(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Changing gears, it is worth noting that many terms connected with warfare have entered our Western languages from the Arabs. (Perhaps this says something of the state of war that has existed between Christendom and the world of Islam through much of their shared history.) Some of these words have amusing histories in themselves. Our navy rank of “admiral,” for instance, seems to have arisen out of a misunderstanding of the original Arabic word. The most likely explanation is that admiral derives from the Arabic title amir al-bahr, “commander of the sea.” Westerners, so the theory goes, heard this as amiral bahr, or, as they interpreted it, “Admiral Bahr.” Actually, of course, bahr is not somebody’s name, but merely means “sea,” and amir al- means “commander [of] the.”

Other borrowings were more straightforward. The Arabic ghazw (“raid”) entered English via Italian as razzia. Our word magazine, which first meant “warehouse” or “storehouse” (of weapons or cartridges, as in a powder magazine or the magazine of a gun), only began to mean a “storehouse” of information or of entertainment—that is, a periodical publication—in the 1700s. It comes from the Arabic word makhzan (“storehouse”). Another word for much the same thing, arsenal, meaning a place where weapons and ammunition are either manufactured or stored, is a corruption of the Arabic dar al-sina‘ or dar as-sina‘ (“house of manufacturing”). The weapons in such a place are likely to be of different “calibers.” This word, like its relatives caliper, calibrate, and calibration, comes to us from the Arabic qalib, meaning “form,” “mold,” or “model.” Those who enter into an arsenal or a powder magazine do so, incidentally, at their own “risk.” (Arabic rizq signifies the things bestowed upon us by God— usually for our good, but possibly for ill.)

Two other words borrowed from Arabic deserve mention here, perhaps. The first is assassin. Unfortunately, few readers will be surprised to learn that this word comes to the West from Arabic, but the history of the term is interesting nonetheless. The original “Assassins” were an order of religious revolutionaries, a sect of Shiite Muslims, who were founded toward the end of the eleventh century and who made a great impression on the minds (and sometimes the bodies) of the Crusaders. The legend of the Assassins claims, almost certainly without basis in fact, that they would work themselves up to perform terrible deeds of political murder by using what we today know as marijuana or hashish (as the Arabic term itself has entered the English language). That is supposedly why they came to be called the hashishin.[1] When the Crusaders returned to Europe, they brought with them horrifying tales of these fearsome political “assassins,” and the word has remained sadly useful in our vocabulary ever since.

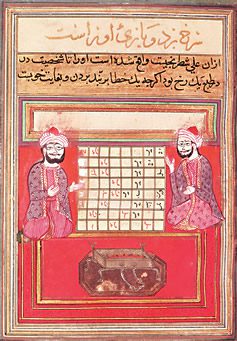

The second word has to do with a more cheerful subject (except for those of us who are routinely humiliated at the game)— namely, chess. Chess is a very old form of entertainment, with roots deep in the military tactics of the Near East. (It is nothing more than a war game, which is obvious when you think about it.) Since it was royalty who were most concerned with matters of war in ancient times, we are not surprised to learn that the very word chess comes from the Persian term shah, or “king.” (You’ll have to trust me on this one; the process by which shah became chess is too long and too complex to detail here.) The relationship is less heavily disguised in the related English word checkers, which is also related—isn’t this fun?—to the British Exchequer, or royal treasury. And the German name for chess, Schach, makes the connection absolutely clear. Finally, once we have this royal connection in mind, it is no longer difficult to understand the chess term checkmate, which otherwise makes no sense at all in English. It is nothing other than the Persian-Arabic phrase shah mat (“the king is dead”), which also shows up in the Russian name for chess, shakhmaty.

The idea behind the notion of “checkmate” is worth pursuing. Players of chess will remember that nothing else really matters in the game except neutralizing your opponent’s king. Even if the other player still has his queen and all his other pieces, he loses the game if his king is taken out. This was a very common idea in antiquity; chess merely reflects premodern military thinking. A clear historical illustration can be found in a book called the Anabasis, a classic piece of autobiography written by the ancient Greek writer Xenophon. Xenophon was part of a force of Greek mercenary soldiers who set out for Persia to help put a particular member of that nation’s royal family on the throne in place of his brother. When the battle began, things were going well until their leader, inflamed by the victory that was soon to be his, went too far ahead of his bodyguards and was killed. Immediately, although poised on the brink of triumph, his armies melted away and fled. The war was over. The “king” was dead. Checkmate.

Why do I find this of particular interest? Because a similar idea seems to occur in the Book of Mormon. When Teancum managed, at great personal risk, to sneak into the tent of Amalickiah on New Year’s Eve and drive a javelin through that evil man’s heart, “the Lamanites… were affrighted; and they abandoned their design in marching into the land northward, and retreated with all their army into the city of Mulek, and sought protection in their fortifications.”[2] Later, Teancum died in a successful attempt to do the same thing to Ammoron, Amalickiah’s equally wicked brother and successor.[3] Why would Teancum be willing to undergo so great a risk merely to get the king? Because when the king is dead, the game is effectively over. That this authentically ancient idea pervades the Book of Mormon is shown by the way the book uses the term destroy. The Jaredites were utterly “destroyed,” and yet it is clear that many survived. What is actually meant is that their leadership was eliminated, not necessarily that every last man, woman, and child of them was killed.[4] Thus, as in so many ways, the Book of Mormon seems to reveal its connections with the Near East. (Chess as evidence of the gospel!)

[1] The pronunciation for these two words is “ha-SHEESH” and “ha-sheesh-EEN.”

[2] See Alma 51:33-52:2.

[3] Alma 62:35-39.

[4] For good discussions of this matter as it relates to the Book of Mormon, see Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, Volume 5 in the Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, edited by John W. Welch, et al. (Salt Lake City and Provo: Deseret Book and the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1988), 237-54; John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo: Deseret Book and the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1985), 119-20.