(Wikimedia Commons public domain image by “Sailko”)

Arabic influence is clearly visible in the arts and crafts of the West. Many materials associated with Western clothing were originally of Arab design. Thus, damask, a silk or linen with a design visible from either side, is named after the great Syrian city of Damascus. Muslin, a thin cotton cloth, comes to us from Mosul, an important town in Iraq. Sicilian silk weaving, for which that island is famous, is modeled on the Arab silk industry and in fact dates from the days when the Arabs ruled Sicily. Mohair and cotton and kaftan are all originally Arabic terms. Satin comes to us from the Arabic name for the great medieval Chinese seaport of Tzu-t’ing, where the fabric was first manufactured; it is eloquent evidence of the vast extent of Arab merchant trading. The term fustian, which today (for some odd reason) generally means “pompous language,” or “bombast,” originally identified a thick, twilled cotton cloth with a short nap that was usually dyed dark and dull. The word seems to come from Fustat, the name of the Arab military encampment founded in Egypt right after the conquest of that cotton-producing country. Another odd transformation was undergone by the word baldachin. It originally referred to a rich embroidered cloth of silk and gold, a brocade. Then it came to refer to a canopy, originally to one made of that particular cloth or brocade. Eventually, though, it seems to have come to refer to canopies in general. It is for this reason that we now have Bernini’s early seventeenth-century baldacchino, the centerpiece of the most important church in Catholic Christendom, St. Peter’s Basilica at Rome. This huge baroque canopy, standing under the main dome and covering the high altar of the Pope’s own church, was intended to mark the tomb of St. Peter. Nearly a hundred feet high, it is made not of brocade, but of bronze. But whatever transformations in meaning the word may have undergone, it is clear that it derives from Baldac, a medieval corruption of Baghdad.

Other Western crafts have received important contributions from the Arabs. Dutch blue china or delftware, for instance, seems to have been invented by the Arabs rather than by the Dutch, who merely borrowed the technique. And Damascus and Toledo blades, carryovers from the old weapons manufacturers of Muslim Spain, tell their own story of Arab influence, as does Moroccan leather.

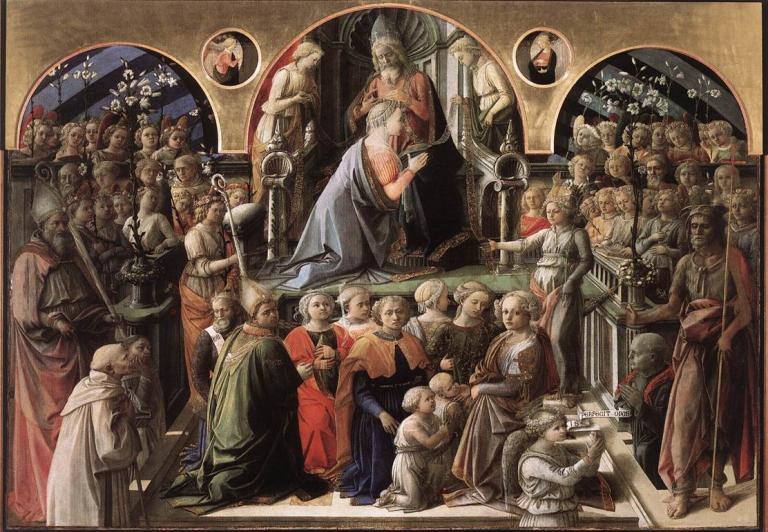

But the fine arts also receive their share of Arab influence. Sometimes this is very striking, as in Fra Lippo Lippi’s Italian Renaissance painting of “The Coronation of the Virgin,” in which the angels surrounding the Madonna hold transparent ribbons inscribed with Arab words in praise of Allah. This is not so surprising because, ironically, many of the church vestments used in the Roman Catholic liturgy during the period were of Arab manufacture. This is apparent in certain paintings of Giotto and Fra Angelico.

The word arabesque tells us all we need to know about its inspiration or origin. The Italian campanile, the bell tower that is so characteristic of Italian churches, seems to have been inspired by the Islamic minaret, or prayer tower. And it is only a short jump from the marvelous campanile at the Piazza di San Marco, in Venice, to the look-alike Sather Tower on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. And from there, it is no great distance to other bell towers on university campuses across the United States, including the carillon tower at Brigham Young University. Arab influence on certain buildings is undeniable. For example, the medallions of the Christian saints in the Norman Palatine Chapel in Palermo, Sicily, bear inscriptions in Kufic Arabic script.