(Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons)

Over the course of many years, students of the traditions about Muhammad and his companions worked out a complex and sophisticated system for testing and classifying hadith. Some hadith reports were ranked as sahih, or “sound,” which is to say that all of the links in their isnads, their chains of transmission, were good ones going back directly to the purported source of the tradition, who was usually the Prophet himself.[1] A slightly less reliable group of traditions were determined to be hasan, “good.” These “good” traditions had a weak link in their chain of transmission—someone whose integrity was questionable or whose contact with another transmitter was subject to doubt—but they were nevertheless acceptable if they were really needed because there was some outside corroboration that led scholars to think they were most likely true. Finally, and acceptable for very little, were those hadith reports that were judged to be da’if, or “weak.”[2] They would be used only when a judge or a theologian was desperate, and they would not be convincing to many.

A mastery of the thousands of hadith circulating in the Islamic world was what constituted ‘ilm, or “knowledge,” and those who had such knowledge were the “knowers” (‘ulama’) par excellence.[3] Eventually, the ‘ulama’ came to be a kind of rabbi class, the nearest thing that Islam has to a clergy. Authority did not proceed from ordination or priesthood, but from knowledge of the law.

Finally, after the process of seeking out and sifting hadith reports for many decades, the time came for gathering the ones that had been adjudged to be reliable into accessible works of reference. The need was especially pressing in the law courts of the empire. It is to this that we owe the great collections of “sound” hadith that have taken on almost scriptural status in Sunni Islam. Foremost among these are two multivolume works, each entitled al-Sahih, compiled by al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Muslim (d. 875). As these and other manuals of hadith won acceptance, it was a knowledge of them—extending to memorization—that came to constitute real ‘ilm and would win an aspiring young scholar a place among the ‘ulama’.

Al-Bukhari’s Sahih, which holds undisputed pride of place among Sunnis, is worth describing here in a bit of detail. It is composed of ninety-seven books divided into a total of 3,450 chapters. Each book is devoted to a general subject, such as prayer, fasting, alms, testimony, buying and selling, marriage, and the like. About 2,762 separate hadith reports occur in Bukhari’s volumes, but they are often repeated under different headings, for a total of approximately 7,300. As the name of his vast work indicates, it is composed only of hadith reports that were judged by Bukhari and his associates to be sahih, or “sound.” These were the best he could find. Muslim tradition says that these “sound” reports were culled from the best 200,000 hadith Bukhari had encountered in the course of a lifetime spent crisscrossing the Arab empire in quest of anecdotal material about the Prophet and his companions. The obviously spurious or biased reports he had not even taken into account. These facts give some idea of the magnitude of the problem of forgery faced by Muslim scholars and jurists in those early centuries.

Western scholars, in their turn, have been quick to criticize the classical Islamic method of testing hadith by their chains of transmitters, or isnads. They have pointed out, no doubt correctly, that anybody clever enough to forge the substance of a plausible hadith report could also, if he knew it would come under scrutiny, forge a perfectly plausible chain of transmitters for his report. In fact, as biographical dictionaries began to appear, he would have at his disposal a highly useful set of reference works to help him do precisely that. Such criticism is well aimed, it seems, but there can be little doubt that Muslim isnad-criticism did manage to exclude the most blatantly propagandistic forgeries of the first and second centuries after the Prophet. And we must also be grateful for the impetus given by these investigations of hadith and hadith-transmitters to the study of history, which grew up as a side—or sub—discipline to them.

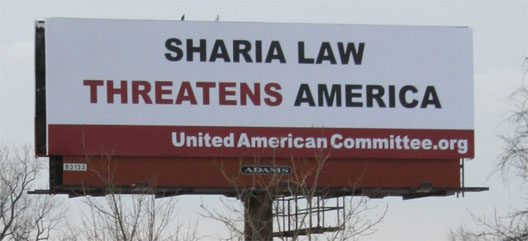

The greatest contribution to the study of hadith, however, was the creation of the vast, complex, and sophisticated body of Islamic law known as the shariah.[4] Early on, the ‘ulama’ began an attempt to codify Islamic law, to systematize it on the basis of the Qur’an and the sunna. Several basic principles governed their work. The first and perhaps most important was that, if clear commands existed in the Qur’an or in authenticated hadith, those were to be accepted without human speculation or modification. (This is actually less rigid than it sounds, though, since the human mind had to determine how widely a given rule applies and precisely what it means. This called for the minute study of Arabic grammar and of the meanings of words, including metaphors, and allowed for some differences of opinion and emphasis.) If, on the other hand, a situation was not covered in either the Qur’an or the hadith, most jurists would permit the use of “analogy” (qiyas), by which an old principle could be applied to a new situation.[5] For instance, if the Prophet had forbidden the marriage of a Muslim girl to a pagan Arab on the grounds that he worshiped many gods, a later Muslim judge might rule against the marriage of a Muslim girl to a Hindu, reasoning by analogy from the first case.

[1] The Arabic word sahih is pronounced “sa-HEEH”—with the final “h” being sounded as if it began a syllable.

[2] Da’if is pronounced “da-EEF.”

[3] This word, which is spelled in a wide variety of ways by Western scholars, is pronounced roughly “oo-la-MAA.”

[4] Pronounced (roughly) “sha-REE-ah.”

[5] Pronounced (approximately) “kee-YAASS.”