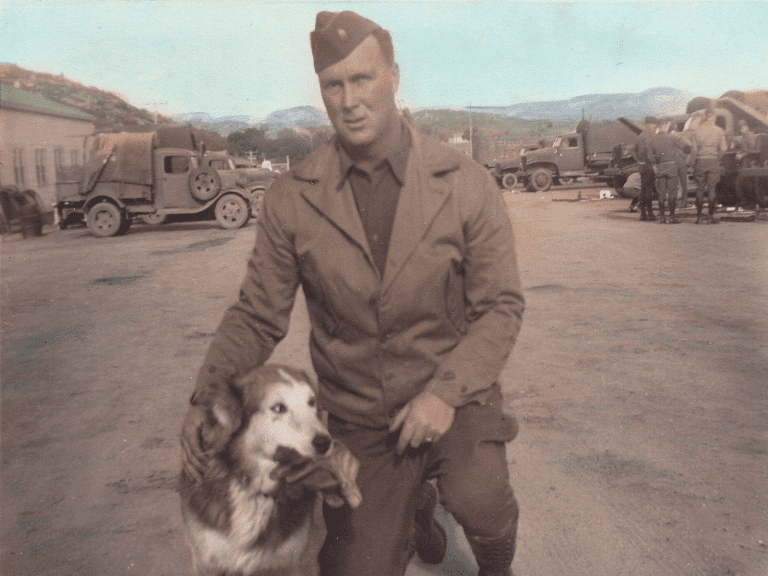

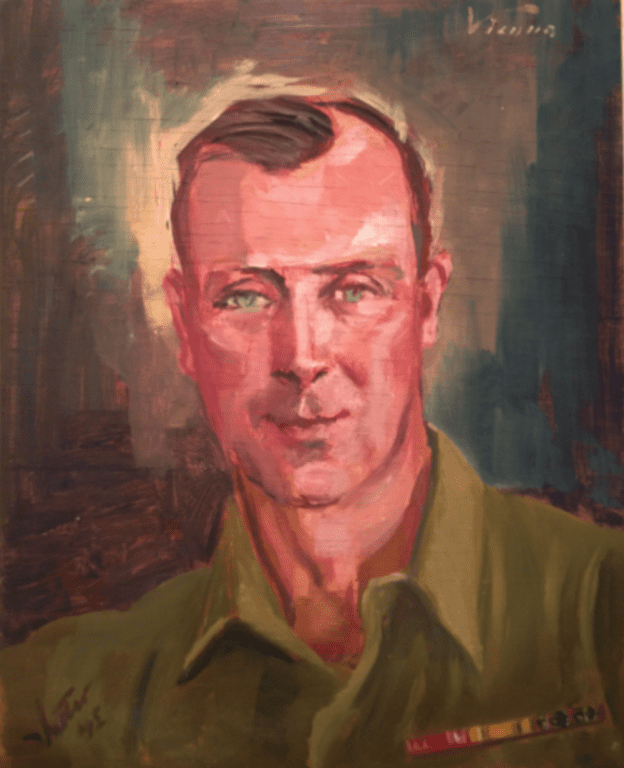

My father was born one hundred and nine (109) years ago today. He’s been gone now for somewhat more than nineteen years. But I’m thinking about him today, and I wanted to use this opportunity to commit a small handful of anecdotes about him to writing. As I’ve said on prior occasions here, this blog serves several functions, one of which is as an occasional venue for first drafts of my own life history and the story of my family.

For a part of the Second World War before he himself crossed the English Channel onto the European continent shortly after the D-Day invasion as part of General Patton’s Third Army, my father was stationed in High Wycombe. It’s a town in Buckinghamshire, England, nearly thirty miles (forty-seven kilometers) to the west northwest of London, slightly more than halfway to Oxford. High Wycombe is far enough out in the countryside that it wasn’t subjected to the V-1 and V-2 attacks that were terrifying London at the time, and my father was safe there.

But he wasn’t allowed to remain safe. He was a staff sergeant at the time, and one of the American captains assigned to High Wycombe regularly requisitioned him as a driver into London, where the V-1s and V-2s were raining down. Why? Because the captain, who had a wife back in the United States, was carrying on an affair with a female English military volunteer in the city. So my father was obliged to sit in London during the Captain’s adulterous trysts, under German assault. At one point, the captain was standing by a window in his love nest, looking out and smoking a cigarette, when a bomb or a rocket exploded nearby. The window shattered, and a shard of glass scratched his face. He received a Purple Heart for having been wounded by enemy action.

My father always lamented that he had never seen London at night with its lights on. It had always, of course, been under a blackout during his time there. We got him back to Europe more than once, but one of my dreams was to take him to England so that he could see London illuminated in the dark. Unfortunately, I never did. I regret that.

Incidentally, my father said that the V-1s were much more frightening, in a sense, than the V-2s were. The V-1 was subsonic, a primitive kind of cruise missile powered by a jet engine, and people below were painfully aware of it as it flew. (It was often nicknamed, for that reason, a “buzz bomb.”) In the perpetual London fog, above the clouds, you could hear it. Then, suddenly, it would run out of fuel, its engine would cut off, and those on the ground would know that it was falling. They just didn’t know where it would hit. And that, he recalled, was terrifying. By contrast, the much more advanced V-2 rocket, a ballistic missile, was supersonic. Which meant that you weren’t aware of it until it struck. It was terribly destructive, but there was no warning and, hence, in a way, no immediate apprehension.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

By the end of the war, my father was stationed in Le Vésinet, a suburb of Paris, where he waited to be demobilized. I’m not sure when he arrived there. V-E Day came on 8 May 1945. President Franklin Roosevelt had already died nearly a month before, on 12 April 1945. So I’m not sure whether my father was still in Gmunden, Austria, or whether he had arrived in Le Vésinet by then.

Anyway, when news of President Roosevelt’s death reached the troops in Europe, my father had been assigned to a barracks with several other non-commissioned officers. That evening, two of them were completely plastered, and they recruited a photographer who worked for the Army newspaper, The Stars and Stripes, to take pictures of them. They mugged for the camera, arms over each other’s shoulders, taking drunken pains to look deeply emotional in multiple poses, telling the photographer that these flash photos would make ideal illustrations for his paper, accompanied by the caption “American soldiers mourn the death of President Roosevelt.”

My Dad, watching the ridiculous spectacle, whispered to the photographer, “You’re not really wasting film on these two idiots, are you?” The photographer whispered back: “Are you kidding? Did you think I’d actually put film in the camera for this?”

Some years after the war, in the booming economy of southern California, my father and his brother launched a small construction company. And, along the way, he married the widowed woman from St. George, Utah, who would later become my mother. She already had a son, ten years my senior, from her previous husband, and, as she told me several times late in her life, one of the things that she most treasured about my Dad was the way he stepped into the role of father, and that he never showed any partiality for me over his stepson. And I can bear witness that it was true. We grew up always aware that we were half-brothers — he even retained his biological father’s surname — but we never felt that way. He was, simply, my older brother.

Our mother was a born storyteller, though, and she loved to tell stories about my Dad. Raised a Lutheran in North Dakota, he didn’t join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints until mid-1972. She liked to tell how, when she found him, he had been a drinker and a gambler. Which was actually true. In fact, he was so good at poker in his earlier years that, on one occasion in Las Vegas, when I was still fairly young, he won enough money to buy a nice piece of property right on the Colorado River, near Bullhead City, Arizona. He and his brother were planning to build some sort of very nice duplex on the property but, for some reason, they never did, and they eventually sold that parcel of land. (Another of my regrets.)

Moreover, her stories tended to get better with the passage of time. The gutter in which she found him became deeper and deeper over the years, the infrequent bottle of beer grew into near-alcoholism, his occasional gambling became habitual, and their meeting became a life-saving rescue. He would stand there while she told her tale with a beatific smile on his face. When asked why he was smiling, he would explain that he absolutely loved hearing these stories, because he always learned something new from them. Everybody would laugh, including my mother, and on things went.