***

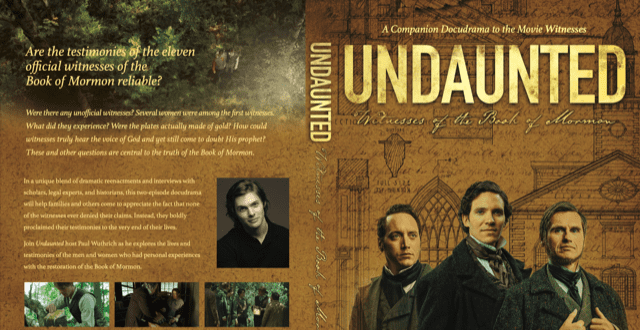

I would like to remind you of the premiere, this coming Friday evening — 4 March — of the Interpreter Foundation’s new docudrama Undaunted: Witnesses of the Book of Mormon. It will be shown as part of the 2022 LDS Film Festival at the SCERA Theater in Orem, Utah. Undaunted differs from the Witnesses theatrical film in several important respects. For one thing, it includes not only dramatic scenes (some borrowed from Witnesses, but others created especially for this new docudrama) but interviews with various subject experts, both Latter-day Saints and non-Latter-day Saints. For another, whereas Witnesses deals solely with the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon, Undaunted extends its coverage to the Eight Witnesses and to the informal or unofficial witnesses (e.g., Mary Musselman Whitmer).

Eventually, Undaunted will be available on DVD and via streaming (as Witnesses already is) in the form of a two-part docudrama that totals approximately 2.5 hours. (A special 90-minute director’s cut will be shown on Friday night, giving a substantial sense of both halves, along with a short feature and some material relating to our next film project.) We have never intended a theatrical release for Undaunted, so it’s very likely that this will be the only opportunity for most people to see the film on a large movie house screen.

Tickets for the premiere of Undaunted: Witnesses of the Book of Mormon are currently available from the 2022 LDS Film Festival, on its website.

***

I share here some passages from a book by Alister McGrath — an Anglican priest who holds three Oxford doctorates: a D.Phil. in molecular biophysics, a D.D. in theology, and a D.Litt. in intellectual history, and who currently occupies the Andreas Idreos Professorship of Science and Religion at the University of Oxford. It’s entitled The Big Question: Why We Can’t Stop Talking about Science, Faith and God (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015). He is both prodigiously talented and remarkably prolific, and I admire his work very much:

Science is wonderful at raising questions. Some can be answered immediately; some will be answerable in the future through technological advance; and some will lie beyond its capacity to answer — what my scientific hero Sir Peter Medawar (1915-87) referred to as “questions that science cannot answer and that no conceivable advance of science would empower it to answer.” What Medawar has in mind are what the philosopher Karl Popper called “ultimate questions,” such as the meaning of life. So does acknowledging and engaging such questions mean abandoning science? No. It simply means respecting its limits and not forcing it to become something other than science. (3)

He turns to the writing of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955):

Any philosophy of life, any way of thinking about the questions that really matter, according to Ortega, will thus end up going beyond science — not because there is anything wrong with science, but precisely because its intellectual virtues are won at a price: science works so well because it is so focused and specific in its methods.

Scientific truth is characterized by its precision and the certainty of its predictions. But science achieves these admirable qualities at the cost of remaining on the level of secondary concerns, leaving ultimate and decisive questions untouched.

For Ortega, the great intellectual virtue of science is that it knows its limits. It only answers questions that it knows it can answer on the basis of the evidence. . . . [Ortega:] “We are given no escape from ultimate questions. In one way or another they are in us, whether we like it or not. Scientific truth is exact, but it is incomplete.” (4)

McGrath himself is a former atheist. Here’s an autobiographical note:

So I embraced a rather dogmatic atheism, taking delight in its intellectual minimalism and existential bleakness. So what if life had to be seen as meaningless? It was an act of intellectual bravery on my part to accept this harsh scientific truth. Religion was just a pointless relic of a credulous past, offering a spurious delusion of meaning which was easily discarded. I believed that science offered a complete, totalized explanation of the world, ruthlessly exposing its rivals as lies and delusions. Science disproved God, and all honest scientists were atheists. Science was good, and religion was evil. (5)

[T]his “science versus religion” narrative is stale, outdated and largely discredited. It is sustained not by the weight of evidence but merely by its endless uncritical repetition, which studiously avoids the scholarship of the last generation that has undermined its credibility. . . . The “warfare of science and religion” narrative has had its day. (16, 20)

[T]he New Atheism prefers to ridicule religious people rather than engage seriously with religious ideas. Its rhetoric of dismissal allows it to present its ignorance of religious ideas as an intellectual virtue, when it is simply an arrogant excuse to avoid thinking. (20-21)

It is certainly true that science, if it is to be science and not something else, is committed to a method that is often styled “methodological naturalism.” That is the way that science works. That is what is characteristic of science, and it both provides science with its rigor and sets its limits. Science has established a set of tested and reliable rules by it investigates reality, and “methodological materialism” is one of them.

But science is about setting rules for exploring reality, not limiting reality to what can be explored in this way. It does not for one moment mean that science is committed to some kind of philosophical materialism. Some materialists argue that the explanatory successes of science imply an underlying ontological materialism. Yet this is simply one of several ways of interpreting this approach, and there are others with widespread support within the scientific community. Eugenie Scott, then director of the National Center for Science Education, made this point neatly back in 1993: “Science neither denies nor opposes the supernatural, but ignores the supernatural for methodological reasons.” Science is a non-theistic, not an anti-theistic, way of engaging reality. As the philosopher Alvin Plantinga so rightly observes, if there is any conflict between “science” and “faith,” it is really between a dogmatic metaphysical naturalism and belief in God. (19)

Слава Україні!