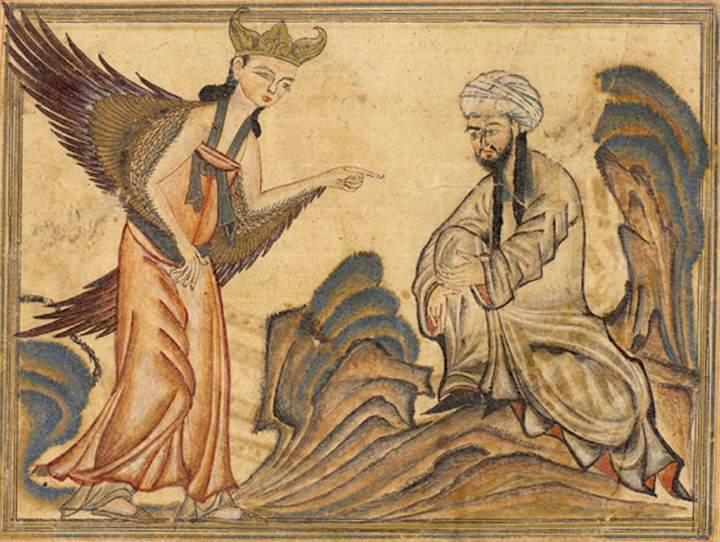

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

By now, you may perhaps have heard of this outrageous case from Hamline University in Minnesota. (I’ve already mentioned it here in my blog entry for 30 December 2022, noting that I myself have used precisely the same image — see immediately above — in lectures that I have delivered, accompanied by exactly the same explanation about varieties within Islam and about differences of Muslim opinion with regard to images of the Prophet Muhammad.) Here is an octet of articles that I’ve noted about the matter, in no particular order and with no claim or pretense to completeness:

National Review: “Old-World and New-World Illiberalism Team Up at Hamline University”

Amna Khalid, of Carleton College, in The Chronicle of Higher Education: “Most of All, I Am Offended as a Muslim: On Hamline University’s shocking imposition of narrow religious orthodoxy in the classroom”

Kenan Malik, in The Guardian: “An art treasure long cherished by Muslims is deemed offensive. But to whom?: An academic spat over a depiction of Muhammad reveals how the language of diversity is eviscerating its very meaning”

Christiane Gruber, Professor of Art, University of Michigan: “Islamic paintings of the Prophet Muhammad are an important piece of history – here’s why art historians teach them”

Jill Filopovic, in Slate: “Hamline University’s Controversial Firing Is a Warning: Insistence that others follow one’s strict religion is authoritarian and illiberal no matter what the religion is.”

Mark Silk, Professor of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College in Connecticut, where he also serves as the Director of the Leonard E. Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life: “Who says you can’t show students a portrait of Muhammad? A multiple-choice quiz to help college administrators navigate religious freedom on campus.”

“Hamline University under fire for art professor’s dismissal”

Hamline University’s administration should be ashamed of itself for its ignorant pandering, its gross injustice, and its crude violation of academic freedom, and it should reinstate Erika López Prater immediately and with (at the very least) an apology.

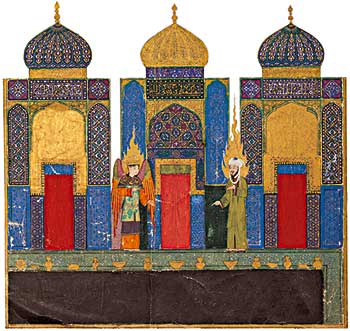

(15th cent Persian ms. Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

It is true that the Islamic artistic tradition has devoted far more attention to calligraphy and to more or less abstract representations than to, say, landscape painting or other forms familiar in the West. It has tended to shy away from portraiture, and especially from portraying saints and prophets. In particular, there has been, in many circles, a reluctance to depict the Prophet Muhammad. You will, so far as I’m aware — and I’ve been in more mosques than I can count — never, ever, see a portrait of Muhammad in a mosque, and certainly not in the specific space set aside for worship. Moreover, there are absolutely no “illustrated Qur’ans” in the manner of the illustrated Bibles, for both children and adults, with which many of us are well acquainted. Even when the Prophet is depicted, it is not uncommon for his general bodily form to be indicated while, at the same time, his face is either left blank or covered with a cloth veil. There is a real fear among many Muslims, both historically and still today, of falling into idolatry.

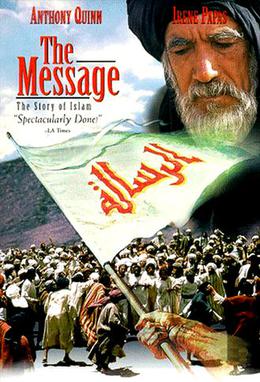

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Today, extreme sects of Sunni Islam — e.g., the Wahhabis of the Arabian Peninsula — are vociferous in their opposition to visual representations of the Prophet Muhammad. But, although they would fain claim that they speak for Islam as a whole, they don’t. Not historically and not today. And it seems inappropriate, to say the least, for the administration at an American university to give those extreme sects veto power over how Islam should be depicted and portrayed in the West and even, in a sense, over how other Muslims (a substantial minority, if not indeed the majority) express their own faith.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

A once-famous case of the reluctance to show Muhammad is the 1976 film by the Syrian-American director Moustapha Akkad entitled The Message (Ar-Risālah or الرسالة; originally, Mohammad, Messenger of God), which I saw when it appeared and remember quite liking. (Of course, I really liked Anthony Quinn.). Although it is a narrative of the life of Muhammad as seen from the perspective of his uncle Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib (played by Anthony Quinn) and his adopted son Zayd ibn Harithah, it never shows Muhammad himself. Rather, the camera is Muhammad, and we watch events unfold through his eyes.

But that is absolutely not to say that there is no artistic tradition among Muslims of representing the Prophet. In fact, I offer four examples of precisely that here in this blog entry — see above — and I could easily have multiplied them many times over.

It would be an oversimplification to say that such representations are characteristic solely of the Iranian and/or Shi‘i regions of the Islamic world (e.g., modern-day Iran and Afghanistan), but it wouldn’t be altogether misleading, either.