7; Judges 8:22-23.