(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

***

We spent yesterday morning with friends looking around the Cathedral of Bordeaux — or, more precisely, the Cathédrale-Primatiale Saint-André de Bordeaux. Dedicated to St. Andrew the apostle, recognized by UNESCO for its importance and important position along one of the French pilgrimage routes to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela, and the seat of the archbishop of Bordeaux, the church, or anyway a forerunner, was first mentioned (so far as anybody today knows) in a document from the early ninth century. In 1096, it was formally consecrated by the French-born Pope Urban II, the very same pope who, in that very same year, launched the Crusades.

This is the cathedral in which Eleanor of Aquitaine (playing herself, not waiting to be portrayed by either Katharine Hepburn or Glenn Close) married Louis VII of France, some years before she went on to marry Henry II of England and to bear him, among others, Richard I (aka “Richard Cœur de Lion” or “Richard the Lionheart”) and John (Robin Hood’s evil Prince John, who later, as King John of England, was obliged by his unhappy barons to sign the Magna Carta at Runnymede, near Windsor).

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

In the afternoon, my wife and I joined a tour out to the small wine-producing village of Saint-Émilion, which is a roughly forty-five- or fifty-minute drive from downtown Bordeaux when the traffic is good. I wasn’t expecting anything. I hadn’t read a line about Saint-Émilion. But I was very pleasantly surprised.

First of all, the village is very pretty and quaint. Its varied elevations and overlooks and its narrow cobblestone streets are good enough for a Disney movie. And, although I’m a tee-totaling, fun-denying, faithfully observant follower of the Word of Wisdom, the beautiful vineyards that surround the town are the very quintessence of (my image of) French wine country. (Couldn’t they just repurpose them for the production of cheaper, more abundant red grape juice? I love red grape juice.)

What I found most interesting was the religious history of the village, which is named after a Breton monk called Émilion who settled in a hermitage carved into the rock there in the middle of the eighth century. Probably already by the time of his death in AD 767, other monks had begun to join him — so much for being a hermit! (rather like the original hermit, St. Anthony, in the eastern desert of Egypt) — and a community of them continued thereafter. In fact, since Saint-Émilion is located on the route of the Camino de Santiago (yes, that again), many monasteries and churches were built in it during the Middle Ages.

We visited the town’s parish church — visible in the photograph above — which is at least partially Romanesque, and thus probably dates to 1200 AD or before. But what was really astounding to me, partially because I didn’t expect it at all, was the village’s ancient monolithic or rock-hewn church which was carved into the side of the hill on which Saint-Émilion sits, out of a single block of stone. It is very large. Almost as large, I would estimate, as the parish church, which is not small. It was probably once rather brightly painted, but today only some faint outlines of saints and the Virgin and Christ himself are still visible if one looks very carefully.

Adjacent to the monolithic church is a multi-story catacomb, of which we visited only one level, the highest. The most striking feature of the catacomb, in my judgment, is a kind of tunnel in the ceiling that goes upward to the light. Speculation is that this was thought to symbolize the portal through which the souls of the deceased would travel toward heaven and into the next life. I wonder whether they had any notion of the tunnel that has been reported by so many near-death experiencers. Certainly such “tunnels” seem to have been known long before modern writers about NDEs began to discuss them. Hieronymus Bosch, for example, seems pretty clearly to have been aware of the concept in the early sixteenth century”

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Also adjacent to the monolithic church is the cell in which St. Émilion appears to have lived during his sojourn in the middle of the 700s AD. The woman who took us through the area called our attention to the baptismal font that it contained. She noted that there were stairs leading down into the font, which still to this day contains some water. Referring to the stairs, she explained that the saint, and others of his day, baptized the whole body of the new Christian convert by immersion. Not, she said, merely by sprinkling. That is a very weird concept, don’t you agree?

***

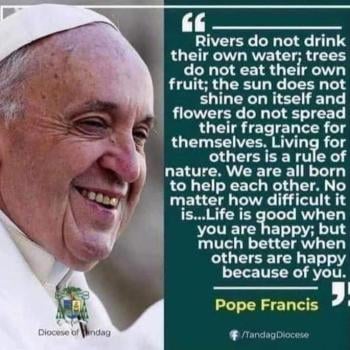

This essay offers some food for thought (I think):

***

Over dinner tonight, the conversation turned to people we’ve known who weren’t particularly sophisticated, or who had a difficult time with the Word of Wisdom or whatever, but who were reliably on the scene when service was called for — and how much we’ve come to admire such people and to hope the best for them.

I had one man particularly in mind. He sometimes worked for the construction company that my not-yet converted father and my never-a-member uncle founded and owned, and he was an adult convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (I expect that he’s been gone for decades, but I won’t name him because I don’t want to risk embarrassing his family.) He wasn’t a well-educated man. His grammar was poor, and I’ve sometimes joked, in recalling him to my wife and kids, that he had no idea at all where to locate 2 Nephi in the Old Testament. But even as a rather oblivious early teen, I noticed that he was the first to arrive at service projects and the last to leave, and that he was at every single such project in which I ever participated — and quite a few others besides. If there was a widow’s house to be fixed, he was there. Sometimes I was, too, but I had little to offer. I realized then that, while he was far from cultivated or urbane, and while I aspired in those days to be at least somewhat more cultivated and urbane than I was, he was worth minimally two of me. I was convinced then, and I’m convinced now, that he will occupy a wonderful place in the celestial kingdom. Me, though? Well, I can hope.

I was reminded of a quotation from the great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: “When I was young,” he once commented, “I admired clever people. Now that I am old, I admire kind people.”

Posted from the Atlantic Ocean, bound for Southampton, England