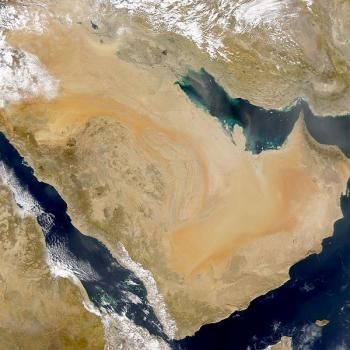

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

From the earliest times, the people of Arabia, though dominantly nomadic, have also included semi-nomadic and even fully settled groups. Sedentary life was overwhelmingly concentrated in the south, with the inhabitants of north and central Arabia being largely nomadic. The two classes of Arabs seldom got along with one another. Arabic literature is full of references to the contempt felt by nomads for settled folk and to the scorn of the people of the settlements for the nomads of the desert.[1] Such desert nomads, or bedouins, roam the Arabian wastelands in units known as tribes. These tribes are really just large extended families, although they also function rather like a government, in that they preserve order, take care of the poor and the orphans and widows, and even occasionally negotiate with one another in much the same way as modern nation-states. Each group possesses, for instance, a recognized pastureland in which to wander. (They don’t just wander anywhere.) But, especially in premodern times, the boundary lines were fluid and were changed constantly by intertribal conflict. Each tribe was sovereign—again, in much the same way that a nation is sovereign—and was led by a chief, or shaykh, who was chosen partly on the basis of descent and partly on the basis of proven valor and wisdom.[2] In theory, at least, tribes were made up of blood relatives and were named after a common ancestor—either real or fictional. Thus, the tribe known as the Banu Hawazin — the “sons” or “children of Hawazin” — would believe themselves to be descended from a progenitor called Hawazin.

The nomads’ seasonal migrations are dictated by the necessities of water and pasturage. They’re obliged to go where the water and the grass are. In this harsh land, the camel is far and away the most important animal, and the Bible often connects it with the Arabs.[3] The head of David’s camel keepers, for instance, was an Ishmaelite.[4] Indeed, even in modern times the camel continues to be the main beast of burden and the principal means of transport for these nomadic tribes. But sheep and goats were also important to ancient Arabs.[5] And the horse, which isn’t nearly so well suited to life in the desert as the camel, was a highly-esteemed luxury.[6] The most common nomadic dwelling—useful because it’s mobile—was and is a tent. (When Nephi, in the shortest verse in the Book of Mormon, records that his father “dwelt in a tent,” he tells us volumes, I think, about the lifestyle that he and his family had adopted while in the desert en route to the land of promise.[7] Tents are a prominent part of the first chapters of 1 Nephi.) Pictorial representations of these tents on ancient Assyrian monuments show them to have been much the same in ancient times as they are today. Modern bedouin women, like their ancient counterparts, do the domestic work around the tent, of which half is considered “women’s quarters.” They tend to the small animals, prepare food, and weave. The males, on the other hand, take care of the camels and the horses, hunt, and, of course, raid. Judges 8:21-26 mentions a style of ornamentation of men and camels that remains common today. And the nose ring and bracelets given to Rebekah are still the ornaments given to a bedouin girl.[8]

The “sons of Heth” from whom Abraham bought a burial ground for his family in Hebron, and among whom Esau found wives, seem to have been Arabs.[9] And, intriguingly, the “ravens” who fed Elijah “by the brook Cherith” in the wilderness may well have been the bedouin Arabs of the region. According to this view, which remains rather speculative, 1 Kings 17:4 should read “I have commanded the Arabs to feed thee there.” (The Hebrew equivalents for English raven and Arab are quite similar and could easily have been confused with one another over the many centuries of the transmission of the biblical text.)[10] If such an interpretation is true, we see an early instance of Arabians as agents of God, receiving revelation or inspiration from him.

The Midianites are an Arabian group of bedouins who play an important role in the scriptures. They were Ishmaelite traders who took caravans to Egypt, as mentioned in the story of Joseph.[11] The prophet Isaiah speaks of their “multitude of dromedaries [camels]” and of their great wealth in gold and incense, brought up from Sheba in South Arabia.[12] In the story of Gideon, “the Midianites came up, and the Amalekites, and the children of the east . . . with their cattle and their tents, and they came as grasshoppers for multitude; for both they and their camels were without number” (Judges 6:3, 5).

Some Midianites, at least, seem to have been a pastoral people, a people of shepherds. It was among them that Moses found his wife after he had fled from before the pharaoh, and it was to them that he led the children of Israel after their exodus from Egypt.[13] In at least one case, a Midianite appears to have served as an authorized agent of the Lord: According to Doctrine and Covenants 84:6-7, Jethro, the Midianite chief, held the priesthood and conferred it upon Moses. This goes considerably beyond what the Bible says about him. But it may receive some support from Arabic tradition, which seems to know Jethro under the name of Shu’ayb, whom it views as a great prophet and preacher who spoke with authority from God.[14]

[1] This is not altogether unlike the relationship between Nephites and Lamanites in much of the Book of Mormon. Some writers on the claims of the Restoration have argued that, in the friction depicted between urban Nephites and wandering Lamanites, the Book of Mormon reflects early American feeling for the “yeoman farmer.” But, in arguing this, these writers only reveal their lack of acquaintance with ancient history and the Near East. The dispute between “ranchers” and “farmers” is not merely American. It goes back to Cain and Abel.

[2] The work shaykh—sometimes spelled sheik and sheikh, and often mispronounced as if it were the French word chic—means “elder.” Someday, when Latter-day Saint missionaries take the gospel to the Arabs, we may have missionary shaykhs. Shaykh is also often used by Arab newspapers to translate the title senator, since that English word too was originally connected with the idea of age. (Think of senile!)

[3] As in Genesis 37:25; Judges 6:5; 7:12; 8:26; 1 Samuel 15:3; 30:17; 1 Kings 10:2; 1 Chronicles 5:21; 27:30; 2 Chronicles 9:1; Jeremiah 49:29, 32.

[4] 1 Chronicles 27:30.

[5] Ezekiel 27:21.

[6] See the admiring words of Job 39:19-25. A. J. Arberry, Aspects of Islamic Civilization (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967), 19-31, furnishes specimens of pre- Islamic Arabic poetry in excellent translation. Several passages are in praise of the nomads’ horses and camels.

[7] 1 Nephi 2:15. The tents of the ancient Arabs, sometimes associated with camels, are mentioned in the Bible at places like Judges 8:11; Psalms 83:6; 120:5; Jeremiah 49:29, 31 32; Ezekiel 38:11.

[8] Genesis 24:22, 47.

[9] Genesis 26:34; 27:46; 36:2. They were almost certainly not the same people as the more famous “Hittites” of Anatolia, whose Indo-European language, like modern Persian, is (very) distantly related to English.

[10] 1 Kings 17:4, 6. See A. Jeffery, “Arabians,” in Buttrick, et al., eds., The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, 1:182; John Gray, I and II Kings: A Commentary (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1963), 338-39.

[11] Genesis 37:24-36. Judges 8:22-27 also links the Midianites with Ishmael (and with camels).

[12] Isaiah 60:6.

[13] Exodus 2-3, 17.

[14] See, in the Qur’an, 7:85-93.

Posted from Estes Park, Colorado