On this 2020 American Thanksgiving Day, I’m acutely aware of my inability to gather safely with members of my extended family. Some are across the country. Some are altogether out of the country. Some are close but are vulnerable to the coronavirus pandemic. One of our grandchildren is now more than a year old, yet we still haven’t actually met her. (We plan at least three Zoom gatherings for later today.) Many are simply, sadly, gone. At all times, though, I’m grateful for my family, and for the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ and the ordinances of the temple, which assure me that I will see the departed members of my family again, that our connection with the living and the dead is eternal, and that we will still be family in the world to come.

Obviously, naturalistic materialism can make no such promise. But neither can traditional Christianity, although (for at least the past couple of centuries) many Christians have pictured themselves enjoying heaven with parents and children and kin, revealing an instinct or an intuition far sounder than their theologians, who have sometimes denounced their hope for heaven as mere sentimentality if not altogether as false doctrine.

In the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso of Dante’s great early-fourteenth-century Divina Commedia, for instance, postmortem spirits are depicted — with very few exceptions (e.g., the adulterous lovers Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, of Inferno V.73-142, who are linked in the torment of their never-ending damnation) — as separated individuals, as social atoms, not as spouses or members of families.

The oldest standard English-language wedding vows still in mainstream Christian use date back through Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s 1549 Anglican Book of Common Prayer to at least the so-called “Sarum rite” that governed Church rituals in England from the eleventh century to the advent of the Reformation. Strikingly, they pronounce the end of the marital relationship on the very day that they initiate it:

I, _____, take thee, _____, to be my wedded Husband, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love, cherish, and to obey, till death us do part, according to God’s holy ordinance.

The Quakers, dissenting from the Church of England, were once even more explicit on this point. Their earliest standard wedding vows expressly identify God’s hand as inescapably ending human marriage:

Friends, in the fear of the Lord, and before this assembly, I take my friend AB to be my wife, promising, through divine assistance, to be unto her a loving and faithful husband, until it shall please the Lord by death to separate us.

Across the Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, and other Protestant traditions, wedding rites commonly include some variant of a familiar pledge to be faithful to one another “as long as you/we both shall live.” The formal bond between husband and wife and, thus, between parents and children is not envisioned as surviving death.

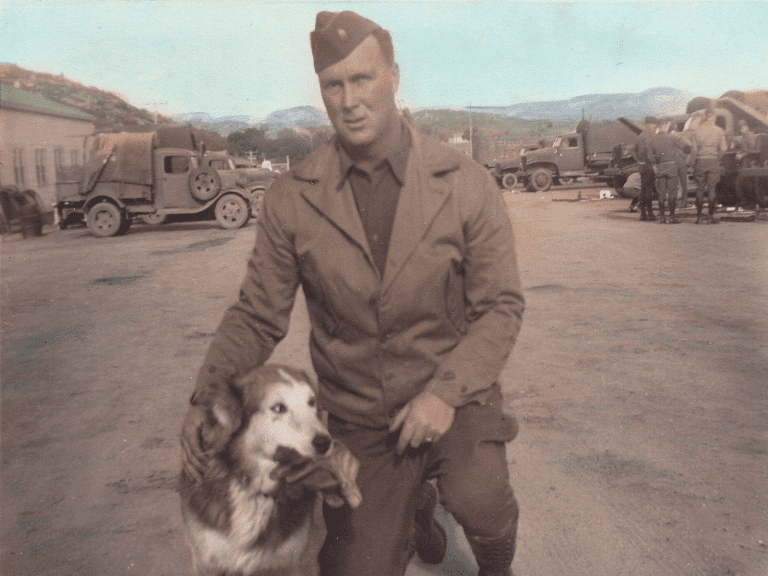

But I want to see my father and my mother again. I make no secret of that. So many things have happened that I would like to tell them about. So many things that would amuse them. In each case, it was time for them to go, but that didn’t ease the pain very much for me. For years, since I lived hundreds of miles away and was often on the road, I spoke to them every night by telephone. And then, suddenly, there was nobody left to call. At their funerals, I predicted that no day would go by without my thinking of them. I wondered afterwards whether, as years and decades passed, that would really prove to be true. But it has. Every day awakens memories. And, for some reason that I can’t begin to explain, looking at the moon and the stars in a clear night sky almost invariably starts me talking to them, silently or even, sometimes, audibly.

I want to see my brother again. The day of his shocking and sudden death in 2012 remains one of the worst of my life. I had so much more that I wanted to do with him. I have so many questions that I wish I could ask him. And, again, there are so many things to discuss. We weren’t done. I wasn’t ready to say goodbye.

I look forward to getting to know my first grandchild, whose brief earthly sojourn in mid-2014 never allowed her even to leave the Florida hospital in which she was born. I want very much to meet her:

My grandmother grew up here, on a farm called Søgnesand that still exists on the water’s edge in the lower lefthand corner of this photograph.

I never knew either of my grandfathers. Both died before I was born. My grandmothers both died when I was five years old. I’m not sure that I remember my maternal grandmother at all; she lived in Utah while I grew up in California, and I may simply be remembering photographs of her (although I have one very clear image in my memory from the day of her funeral in St. George). I think that I recall my paternal grandmother’s whispery but kind older lady’s voice, with her heavy Norwegian accent. (Alone of her family at the time, she came to America in her late teens; she never saw her parents again.). In her last years, she and (for a time) her husband, my grandfather, lived in southern California, where most of her children had settled and where the weather was friendlier to old age than in North Dakota. But maybe I’m remembering her younger sister, Christina, whom I met once and who lived to be either 105 or 106. I always felt slightly deprived because, unlike my friends growing up, I had no living grandparents. I want to get to know them.

I miss my mother-in-law, Ruth Stephens, whom we lost on 6 April 2013 after we had already lost her to a painful battle with dementia that had obscured and then erased her personality, her musical and cultural interests, her zest for learning and for travel — we traveled many times, domestically and internationally, with her and my father-in-law — and her often sparkling wit.

My aunts and uncles are all gone now. And the men who worked for the family construction business in South El Monte — Warren Salmon, Red Faler, the Beltran brothers (Tino and Frank and Hank), Charlie Felix, Joe Esparza, and others, some of whom, before I really understood the meaning of the word, I knew as “uncles” — they’re gone, too. Every one of them. So, too, are all the neighbors that I knew there in San Gabriel, and the others of my parents’ generation — the Smiths, the Funks, the Brintons, the Gilbrides, and more — with whom I grew up camping in the California desert and on California’s beaches, rockhounding, and exploring the “Mother Lode” gold country. Every time we drive past the Afton Canyon exit on I-15, which has happened more and more seldom in recent years, it’s tradition in my family for everyone to put his or her right hand over the heart out of veneration for the site of so many memories. Afton Canyon was a place for riding motorcyles and hunting for geodes and hearing tall tales around the campfire. . Once, of all things, my brother and I were stuck there for over an hour in our Jeep when we tried to pass through an arroyo that, for once, had water in it after a recent cloudburst. Considerably more than we had guessed. Our engine stalled with at least fifty feet of water on every side, in which, we were quite sure, we could see swimming snakes. Climbing over the vehicle, opening up the hood, and trying to dry the engine involved acrobatic skills that would have impressed any observer, had there been one.

These were vivid personalities, and they remain vivid in my memory — although that memory will fade rapidly as my own generation passes. My experience is pretty much the same as that of hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of millions of others, living and dead. We all have loved ones. And we all lose them, unless or until we ourselves are lost. Personality is the most precious thing in the universe.

But the Restoration promises that the dead persist as more than mere fading memories. It declares that personality survives, that it is everlasting. Even more than that, it offers the hope that our relationships can be preserved and perfected, too.

“And that same sociality which exists among us here will exist among us there, only it will be coupled with eternal glory” (Doctrine and Covenants 130:2).

I look forward to getting to know my first grandchild, whose brief earthly sojourn in mid-2014 never allowed her even to leave the Florida hospital in which she was born. I want very much to meet her:

#GiveThanks

There is a song in the Latter-day Saint hymnal that, growing up, I thought pure corny sentimentality. I no longer do:

Oh, what songs of the heart

We shall sing all the day,

When again we assemble at home,

When we meet ne’er to part

With the blest o’er the way,

There no more from our loved ones to roam!

When we meet ne’er to part,

Oh, what songs of the heart

We shall sing in our beautiful home.

Tho our rapture and bliss

There’s no song can express,

We will shout, we will sing o’er and o’er,

As we greet with a kiss,

And with joy we caress

All our loved ones that passed on before;

As we greet with a kiss,

In our rapture and bliss,

All our loved ones that passed on before.

So I’m grateful, grateful beyond expression, for the hope of life everlasting and of the perpetuation of family and other relationships into the next world. On this Thanksgiving Day and every day. I’m thankful to God for the promises he makes:

So long thy power hath blest me, sure it still

Will lead me on,

O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till

The night is gone,

And with the morn those angel faces smile,

Which I have loved long since, and lost a while.