(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Poetry was the sole medium of literary expression in pre-Islamic Arabia. In a real sense, it was the only form of art. This is related at least partially to the high Semitic reverence for the word that we’ve already mentioned. It’s also undoubtedly related to the fact that nomads, constantly on the brink of starvation and always on the move, are hardly likely to produce great architecture or monumental sculpture. They need to be able to carry their art, such as it is, with them. So women’s dresses and camel bags come in for some attention. But the lightest-weight form of art anywhere is the memorized word.

The oldest Arabic poems and proverbs that we still possess date back only to about a century before the rise of Islam–that is, to about 500 AD. However, the Arabs were known even in biblical times for their poetry and for what the scholars sometimes call “gnomic wisdom.”[1] In 1 Kings 44:30, Solomon’s wisdom is said to have been so great that it surpassed that of “all the children of the east country” (i.e., the Arabs). And Job’s wise friends, it’s clear, come from north Arabian groups.[2] (Indeed, the book of Job as a whole has been argued by some commentators to have an Arabian origin.)

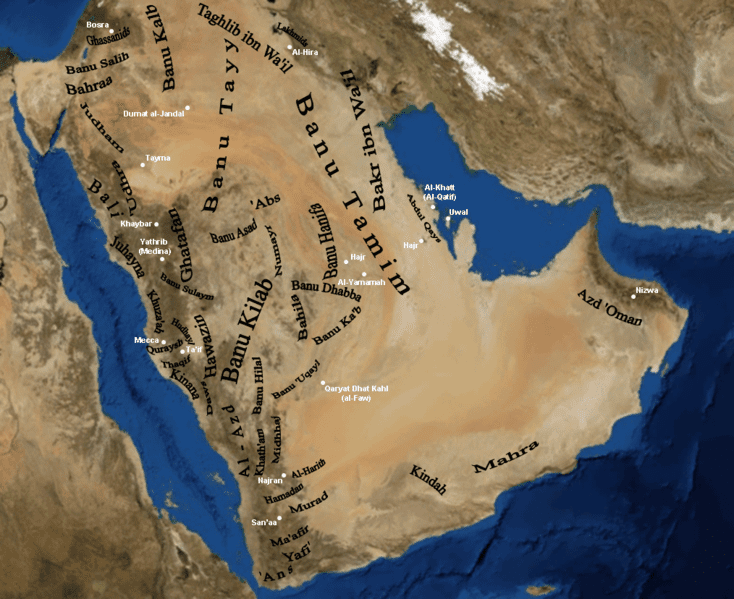

It’s perhaps hard for us in the English-speaking world to picture a society in which poetry wasn’t just for the cultured élite, but for everyone. Nevertheless, this is the picture we get of early Arabia. Poetry was a matter of passionate interest, in much the way, perhaps, that sports captures the attention of many modern men. It was one of the few things that unified the Arabs. Throughout the peninsula, the same Arabic dialect was used for poetry, and the same rules of composition were followed. This made poetry a powerful public relations tool. (We’ve seen to what lengths Hatim of Tayyi was willing to go in order to get three famous poets to praise his family) In fact, the poet’s usual job was to praise his tribe and to vilify the tribes of others. If he was good at his job, if he composed memorable lines, his praise (or his satire) could stick for years and even for generations. As one ancient Arab writer put it, already looking back on the pre-Islamic period,

When there appeared a poet in a family of the Arabs, the other tribes round about would gather together to that family and wish them joy of their good luck. Feasts would be got ready, the women of the tribe would join together in bands, playing upon lutes, as they were wont to do at bridals, and the men and boys would congratulate one another; for a poet was a defence to the honour of them all, a weapon to ward off insult from their good name, and a means of perpetuating their glorious deeds and of establishing their fame for ever. And they used not to wish one another joy but for three things—the birth of a boy, the coming to light of a poet, and the foaling of a noble mare.[3]

[1] From the Greek word gnosis, or “knowledge,” from which we also get the terms gnosticism and gnostic—to say nothing of the common word agnostic for someone who does not know.

[2] A. Jeffery. “Arabians.” In George Arthur Buttrick, et al. eds. The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible. 1:184.

[3] Ibn Rashiq, cited in the translation of Sir Charles Lyall, by Nicholson, 71.

Posted from Breckenridge, Colorado