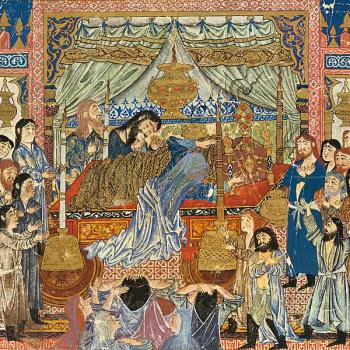

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

For reasons known only to me, although a couple of other folks might be able, if they put their minds to it even slightly, to divine my intent — is that mysterious enough for you? really, it’s no big deal — I have been gathering notes over the past few days on the topic of the biblical concept of “creation.”

And here is a portion, albeit only a small portion, of what I’ve written up on the topic over the past three or four days:

“Creation,” wrote the great scholar of comparative religions Mircea Eliade, is the pre-eminently divine act. As such creation accounts offer a rich trove of archetypes and understandings for the cultures that treasure them.[1]

I close with a quotation from Luis Stadelmann about the Hebrew Bible that could also mutatis mutandis have been written about the Qurʾān.

Within the account of the origin of the world we will discover a veritable philosophy of history designed to trace out the purpose of Yahweh from the very creation of the world to the settlement of his Chosen People in the land of Canaan. . . .

In order to promote the understanding that the world belongs to Yahweh, this theme of Yahweh’s ownership is mentioned again and again throughout the Bible. But once God had created the world, he did not leave it on its own by withdrawing his providential guidance. He continues to rule over this universe and provides for its best possible function. It is natural, therefore, that the universe should share with mankind the duty of proclaiming God’s praises. As a matter of fact, the universe seems to have its own life and stands over against Yahweh sufficiently to offer its praises, to act as witness against mankind, and to await in awful surrender the day of judgment.

On the basis of a group of passages which express the idea rather of divine activity than of a passive scene on which the universal history is depicted or of a stage on which God acts as sceneshifter, we are led to the conclusion that the universe is thoroughly alive, and, therefore, the more capable of sympathy with man and of response to the rule of its Creator on whom both man and universe directly depend. Certainly we have here more than a poetical personification of the cosmos when it is invited to rejoice. . . .

In fact, the universe is summoned to share in the religious adventure of humanity.[2]

But that is a story for another day. I can only hope that I can remain as productive into my retirement as Noel B. Reynolds has well into his.

[1] That is a principal theme of Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return: or, Cosmos and History, translated by Willard R. Trask (Princeton University Press, 1971). The specific quoted phrase occurs on page 11. We ourselves have inherited a culture dominated by neo-Darwinian accounts of creation, and they mark our culture in innumerable ways.

[2] Luis I. J. Stadelmann, The Hebrew Conception of the World, Analecta Biblica 39 (Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1970), 7-8. For summary remarks on God’s continuing involvement in nature according to the Hebrew Bible, see Georg Fohrer, Geschichte der israelitischen Religion (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co, 1969), 172-174.

It’s that throwaway comment from the first footnote — “We ourselves have inherited a culture dominated by neo-Darwinian accounts of creation, and they mark our culture in innumerable ways.” — to which I want to return.

I know how the entailments and implications differ between a view of origins that posits our having been placed here by divine power for a divine purpose and a view holding that we and the world in which we live are, at every level and to the farthest reaches of the cosmos, the result of random chance occurrences within environmental constraints directed to no conscious end.

What interests me here is the “trickle down” effect of each of the two distinct opinions. For they seem to me clearly to imply significant but potentially widely varying conclusions about the status and value of humankind, and to ground quite different views of such things as ethics and “human rights.”

What are the psychological effects of believing in the one, as opposed to believing in the other? How do the two broadly differing opinions affect the self-image of people who believe in one or the other? Or even of those who have simply come to maturity immersed in one or the other? Do they lead ineluctably (or, at least, commonly) to divergent Weltanschauungen — to divergent “worldviews,” though I do love that German word!

The term survival of the fittest was, I’ve been told, coined not by Charles Darwin himself but by an enthusiastic follower, the British philosopher Herbert Spencer. Spencer set forth what he thought were the social and economic implications of Darwinian thought. And his doctrine became known as “Social Darwinism.” It grounded a strong belief in, among other things, laissez-faire capitalism, most unregulated economic competition.

Another view, quite different from laissez-faire capitalism, became the official doctrine of the Third Reich. History was a battleground for survival, for resources and Lebensraum (living space) and dominance, between races. Adolf Hitler dismissed humankind as “a ridiculous cosmic bacterium” (ein lächerliches kosmisches Bakterium), and he believed that, in seeking to subject the world to Aryan rule, he was following the dictates of science.

I don’t intend to suggest here, by any means, that belief in a wholly naturalistic Neo-Darwinian view of life’s origin — and, prior to that, in a a completely naturalistic view of the beginnings of the universe, our solar system, and our planet — lead inescapably to either Nazism or Social Darwinism. (Though I’m not sure on what grounds a thorough-going naturalist can argue against somebody who devoutly believes in either of those possible options.) I am saying, though, that, just as Luis Stadelmann suggests in the passage that I quote above, within an account of the origin of the world we can surely discover a veritable philosophy of history.