(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

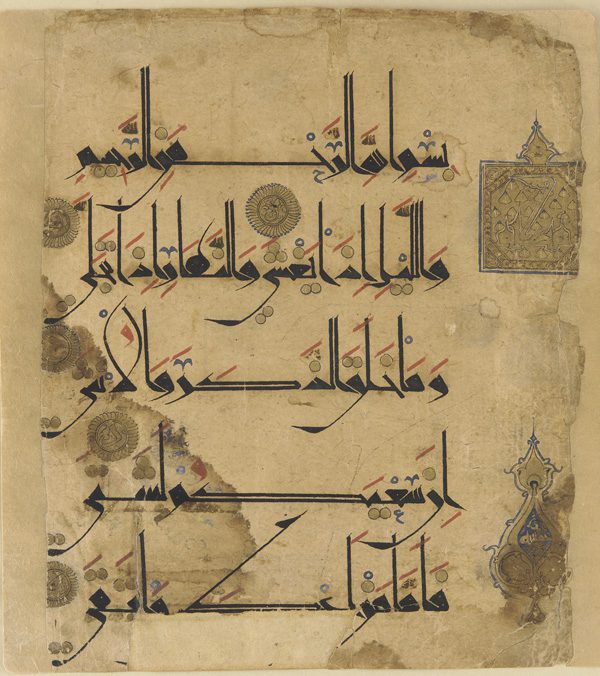

Preface: Kufic Arabic script is a style of writing the Arabic language. It originated very early — presumably in the city of Kufa, in Iraq — but it’s still sometimes used today. It features the same Arabic letters that are commonly used elsewhere in other script styles but, in Kufic, they’re elongated and angular. (See above.) This makes Kufic script especially well-suited for, among other things, monumental architectural inscriptions in stone.

Now to an anecdote:

Long ago, when my wife and I lived in Egypt, we often attended concerts and plays and lectures in Ewart Hall, on the old campus of the American University in Cairo that was located directly adjacent to Tahrir Square. AUC’s old campus is within walking distance of where I’m writing at this very moment; we actually drove past it a couple of times earlier today.

Above the stage in Ewart Hall was an inscription, in Kufic-style letters, that puzzled me for at least a year’s worth of attendance at events there. Maybe longer. I tried and tried and tried to read it, but I couldn’t recognize so much as a single actual word. This was profoundly discouraging to me, because it indicated that I had even further to go, in learning Arabic, than I had imagined.

And then, one evening, a spectacular realization came to me. I had been trying to read the inscription from right to left, because that’s the way Arabic script runs. Suddenly, though, it dawned on me that the inscription wasn’t even in Arabic at all. It was in stylized Roman letters that had been made to resemble Arabic script. In fact, it was in English — a language that I already knew fairly well by that point — and it ran, as English writing typically does, from left to right.

Once I recognized it as an English inscription, I could read it very easily. This is what it said:

“Let knowledge grow from more to more, but more of reverence in us dwell.”

It’s from the 1849 poem “In Memoriam A. H. H.,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892).

I’ve thought about this experience many times over the years. It illustrates, for me, the difficulty that we sometimes have in seeing things that we’re not expecting to see.

My efforts were bent so intensely on learning to read Arabic at the time that, as an overreaction, I tried to read an admittedly Arabic-looking text as if it actually were Arabic rather than my own native English.

I had an analogous experience on another occasion: I had been reading so much Arabic at the time, going from right to left, that, one day, while reading an English-language book and having just completed a page, I absentmindedly turned to the next page the way that I would do with an Arabic one. But the “next” page was a page that I had already read, and I thought that my book was defective, repeating pages. It took me surprisingly long — by which I mean several seconds — to see the stupid mistake that I had made.

But back to the first story, about that Tennyson inscription in Ewart Hall: Sometimes, we can’t see what’s clearly before our eyes because we’re so thoroughly certain of what we ought to be seeing. I think this an important point, with very wide application. Here’s a minor one:

My mother was a born storyteller, and she particularly loved to tell stories about my Dad. He had been raised a Lutheran in North Dakota, and he didn’t join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints until mid-1972, when he was in his late fifties. She liked to tell how, when she found him in the years following the Second World War, he had been a drinker and a gambler. Which was actually, technically, true. He occasionally drank a beer and, once in a while, he gambled. In fact, he was so good at poker in his earlier years that, on one occasion in Las Vegas, when I was still fairly young, he won enough money to buy a nice piece of property right on the Colorado River, near Bullhead City, Arizona. He and his brother were planning to build some sort of very nice duplex on the property but, for some reason, they never did, and they eventually sold that parcel of land. (Which I regret.)

Moreover, Mom’s stories tended to get better and better with the passage of time. The gutter in which she found him became considerably deeper over the years, the infrequent bottle of beer grew into stumbling near-alcoholism, his occasional gambling became habitual, and, well, their meeting became a life-saving rescue. He found this very amusing. He would stand there while she told her tale with a beatific smile on his face. When asked why he was smiling, he would explain that he absolutely loved hearing these stories, because he always learned something new from them. Everybody would laugh, including my mother, and on things went.

I feel somewhat the same way when I read threads on the Peterson Obsession Board in which earnest pseudonymous scholars of my thought endeavor to lay out my positions and to explain the motivations behind my vicious crimes, my absurd ideas, and my hilarious antics. On the whole, I seem to be a rather depraved, cruel, and corrupt dimwit (though at the same time, curiously and inadvertently, an often amusing one). Still, even I’m occasionally capable of learning new things, and I always learn lots of new things about what I believe and about what drives me when I read those threads — things that I had never so much as thought of until I read about them on the POB.

The wisdom of Jane Austen’s Mr. Bennet is perfectly apt here: “For what do we live,” he asked, rhetorically, “but to make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn?”

But so, too, is that inscribed quotation at the American University in Cairo. The little coterie of Peterson scholars at the POB badly want me to be a cruel buffoon and so, accordingly, that’s exactly what I am. Which is, umm, perhaps not wholly coincidental. Sometimes, unfortunately, “a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

Posted from Cairo, Egypt