Are you aware that you can watch Witnesses and Undaunted, right now, at no charge? Do you realize that you could do that tonight? In fact, tonight would be a really good night to watch one or both of them. Maybe an especially good night, if your team loses the Super Bowl. Or, alternatively, if your team wins the Super Bowl. After all, you’ve already got the chips and dips and salsa and root beer.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

At one point, in an exhibit on pharaonic Egypt that my wife and I visited a year or two ago in Sydney, Australia, the exhibit signage spoke about the ancient Egyptian belief that the “skin” of the gods was gold, because of its brilliance and because it doesn’t tarnish. At another point, referring to Pharaoh Sheshonq II or Shoshenq II, the signage described the gold toe and finger coverings and other gold items with which he was buried.

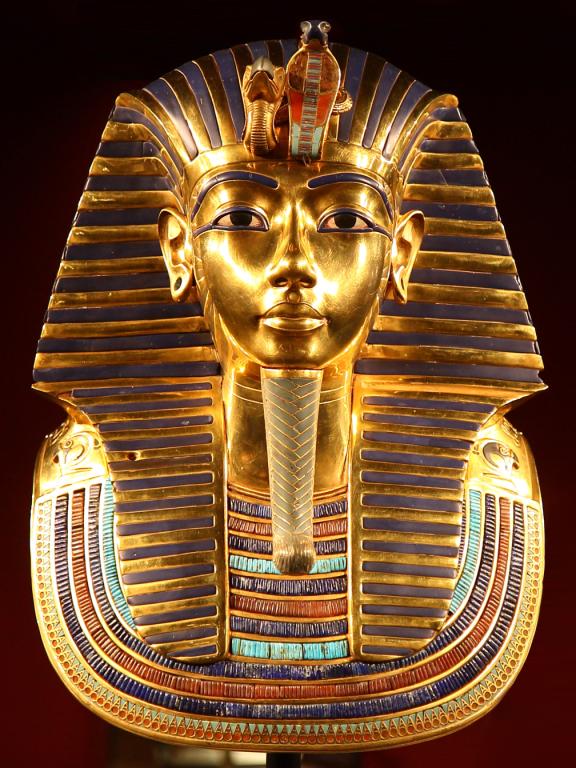

With that in mind, I found myself wondering about all the gold associated with pharaonic burials. I was specifically thinking of the gold face masks of the royal mummies. These are most famously but not solely illustrated by Tutankhamen’s famous mask, which was still housed in the Egyptian Museum on Tahrir Square in Cairo when we were last there in January 2023 but which may possibly have been transferred to the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza since then. Sheshonq II himself had such a funerary mask. (See the image above.)

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

Were the ancient Egyptian artists trying to represent the radiance that they thought characterized immortal divine beings such as the gods (and the deified pharaohs who were now numbered among the gods)? And where would they have gotten this idea of divine radiance?

Those who have encountered such divine beings often refer to the light that accompanied them. One of the children who saw seemingly angelic figures during the famous 1986 “Cokeville Miracle” in western Wyoming described them as having “light bulbs inside them.” (Analogous comments are not uncommon in accounts of near-death experiences.) Moses, who lacked any experience with electric lighting, met the Lord at Mt. Sinai amid what he understood as flame:

And the angel of the LORD appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush: and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed. (Exodus 3:2)

The Book of Mormon records the prophetic call of Lehi in part as follows:

And it came to pass as he prayed unto the Lord, there came a pillar of fire and dwelt upon a rock before him; and he saw and heard much; and because of the things which he saw and heard he did quake and tremble exceedingly. (1 Nephi 1:6)

In one of Joseph Smith’s accounts of his 1820 First Vision, he indicates that when he saw the column of light descending in which, shortly, he would see the Father and the Son, he was momentarily afraid that, when it touched the trees, they would burst into flame. (He, too, lived in “a world lit only by fire.”). Consider, too, this passage from the canonical account of that vision:

I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head, above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me.

It no sooner appeared than I found myself delivered from the enemy which held me bound. When the light rested upon me I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. (Joseph Smith – History 1:16c-17a)

And this passage, recounting the first visit to Joseph Smith of the Angel Moroni:

I discovered a light appearing in my room, which continued to increase until the room was lighter than at noonday, when immediately a personage appeared at my bedside, standing in the air, for his feet did not touch the floor.

He had on a loose robe of most exquisite whiteness. It was a whiteness beyond anything earthly I had ever seen; nor do I believe that any earthly thing could be made to appear so exceedingly white and brilliant. . . .

Not only was his robe exceedingly white, but his whole person was glorious beyond description, and his countenance truly like lightning. The room was exceedingly light, but not so very bright as immediately around his person. When I first looked upon him, I was afraid; but the fear soon left me. (Joseph Smith – History 1:30-32)

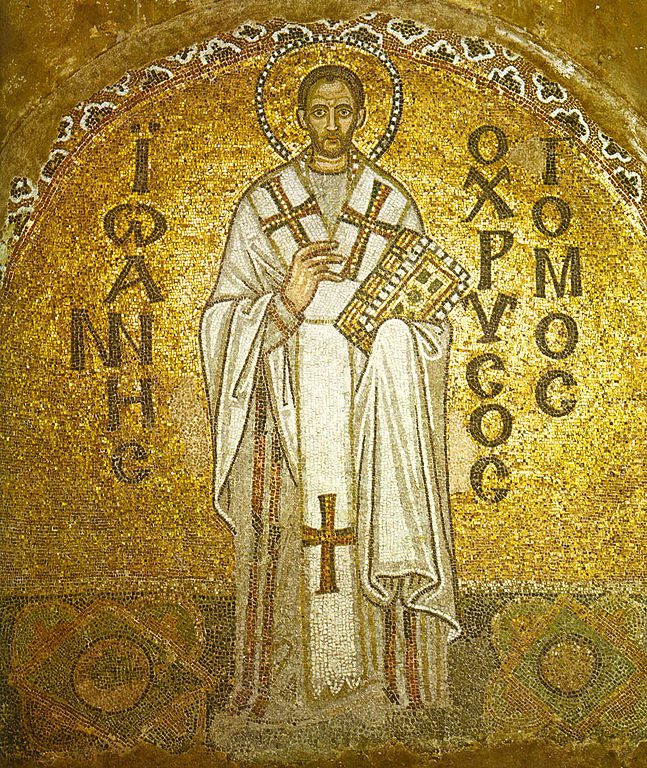

Were the ancient Egyptians, perhaps guided by accounts of actual visitations and/or memories of near-death experiences, attempting with their gold to capture something of the radiant glory of celestial beings? (The much later Byzantines seem, to me anyway, to have been trying something along the same lines with their golden mosaics.)

I have been very impressed by my recent reading of Brant Pitre, Jesus and Divine Christology (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2024). Here’s a passage from one of Dr. Pitre’s subordinate arguments that reminded me of my reflections on Egyptian and Byzantine gold art and, more broadly, on the divine light, above:

[A]fter reaching the top of the mountain [of Transfiguration], Peter, James, and John experience a kind of heavenly vision in which the appearance of Jesus is altered so that his clothing becomes luminously “white” (Matt 17:2; Mark 9:3; Luke 9:3). The luminosity of Jesus’s garments is extremely significant: in both Jewish Scripture and early Jewish apocalypses, luminously white garments are often worn by heavenly beings.

For example, in the book of Psalms, “the Lord” is described as being “wrapped in light as with a garment” (Ps 104:2) — something that is “part of the imagery of appearances of ancient Near East divinities.” Even more striking, both the book of Daniel and the early Jewish apocalypse of Enoch describe God in heaven as wearing dazzlingly white garments:

As I [Daniel] watched,

thrones were set in place,

and an Ancient of Days took his throne;

his clothing was white as snow

and the hair of his head like pure wool;

his throne was fiery flames,

and its wheels were burning fire. (Daniel 7:9, slightly modified)And I [Enoch] was looking,

And I saw a lofty throne . . .

And the Great Glory sat upon it;

his raiment was like the appearance of the sun

and whiter than much snow,

And no angel could enter into this house and behold his face

because of the splendor and glory;

and no flesh could behold him. (1 Enoch 14:18, 20-21, trans. George W. E. Nickelsburg)In both passages, Daniel and Enoch are described as seeing the luminous garments of God in the context of an apocalyptic theophany in which they (somehow) “see” God (cf. Dan 7:1-18; 1 Enoch 14:1-17). This strongly suggests that Peter, James, and John’s vision of the transfiguration of Jesus’s clothing is likewise both apocalyptic and theophanic. Just as Daniel and Enoch experience an apocalyptic vision in which the God of Israel appears in heaven dressed in supernaturally white clothing, so now Peter, James, and John have an apocalyptic vision in which Jesus appears on the mountaintop dressed in luminously white garments.

If this assessment is correct, then the Synoptic accounts of the transfiguration suggest that Jesus is not merely a human being; he is also a heavenly being — one who temporarily lifts the visible appearance of his humanity to give his disciples a glimpse of his invisible heavenly glory. In this regard, it is significant that other human figures in early Jewish literature only become luminous after death, once they have been raised from the dead (Dan 12:6-7) or are exalted into heaven (Testament of Abraham 11:4-9). By contrast, Jesus appears dressed in luminous garments during his earthly life. In other words, Jesus is being depicted as a human who is already a heavenly being, but whose heavenly identity is currently hidden under his ordinary human appearance. (90-91, italics in the original)

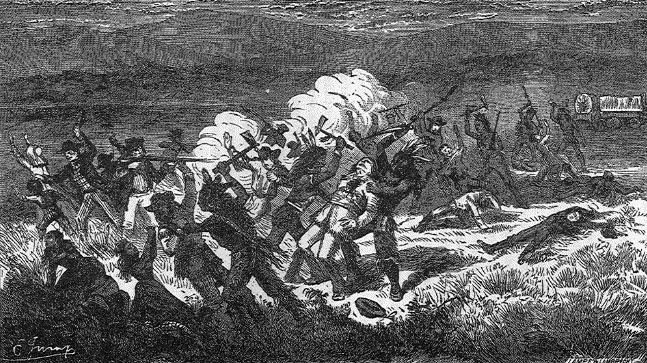

On a dramatically different note: Here’s a short but helpful article on the OUPblog that is maintained by Oxford University Press It’s by Barbara Jones Brown, who, with Richard E. Turley Jr., recently published Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath through, well, Oxford University Press: The article is entitled “Fact and fiction behind American Primeval.“

And here’s another critical piece about American Primeval: “The Harm of Egregiously Misleading Historical Fiction”

Good news, though: You can find out here where the Interpreter Foundation’s Six Days in August is streaming. Only, though, if you want a rather different cinematic take on Brigham Young than that advanced by Netflix in its American Primeval miniseries.