I had a lot of work to do yesterday, so we got outside much later than I had hoped. Still, we did manage to see a multitude of elk, several bison (including a relatively newborn calf), and a black bear; to spend some very peaceful time looking over Flood Geyser (which kindly staged a small eruption for us at the end) and the Midway Geyser Basin; to explore Firehole River and Firehole Lake; to relax for a while along the Madison River; to take in an obligatory eruption of Old Faithful; and to admire an absolutely gorgeous sunset. Time very well spent.

I also did some relevant reading yesterday, and I thought that I would share these two passages with you:

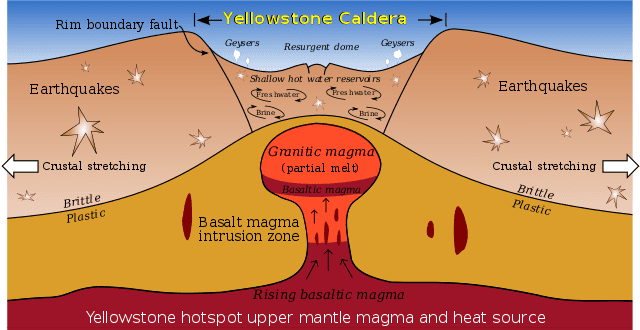

America’s oldest and most famous national park sits atop one of the largest, most explosive volcanoes ever to exist.

We can only imagine the explosion at what we now call Yellowstone National Park. No one witnessed it. It happened 2.1 million years ago. We are left to estimate its power by mapping exposures of welded tuff and studying strata of ash beds in far-flung reaches of the West.

But scientists have concluded that the eruption was immense, the energy released unfathomable — 2,500 times greater than the explosion that ripped Mount St. Helens in 1980, blowing off 1,300 feet of mountain, killing fifty-seven, and destroying forests for miles around eastern Washington. The Yellowstone eruption ejected more than a hundred times as much magma and ash as did Krakatau in Indonesia in 1883, when more than 36,000 died as a result of one of the most famous volcanic eruptions ever. Yellowstone — and a few other known volcanic eruptions — are termed “super volcanoes.” That means they have expelled at least 1,000 cubic kilometers (about 240 cubic miles) of magma more or less all at once. No volcano in historic times, when literate humans were around to witness it, has even approached such magnitude.

But humans may get a chance to see Yellowstone blow firsthand. Because Yellowstone is not only the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions ever known. It is also the largest, potentially most explosive, most violent, most deadly active volcano on the planet. Scientists say the chance of another catastrophic explosion someday is almost inevitable. . . .

When such an explosion occurs, it will be a catastrophe. Christiansen calls it a potential “major human disaster” — not just for the park but for the entire region. The park itself will be destroyed, the forest leveled, and every living thing within vaporized, incinerated, blown to bits, buried in welded ash and mud, or asphyxiated by carbon dioxide. People in the surrounding towns of West Yellowstone, Gardiner, and Cooke City will face the same fate. Towns and cities throughout the West will have to dig out from deep volcanic ash. Cars, buses, planes will all be grounded till the ash clears. Respiratory illness will soon take a toll. Domestic livestock and wildlife west of the Mississippi will be st[r]uck, and probably doomed. Great Plains wheat fields, the global breadbasket, will miss a season — or several — leading to widespread famine. The global volcanic winter will last years and influence the climate for decades or centuries. The worldwide death toll, says Michael Rampino, New York University associate professor of earth and environmental sciences, could reach a billion. “How do you get food, how do you get supplies, how do you get in and out, even after the eruption?” says Rampino, who has studied the climatic effects of huge volcanoes. “It depends on what you mean by killed — killed right away, starved to death?”

So we have something to look forward to — a probable disaster of global proportions. The question is when.

What is tantalizing — and a bit alarming — to consider is the timing of Yellowstone’s super eruptions: 2.1 million years, 1.3 million years, 640,000 years ago. The intervals are 800,000 and 660,000 years. That suggests another explosion is due — and, in geologic time, soon!

Meanwhile, the geysers vent, the hot springs bubble, and the fumaroles hiss, powered by the magma beneath the ground, by the same magma that has charged the largest active volcano on earth and one of the largest volcanic eruptions ever to rock the planet. They remind us that the monster still stirs.

Greg Breining, Super Volcano: The Ticking Time Bomb Beneath Yellowstone National Park (Beverley MA: Voyageur Press, 2007), 16-17, 20-21.

Just to make sure that words like something to look forward to and tantalizing, not to mention that final chirpy exclamation point (“soon!”), don’t get you to feeling too happy or positive, Breining’s epigraph is taken from George Gordon, Lord Byron’s, aptly named poem “Darkness”:

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went — and came, and brought no day.

The moral of the story, I suppose, is that you should come and visit Yellowstone National Park while it’s still here and while you’re still able.

Posted from West Yellowstone, Montana

There’s an irony here: The overwhelming majority of Yellowstone National Park is located in Wyoming. But the money-machine tax-revenue-generating tourist town of West Yellowstone is just over the state border in Montana. Life isn’t fair.