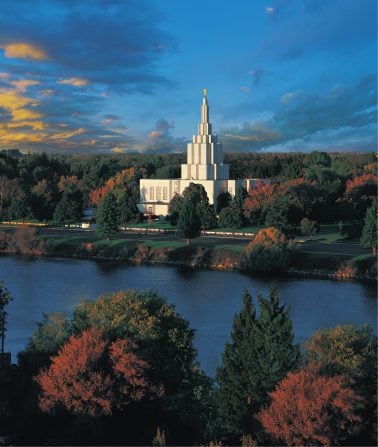

(LDS Media Library)

***

For something that I’m writing, I read a 2016 article today entitled “Living and Traveling in the Arab and Moslem Worlds” that was written by my longtime BYU colleague Professor Chad F. Emmett, of the Department of Geography at Brigham Young University: Chad F. Emmett, “Living and Traveling in the Arab and Moslem Worlds,” The Arab World Geographer / Le Géographe du monde arabe 19: 3-4 (2016).

Professor Emmett begins his article with a quite negative account of the Palestinian Arab city of Nazareth that was written by a nineteenth-century traveler. A former missionary in Indonesia who went on to study Arabic and who has since traveled extensively in the Islamic world, Professor Emmett himself spent (and enjoyed) a year in Nazareth doing research for his University of Chicago doctoral dissertation. And then he closes his article with this comment, with which I heartily concur:

As a 19th-century pilgrim who also visited Nazareth and had little positive to say, Mark Twain once wrote: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime” (Innocents Abroad).

***

Tonight, I read Henry B. Eyring, A Sacred Place Like This (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2021). It’s a very short book and very small, and it consists mostly of (beautiful) photographs of temples. At the very beginning of the book, President Eyring recalls an experience from his youth:

I recall the first day I walked into the Salt Lake Temple. I was a young man. My parents were my only companions that day. Inside, they paused for a moment to be greeted by a temple worker. I walked on ahead of them, alone for a moment. . . .

I looked up at a high white ceiling that made the room so light it seemed almost as if it were open to the sky. And in that moment, the thought came into my mind in these clear words: “I have been in this lighted place before.”

gfBut then immediately there came into my mind, not in my own voice, these words: “No, you have never been here before. You are remembering a moment before you were born. You were in a sacred place like this.” (3, 6)

President Eyring’s recollection resonates powerfully with me, because I had a somewhat similar experience many years ago, probably when I was about fourteen or fifteen. I’ve never forgotten it.

I was visiting Idaho Falls for the first time, I think with my brother and his wife. (If I’m correct, it was the time that they took me with them on a long loop trip up through Utah, the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, Glacier National Park, Banff and Jasper, and then down home to California via Olympic National Park in Washington. I fell in lifelong love with those places on that trip.) We stopped to walk around the temple grounds in the late summer evening, and it grew dark.

In those days, at least, the entrance to the temple consisted of a large area of clear glass, through which someone standing outside could see back to what I now know must have been the recommend desk. I was intrigued, I confess, by a place to which I could not be admitted, and I looked long and curiously at what I could see through the glass. I had just begun to develop an interest in, and a young testimony, of the Gospel. What was this place about?

I saw men and women, all dressed in white, silently passing back and forth before my eyes within this brilliantly illuminated and, to me, mysterious edifice. And suddenly it seemed very familiar, although I had never previously been in Idaho Falls. Not, at least, since I was a very, very small child on the way to Yellowstone with parents — one an inactive Latter-day Saint and the other a nonmember — who almost certainly wouldn’t have stopped to visit the temple there but would have simply passed on through. I seemed to remember having been in some such place before, a place that was full of light, quiet and deeply serene, holy, with people dressed in white. I felt as if I were looking into heaven. I’ve never forgotten that piercing and entirely unexpected sense of déjà vu, and I can certainly appreciate what the young Henry B. Eyring felt in the Salt Lake Temple.

***

The thirteenth-century poet Jalal al-Din Rumi is not only one of the greatest figures in the history of Persian literature but one of the very greatest of all Sufi mystics — Sufism being the mystical tradition in Islam. And Coleman Barks, who teaches poetry at the University of Georgia, has become a premiere Western interpreter of Rumi’s work.

I quote here from Coleman Barks, trans., The Essential Rumi (Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books, 1997), some passages illustrating Rumi’s belief — rare but not wholly unknown among classical Muslim writers — in the antemortal existence of the human soul or spirit. Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to fully reproduce Barks’s formatting:

Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?

I have no idea.

My soul is from elsewhere, I’m sure of that,

and I intend to end up there.

This drunkenness began in some other tavern.

When I get back around to that place,

I’ll be completely sober. Meanwhile,

I’m like a bird from another continent, sitting in this aviary.

The day is coming when I fly off . . .

Who looks out with my eyes? What is the soul?

I cannot stop asking.

If I could taste one sip of an answer,

I could break out of this prison for drunks.

I didn’t come here of my own accord, and I can’t leave that way.

Whoever brought me here will have to take me home. (2)

Another passage uses the image of a reed flute, with its plaintive sound, to talk about our finding ourselves “strangers and foreigners” in this fallen world, still vaguely aware that our true home is elsewhere:

Listen to the story told by the reed,

of being separated.

“Since I was cut from the reedbed,

I have made this crying sound.

Anyone apart from someone he loves

understands what I say.

Anyone pulled from a source

longs to go back.

At any gathering I am there,

mingling in the laughing and grieving,

a friend to each, but few

will hear the secrets hidden

within the notes. No ears for that.” (17-18)