My wife and I attended a screening of Heart of Africa 2: Companions last night at the LDS Film Festival. It is, to some extent, a retelling of the story in the first Heart of Africa movie, but this time the story is told from the standpoint of the white American half of the service-missionary companionship, rather than from that of the black African missionary. Still, it depicts a culture and a missionary experience that could scarcely be more different from my own in German-speaking Switzerland. The film opens today (Friday) in several Utah theaters.

Here’s a blog entry that I posted last year about the first film of the pair:

“In Support of Heart of Africa“

***

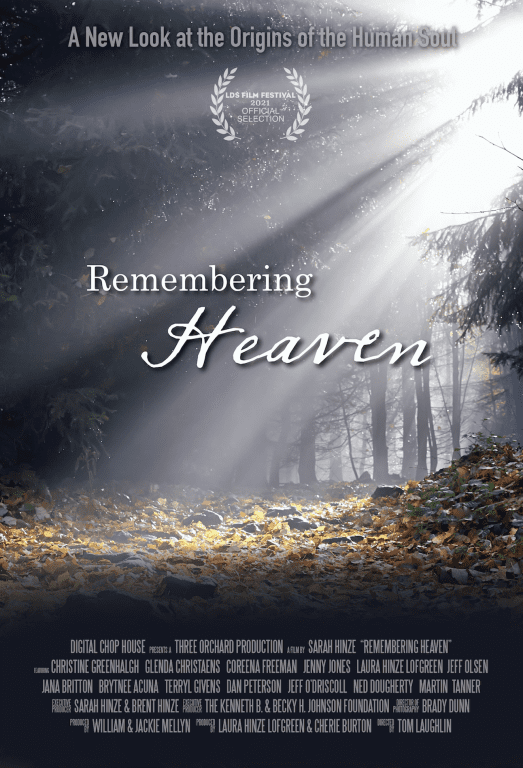

I’ll be spending part of today (Friday) with a couple of people that we are interviewing for our docudrama, Undaunted: Witnesses of the Book of Mormon, which we’re currently preparing for release, we hope and intend, on or near the date of the premiere of the Witnesses theatrical film. (And please remember that that premiere has now been set for Friday, 4 June 2021.) Then, assuming that we’re done in time, I hope to attend a screening at the LDS Film Festival of the new documentary film Remembering Heaven, which, among other things, includes interviews with both Terryl Givens and . . . well, another, rather seedier, academic type who shall remain nameless so as not to blight the film’s prospects of success.

You can read an article about Remembering Heaven at this link.

“Remembering Heaven: A New Documentary about Pre-mortality”

And you can watch the trailer for the film here:

***

I have recently read Things Fall Apart, which was written in 1958 by the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe (1930-2013). I’ve owned a copy of it, and I’ve been meaning to read it, for a very long time. Finally, I did. And, like Heart of Africa, it gave me a glimpse of a world quite unlike my own and yet, in several ways, not so very different from mine. I really do believe that novels and short stories written from within a different culture — the stories of the late Egyptian writer Yusuf Idris (1927-1991) come to mind, for example, along with such works as the “Cairo Trilogy” and the novel Midaq Alley by the Egyptian Naguib Mahfouz (1911-2006), who won the 1988 Nobel Prize for literature — can supply readers with a much deeper understanding of that foreign culture, certainly a very different understanding, than can large volumes of sociology and anthropology.

One very shallow and superficial matter for which Things Fall Apart made me grateful is the variety of food that’s available to pampered modern Americans like myself. In just the past few days, I’ve had Mexican food and Thai food, a large variety of fruits and berries, milk and cheese, almond milk, a bit more chocolate than I should have, fish, chicken, beef, wheat and oats and bread, vegetable soups, and on and on and on. By contrast, for Achebe’s characters, living in a few small Igbo or Ibo villages under British colonial rule (at first so distant as to be unfelt and then, rather suddenly, very much not), it’s almost entirely yams — with the occasional bit of palm wine to wash them down. And I don’t even like yams.

But on to a trio of passages from Chinua Achebe’s novel that I marked in passing:

Behind them was the big and ancient silk-cotton tree which was sacred. Spirits of good children lived in that tree waiting to be born. On ordinary days young women who desired children came to sit under its shade. (46)

That, of course, accords nicely with the theme of the film Remembering Heaven.

Have you not heard the song they sing when a woman dies?

“For whom is it well, for whom is it well?

There is no one for whom it is well.” (135)

That passage caught my attention because it sounds the theme that every life is touched by sorrow. All human relationships end with death, if not before. Few people exit this life feeling entirely complete or fulfilled, “no song unsung, no wine untasted.”

The missionaries had come to Umuofia. They had built their church there, won a handful of converts, and were already sending evangelists to the surrounding towns and villages. That was a source of great sorrow to the leaders of the clan, but many of them believed that the strange faith and the white man’s god would not last. None of his converts was a man whose word was heeded in the assembly of the people. None of them was a man of title. They were mostly the kind of people that were called efulefu, worthless, empty men. The imagery of an efulefu in the language of the clan was a man who sold his machete and wore the sheath to battle. Chielo, the priestess of Agbala, called the converts the excrement of the clan, and the new faith was a mad dog that had come to eat it up. (143)

Reading this, I could not help but think of the experience of many Latter-day Saint missionaries, myself included, and of scriptural passages like 1 Corinthians 1:26-29:

For ye see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called: But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; and base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are: That no flesh should glory in his presence.

See, too, 1 Nephi 8:26-27 and 1 Nephi 11:35-36.

(Achebe was himself the son of devoutly Christian-convert parents, but he fleshes out his description of the early converts to Christianity as being of lower social status on pages 155-157 of the novel, in his brief account of the osu, or outcasts, and their entry into the church in Umuofia.)

The page references above are to Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (New York: Anchor Books, 1994). I found the novel quite interesting, and, after all this time, well worth the time.