***

When I get too sleepy to read while I’m inflight on international trips, which I usually start sleepy because of packing but also because of long lists of last-minute things to do, I watch movies. It’s a good opportunity to catch up on movies that I haven’t seen and to review movies that I haven’t seen in a long time. I watched several films on my long recent flights from Salt Lake City to Minneapolis/St. Paul to Paris to Cairo and from Cairo to Paris to Atlanta back to Salt Lake City. Including at least two or three that were billed “classics.” Several of them were either quite good or quite interesting or both.

One of them was Walt Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia — a true classic that, during a theatrical reissue when I was a teenager, played a major role (along with my magnificent high school German teacher, Lenore Smith) in creating my love for classical music.

Watching Fantasia this time through, a line jumped out at me from Deems Taylor’s introduction to Igor Stravinski’s The Rite of Spring:

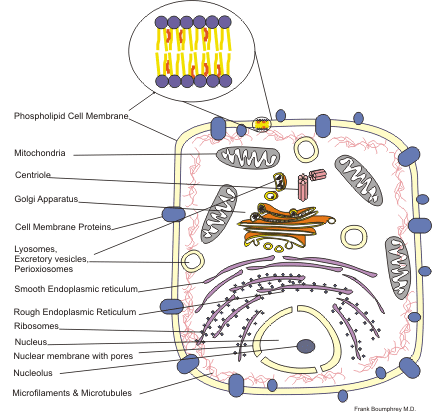

According to science, the first living things here were single-celled organisms, tiny little white or green blobs of nothing in particular that lived under the water.

“Little . . . blobs of nothing in particular”? Really?

Maybe that really was the view of science in 1940. Years ago, my late friend Frank Salisbury, who taught plant physiology for several decades at Colorado State University and then at Utah State University, told me that, when he was a doctoral student at the California Institute of Technology, they knew very little about plant cells. Such cells, he said, were regarded as pretty much just gobs of goo.

Well, things seem to have changed a bit since then. I quote here Michael Denton (M.D., Bristol University; Ph.D., King’s College London), but I don’t believe that what he has to say on this point is especially controversial now:

Molecular biology has shown that even the simplest of all living systems on earth today, bacterial cells, are exceedingly complex objects. Although the tiniest bacterial cells are incredibly small, weighing less than 10-12 gms, each is in effect a veritable micro-miniaturized factory containing thousands of exquisitely designed pieces of intricate molecular machinery, made up altogether of one hundred thousand million atoms, far more complicated than any machine built by man and absolutely without parallel in the non-living world.

Denton speaks of a

recently revealed world of molecular machinery, of coding systems, of informational molecules, of catalytic devices and feedback control.

See Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis (Bethesda, MD: Adler and Adler, 1985), 250, 271.

“Little . . . blobs of nothing in particular,” indeed.