Humans always want to know “why.” Especially children. It seems that it’s an inherent part of the human mind.

At very young ages, kids ask why something is the way it is. But when an adult answers the question with “because x,” the child will ask “But why x?” And if that adult says “x because y,” the child will ask “But how come y?” And when the adult explains that “y because z,” the child will ask “But why z?”

Science answers why questions. Some of them, anyway. It explains why hydrogen, conjoined with oxygen in a certain way, becomes water. Other why questions, though, it leaves untouched. Is there a purpose to the cosmos? Why does it exist? Science has no answer for that question if purpose or intent is what is being sought.

Really, in a way, science’s questions are mostly if not entirely how questions. How is water made from hydrogen and oxygen? How did stars come to be? How was the Grand Canyon formed? How did Darwin’s finches diverge the way they have?

But any answer that emerges out of science will invariably suggest another question, and another, and another. Why do the planets move as they do? Because they follow Newton’s law of universal gravitation. What is the gravitational constant in that formula? About 6.67408 × 10-11 m3 kg-1 s-2. But why is that the gravitational constant? Why not some other figure?

One very simple (simplistic) view of this matter holds that, when a person gets to the point that she doesn’t know the answer to such a question, she has just two options: She can either say, “I don’t know” (this is the admirable, open answer) or she can say, “because God” (which is plainly the stupid, inquiry-ending, curiosity-killing theistic answer). All lines of questions, according to this very simple view, need to end in one of those two places.

For many, God is the ultimate answer to all why questions—the first cause of anything. Others contend that to invoke God, ever, isn’t really to answer the question at all. Rather, it’s to give up on scientific investigation.

Some are suggesting that the great astronomer Allan Sandage, whom I cited in a previous post, did precisely that — gave up on science and, even, on reason itself — when, awed by the sheer scope and magnitude and order of the cosmos, he became a committed Christian theist (while, it must be said, continuing to work under the guise of a highly respected astronomer).

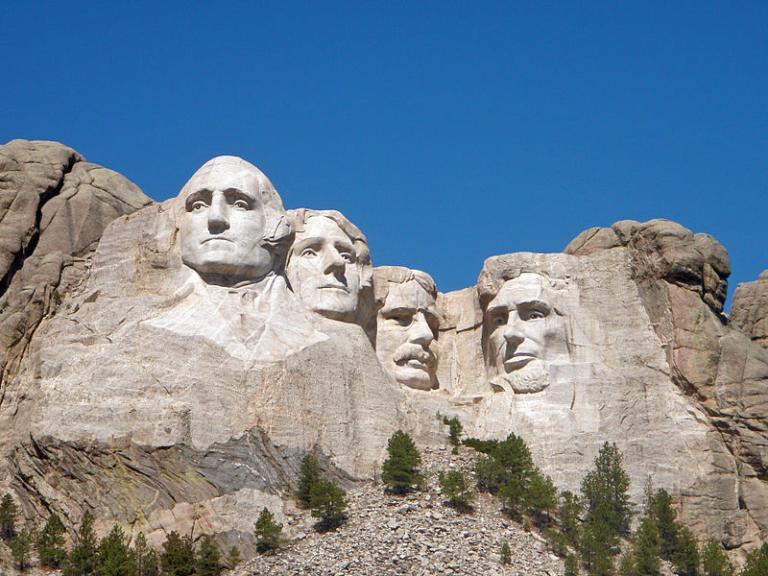

I would like to call attention to another case in which people commonly surrender their reason and their commitment to science: Mount Rushmore.

Shallow thinkers often imagine that they have “explained” Mount Rushmore by invoking the effects of a carbon-based biochemical system labeled Gutzon Borglum. Plainly, though, to invoke some sort of intelligent agency here isn’t really to answer the question of Mount Rushmore at all. Rather, it’s to give up on scientific investigation. Gutzon Borglum needs to be explained on the basis of neural networks and electrochemical processes and, indeed, on the basis of a chain of physical events leading back to the primordial singularity of the Big Bang.

If, that is, “Borglum” even existed. After all, historiography isn’t a science. History is imprecise. Eyewitnesses are often mistaken. Many of them lie. And photographs can easily be falsified. (Plenty of money has been made from selling tickets and trinkets to gullible tourists at Mount Rushmore. It’s obvious where self-interest lies in this case.) I strongly suspect that, when all is said and done, the four “portraits” on Mount Rushmore will be seen to be the product of undirected erosion by wind and water. Do they look like the defunct carbon units called Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt? Well, yes. They seem to. But in an infinite multiverse such as ours, it was and is literally inevitable that a world would exist, somewhere, in which seeming likenesses of four carbon units (out of many billions!) would be randomly created by natural processes.

It’s flatly unscientific to imagine otherwise.