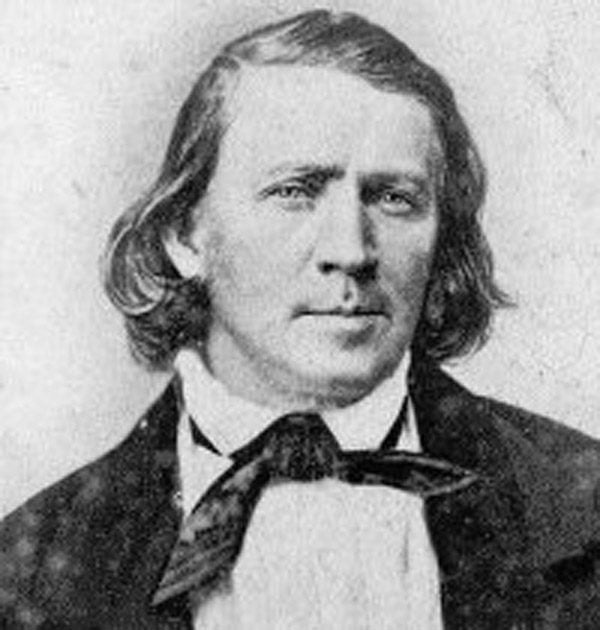

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

On a message board where harshly negative reviews of the Interpreter Foundation’s as-yet uncompleted film project Six Days in August have been pouring in by the dozens, appraisals of Brigham Young have also been abundant. Brigham was, it seems, not a decent man. Indeed, he was a frightening bully and a murderous tyrant.

One earnest soul even offers a reading list of contemporary nineteenth-century perspectives on President Young in order to support such judgments — contemporary sources, of course, being the historian’s gold standard — that runs the gamut of viewpoints ranging all the way from A to B: Wife No. 19: The Story of Ann Eliza Young; Bill Hickman’s Brigham’s Destroying Angel; Tell It All, by Mrs. T. B. H. Stenhouse; and The Rocky Mountain Saints, by T. B. H. Stenhouse himself.

It’s quite a list. A parallel case might be to accept at face value the claims of the “Copperheads,” the 1860s Democrats who supported the Union but opposed the Civil War, against Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant (aka “Grant the Butcher”), and accepting their position as The Truth© about Lincoln, Grant, the War, and the Emancipation Proclamation, which they also opposed. In LaCrosse, Wisconsin, Brick Pomeroy, the editor of the local Democrat newspaper, regularly called Lincoln the “widow maker” (when he didn’t use the term “orphan maker” instead), and advocated Lincoln’s assassination if the president chanced to be reelected. “This war is murder, & nothing else. And every man who gives a dollar or moves his finger to aid [it] is an aider & abettor of murder,” one New York Copperhead wrote.

On the day following the dedication of the cemetery at the Gettysburg battlefield, many of the nation’s newspapers reprinted President Lincoln’s remarks there, along with the much longer speech given by Edward Everett. And reaction to Lincoln’s address was typically (and predictably) divided along political lines. “The cheeks of every American,” said the Chicago Times, “must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances” of Mr. Lincoln’s now classic speech. The Harrisburg Patriot and Union wrote that “We pass over the silly remarks of the President; for the credit of the Nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.”

A basic understanding of the craft of historical analysis and writing might have taught The Earnest Soul mentioned above that, while contemporary sources are valuable, they still require weighing and evaluation. Contemporaries can be partisan and biased — and ignorant and foolish and dishonest — just as easily as later historians can be.

Stanley Baldwin, who served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from May 1923 to January 1924, from November 1924 to June 1929, and from June 1935 to May 1937, was indisputably a contemporary of Winston Churchill, but his declaration that Churchill lacked “judgement and wisdom” should perhaps not be taken as the final and entire truth of the matter.

The English novelist Evelyn Waugh, another contemporary, deeply disliked Churchill, and he included Churchill’s writing style in his comprehensive disdain: Churchill, said Waugh, was a “master of sham-Augustan prose” with “no specific literary talent.” J. H. Plumb, another contemporary of Churchill’s, described his prose style as “curiously old-fashioned and somewhat out of place, like St. Patrick’s Cathedral on 5th avenue.” And yet Winston Churchill won the 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature — not merely for his immortal wartime speeches but for such writings as The World Crisis, Marlborough: His Life and Times, his six-volume memoir, The Second World War — written, all 2.5 million words of it, while he was serving as the Conservative Party’s opposition leader in Parliament and then during his second tenure as prime minister of the United Kingdom — and the four-volume A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. The Nobel citation explained that Churchill was receiving the Prize in recognition of his “mastery of historical and biographical description,” as well as for his oratorical eloquence. Neither J. H. Plumb nor, perhaps unjustly, Evelyn Waugh ever won a Nobel Prize.

A full-orbed view of any given historical topic must pay attention to negative and critical accounts. Of course. But it isn’t obliged to give them full faith and credit.

So, do I have recommendations for books that I would place up against the books for which The Earnest Soul vouched? Yes, indeed I do.

One very enjoyable work that provides a strikingly different (and very funny) perspective on Wife No. 19: The Story of Ann Eliza Young is Hugh Nibley’s 1963 book Sounding Brass, which bore the subtitle Informal Studies in the Lucrative Art of Telling Stories About Brigham Young and the Mormons. It is now conveniently available along with Nibley’s equally hilarious 1961 book The Myth Makers in a volume of the Collected Works of Hugh Nibley that was published by Deseret Book and the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) in 1991, under the title of

Hugh Nibley, whose political views were (I should probably point out) considerably to the left of mine, was an enthusiastic fan of Brigham Young, about whom he also wrote at length in essays that were gathered in 1994 into the volume

Another seriously left-leaning admirer of Brigham Young — I mention their political viewpoints because, well, these are not people who would seem natural and particular admirers of a murderously tyrannical theocrat, a supposedly frightening bully, and they were both well known as mavericks and independent thinkers within the Church — was the late Eugene England, whose Brother Brigham I have praised and enthusiastically recommended in previous blog entries here.

Finally, for now, I commend to your attention Leonard J. Arrington’s Brigham Young: American Moses and Thomas G. Alexander’s

These are books about Brigham Young that have been on my mind of late. Of course, there are many more, and I will probably be making further recommendations in the months to come.