As I write, there are only twenty-five shopping days remaining until Christmas. But I hope that, amidst all of the frenetic activity that precedes the biggest holiday of the year, we’ll all be able to find at least a little bit of time for reflection.

Here is something that I wrote for Christmas 2012. It hadn’t been a good year for me. In fact, it was the worst year of my life. Among other things, suddenly and without warning I had lost my brother, my only sibling, in March of that year. (We were unusually close; my parents were already gone.) And then, only three months later, after nearly thirty pleasant years that had been almost completely free of even the slightest whiff of academic politics, I ran, without forewarning, right into a life-altering concentration of such politics that more than compensated for the previous long interval of serene career satisfaction. And my mother in law was grievously ill with the disease that would take her life the following spring.

Now, re-reading the column below with the benefit of hindsight, I think that the previous months must have subconsciously influenced the approach to Christmas that I adopted in it:

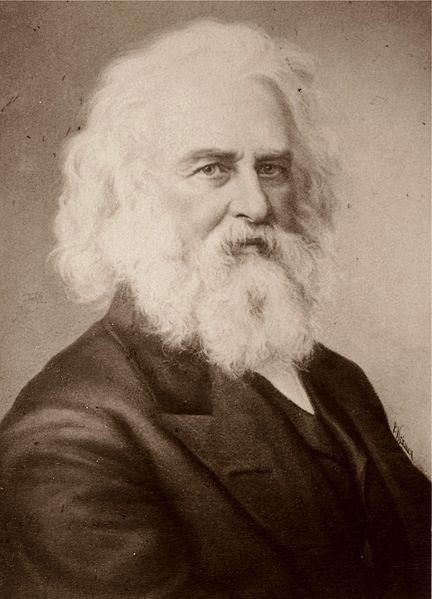

His first wife, Mary, died after a miscarriage. His second wife, Fanny, died in a freak household fire. Trying to save her, he himself was burned so badly that he couldn’t attend her funeral and, for the remaining decades of his life, couldn’t shave. His iconic image, still today, features a long white patriarchal beard.

“How inexpressibly sad are all holidays,” he wrote on the first Christmas after Fanny’s death. One year after her passing, he commented, “I can make no record of these days. Better leave them wrapped in silence. Perhaps someday God will give me peace.” His journal entry for 25 December 1862 reads: “‘A merry Christmas’ say the children, but that is no more for me.” Late in 1863, his eldest son, Charles, was severely wounded fighting for the Union in the American Civil War. Longfellow made no journal entry at all for Christmas that year.

“I heard the bells on Christmas Day,” he wrote on 25 December 1864. But the war still raged, and he was still in pain. “And in despair I bowed my head: ‘There is no peace on earth,’ I said. ‘For hate is strong and mocks the song of peace on earth, good will to men.” But then his mood shifted. “Then pealed the bells more loud and deep: ‘God is not dead, nor doth he sleep; the wrong shall fail, the right prevail, with peace on earth, good will to men.'”

Mere words are wholly inadequate in the face of great human suffering, brought home to us in an especially horrifying way by last week’s report from Newtown, Connecticut. However, the central idea of Christianity, which we celebrate at this very season, is that God hasn’t confined himself to mere words.

“The Word was made flesh,” reports John, “and dwelt among us.” And, therefore, “the Light shineth in darkness” (John 1:14, 5). The God of Christianity is no unmoved mover, no absentee landlord, distant and unfeeling—let alone a hanging judge, a kind of cosmic Inspector Javert. Describing the Savior’s response to the death of his friend Lazarus, John 11:35 is the shortest verse in scripture but among the most significant: “Jesus wept.” “Then said the Jews,” in the next verse, “Behold how he loved him!”

Christmas is a child’s holiday, a day of wonders for kids. But it’s infinitely more.

Almost a century before the Savior’s birth in Palestine, the New World prophet Alma explained that Jehovah would come to earth, among other reasons, “that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities” (Alma 7:12).

The Prophet Joseph Smith learned by revelation in 1832 that Christ “ascended up on high, as also he descended below all things, in that he comprehended all things, that he might be in all and through all things, the light of truth” (D&C 88:6).

There is no sorrow, no despair, no pain, no hopelessness that the Lord doesn’t know from direct experience. He didn’t just read about these things in a book.

In March 1839, Joseph Smith languished miserably in the jail at Liberty, Missouri, while his people, because of their trust in his teaching, were being driven from their homes during a brutal Midwestern winter. Seeking divine comfort, he was given an appalling list of sufferings and injustices and then gently reminded that “The Son of Man hath descended below them all. Art thou greater than he?” (D&C 122:8).

The comfort seldom comes instantly. “Thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment,” said a revelation to Joseph (D&C 121:7). However, they lasted more than five years, ending only with his death at the hands of a mob.

But Julian of Norwich, the early English mystic (d. 1416), was nonetheless right when, under inspiration (as she claimed), she summed up her Christian hope in the simple words “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

And this is true only because the Savior (Immanuel, “God with us”) came into the world. The light of Christmas shines even brighter after the darkness of Newtown. Because he lives, its victims shall live also. (See John 14:19.)

“And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away” (Revelation 21:4).

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I continue to be saddened by the passing of Kent Budge, who most recently posted comments here as dCyl. I valued his contributions on this blog and, as I continue to think about an eventual conference on science as a religious enterprise and experience, I would have valued his offered participation. Today, I received a kind note from his sister Lori, who included a link to his obituary. I had looked unsuccessfully for it earlier, and I think that some readers here might want to read it: https://rivera.mykeeper.com/family/KentBudge1/