***

The news, when it first arrived early Friday afternoon, was uncertain. But it’s now clearly and sadly true: D. Michael Quinn, the well-known historian of the early Restoration and of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has died. He became a controversial figure, and he wasn’t especially fond of some of the things that I had written about his work. But he was always interesting, and I still remember when I first encountered his writing. I found it fascinating, and exciting. I wish all the best for him and for those he has now left behind.

***

***

I spent most of yesterday in meetings regarding, first, the approaching premiere of the Witnesses theatrical film — which will open in Utah and certain other movie houses at 7 PM on Thursday, 3 June, with an official opening on the following day, Friday, 4 June — and, second, the way we plan to configure the 3-5-minute short features or “snippets” to which we’ll shortly be turning some of our attention. I also devoted three hours to filming an interview with a scholar for inclusion in either the “snippets” or the docudrama or both. That, and grading my very last student papers, explains why this blog entry is late.

***

After beginning my freshman year at Brigham Young University as a mathematics major, I changed my focus — no doubt to the great but curiously unexpressed joy of my parents — from mathematics to a major in classical Greek with a minor in philosophy. I’ll probably comment further on that matter at some future point. For my current purposes, though, it will suffice to say that I graduated with a degree in Greek after several years of classes in Greek language and literature. Along the way, I became aware of the Loeb Classical Library, which I still to this day consider one of the greatest publishing projects I’ve ever encountered. It is a substantially complete collection of virtually the entirety of classical Greek and classical Latin writing, in dual-language Greek/English and Latin/English editions. Genuinely remarkable.

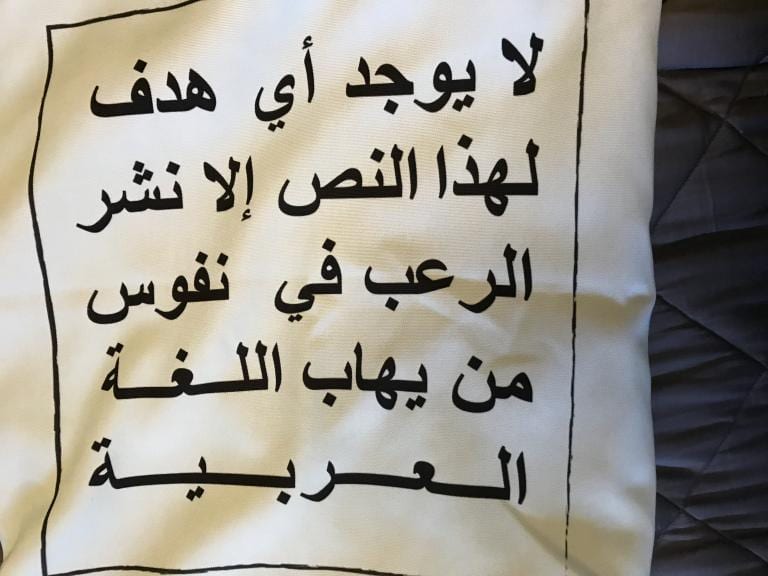

But when, after I had graduated from BYU with my degree in Greek (and philosophy), I moved over to Arabic studies, one of the things that I noticed right away was the lack of an Arabic equivalent, or an Arabic and Persian equivalent, of the Loeb Classical Library. What that meant was that, unless people had grown up knowing Arabic or Persian or had spent years mastering them in academic settings, most works of classical Islamic literature and science and so forth were utterly closed off to them. And I began to notice general histories of science that minimized Muslim contributions to scientific fields, and that sometimes went so far as to declare that the Muslims had contributed essentially nothing — and that contained not a single Arabic title in their bibliographies. The same was true for general histories of philosophy. The Arabs, they would often say, had simply inherited Greek philosophy and then passed it on to the Latin West, without making any important contributions of their own. But how, I wondered, could they possibly make such a judgment? After all, their bibliographies contained no evidence of reading in the Arabic sources, and the Arabic sources hadn’t been translated.

Candidly, it left me feeling just a bit indignant.

But then I realized that the problem wasn’t the fault of non-specialist historians of science, medicine, mathematics, and philosophy that they weren’t in a position to render valid judgments about the contributions of the Islamic world. It was the fault of the specialists in Near Eastern studies, who had not given them the tools — the translations — that would have permitted them to make such judgments.

So, I began to think, an Arabic or Arabo-Persian or Islamicate analogue to the Loeb Classical Library would be a wonderful thing. Arriving on the faculty of BYU, though, I didn’t really give the matter much more thought. Somebody ought to establish such a publication series. Obviously. But that somebody certainly wouldn’t be me.

And then, one day in the early 1990s, I received a phone call from the late Elder Alexander Morrison, a former academic and a member of the Seventy. He wanted to know whether there might be a time that we could meet at BYU. He was hoping to discuss ways in which the University could help to build relations with the Muslims and to build relations with the Islamic world, ways that would not be available to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as such. We spoke for several hours, discussing a number of possibilities. Perhaps my favorite among them, in a sense, was the hypothetical establishment of an endowed chair of Islamic studies. After all, I was, at that point, probably the most obvious candidate for such a chair, for the simple reason that I was pretty much the only candidate available. But I couldn’t in good conscience recommend going that route, because having a Latter-day Saint teach about Islam couldn’t always be guaranteed to please Muslims. (Latter-day Saints aren’t always pleased by what non-LDS scholars say about us.). Given his own background, we also spoke about humanitarian projects in and with the Muslim world. And, in fact, Church has been engaged in such projects for many years now, to (for what little it’s worth) my very great satisfaction.

The idea that really captured his interest, however, was my suggestion of a dual-language translation series that would permit the Islamic world to speak for itself. Such an idea, we reasoned, carried few if any downside risks, and it would be an obviously solid and fully legitimate academic undertaking. He took that proposal back to the First Presidency and the Twelve, whom he had been representing in our conversation, and they approved it. I should undertake such a project they said, offering no financial support. It was an unfunded mandate.

To be continued.

***

In my Wednesday blog entry, “Derek Chauvin and I,” I said that the subject needed to be approached “honestly and without demagoguery.” On one predictable message board, predictable folks are reacting to what I said with predictable dishonesty and demagoguery. Consider me astonished.