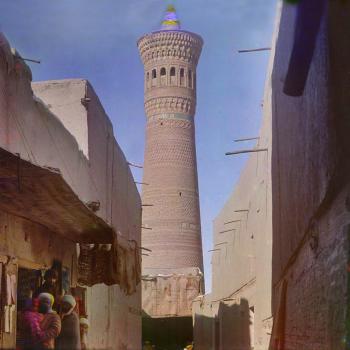

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

***

Two new pieces went up today in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship. The second offers a concise summation of the first:

“Serpents of Fire and Brass: A Contextual Study of the Brazen Serpent Tradition in the Book of Mormon,” by Neal Rappleye

Abstract: The story of the Israelites getting bitten in the wilderness by “fiery serpents” and then being miraculously healed by the “serpent of brass” (Numbers 21:4–9) is one of the most frequently told stories in scripture — with many of the retellings occurring in the Book of Mormon. Nephi is the first to refer to the story, doing so on two different occasions (1 Nephi 17:41; 2 Nephi 25:20). In each instance, Nephi utilizes the story for different purposes which dictated how he told the story and what he emphasized. These two retellings of the brazen serpent narrative combined to establish a standard interpretation of that story among the Nephites, utilized (and to some extent developed) by later Nephite prophets. In this study, each of the two occasions Nephi made use of this story are contextualized within the iconography and symbolism of pre-exilic Israel and its influences from surrounding cultures. Then, the (minimal) development evident in how this story was interpreted by Nephites across time is considered, comparing it to the way ancient Jewish and early Christian interpretation of the brazen serpent was adapted over time to address specific needs. Based on this analysis, it seems that not only do Nephi’s initial interpretations fit within the context of pre-exilic Israel, but the Book of Mormon’s use of the brazen serpent symbol is not stagnant; rather, it shows indications of having been a real, living tradition that developed along a trajectory comparable to that of authentic ancient traditions.

“Interpreting Interpreter: Ancient Fiery Serpents,” by Kyler Rasmussen

This post is a summary of the article “Serpents of Fire and Brass: A Contextual Study of the Brazen Serpent Tradition in the Book of Mormon” by Neal Rappleye in Volume 50 of Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship.

The full article can be read at https://interpreterfoundation.org/serpents-of-fire-and-brass-a-contextual-study-of-the-brazen-serpent-tradition-in-the-book-of-mormon/.

An introduction to the “Interpreting Interpreter” series is available at https://interpreterfoundation.org/interpreting-interpreter-on-abstracting-thought/.

***

Here are some striking statements — anyway, they strike me — from the late Charles H. Townes (1915-2015), who, after winning the 1964 Nobel Prize for Physics, was affiliated for many years with the University of California at Berkeley:

“At least this is the way I see it. I am a physicist. I also consider myself a Christian. As I try to understand the nature of our universe in these two modes of thinking, I see many commonalities and crossovers between science and religion. It seems logical that in the long run the two will even converge.”

“Many have a feeling that somehow intelligence must have been involved in the laws of the universe.”

“I strongly believe in the existence of God, based on intuition, observations, logic, and also scientific knowledge.”

“Science has faith. We make postulates. We can’t prove those postulates, but we have faith in them.”

Dr. Townes believed that “science and religion [are] quite parallel, much more similar than most people think and that in the long run, they must converge.” “Science,” he wrote, “tries to understand what our universe is like and how it works, including us humans. Religion is aimed at understanding the purpose and meaning of our universe, including our own lives. If the universe has a purpose or meaning, this must be reflected in its structure and functioning, and hence in science.”

“He was one of the most important experimental physicists of the last century,” Dr. Reinhard Genzel, himself a professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley, remarked upon the death of Dr. Townes at the age of 99.5. “His strength was his curiosity and his unshakable optimism, based on his deep Christian spirituality.”

“Scientists come in two varieties, hedgehogs and foxes. I borrow this terminology from Isaiah Berlin (1953), who borrowed it from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus. Archilochus told us that foxes know many tricks, hedgehogs only one. Foxes are broad, hedgehogs are deep. Foxes are interested in everything and move easily from one problem to another. Hedgehogs are only interested in a few problems that they consider fundamental, and stick with the same problems for years or decades. Most of the great discoveries are made by hedgehogs, most of the little discoveries by foxes. Science needs both hedgehogs and foxes for its healthy growth, hedgehogs to dig deep into the nature of things, foxes to explore the complicated details of our marvelous universe. Albert Einstein and Edwin Hubble were hedgehogs. Charley Townes, who invented the laser, and Enrico Fermi, who built the first nuclear reactor in Chicago, were foxes.”

Freeman Dyson, “The Future of Biotechnology,” A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe (2007), 1.

***

Sometimes, honestly, there’s an element of desperation in simply trying to keep up with the horrors that continually tumble out of the overflowing Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File©. It’s a bit like trying to bail water out of a sinking boat. Or, maybe more aptly, it’s reminiscent of Mickey Mouse as the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” in the 1940 Disney film Fantasia. Here is a quintet of theism-driven abominations that should give thrill-seekers a deliciously terrifying shiver:

“‘Membership has its privileges’: 38 benefits of Church membership we may not think about”