My mother grew up in St. George, and my ten-years-older brother was baptized in the St. George Utah Temple. The temple in St. George has long held a special place in my heart and soul; it played a particular role in the earliest stirrings of my own personal faith. And President Jeffrey R. Holland means a great deal to me (as he does to many others), so I was delighted for him that he was able to rededicate that temple today: “President Holland Rededicates His Hometown’s House of the Lord.” And please take the time to watch the eleven-minute video that is embedded in the article.

Once more (and it certainly won’t be the last time), I return to BYU Studies Quarterly 61/4 (2022), which is a special issue of the regular quarterly journal BYU Studies. It was produced by four faithful Latter-day Saint Egyptologists — Stephen O. Smoot (Ph.D. candidate, Catholic University of America), John Gee (Ph.D., Yale University), Kerry Muhlestein (Ph.D., University of California at Los Angeles), and John S. Thompson (Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania) — and it bears its own unique title: A Guide to the Book of Abraham. As I’ve explained previously, it represents something of a state-of-the-question survey from people who are thoroughly familiar with the topic and the issues. Moreover, and as I’ve also explained before, I am largely quoting bottom-line conclusions. I am not claiming to reproduce the evidence and the arguments on which those bottom-line conclusions are based. That evidence and those arguments are given in A Guide to the Book of Abraham itself, which I commend to your attention.

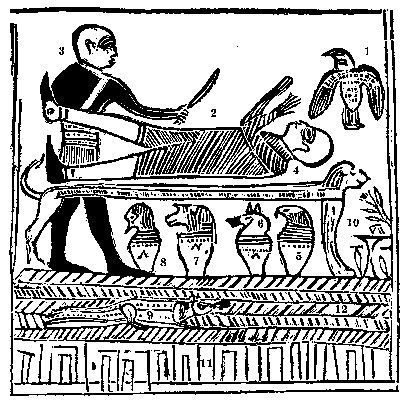

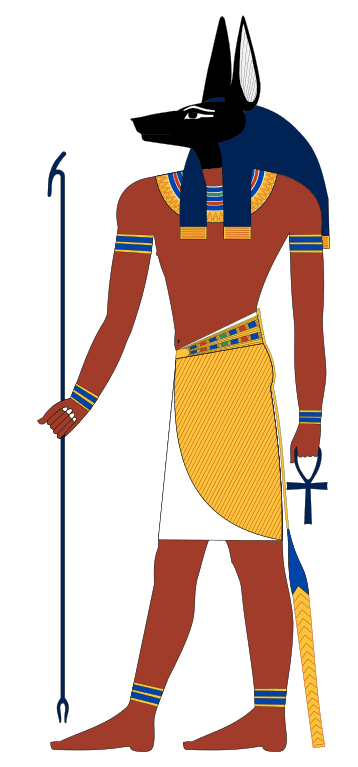

As I’ve already indicated, Part 3 of A Guide to the Book of Abraham (209-281) is devoted to “The Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham.” I want to share some passages from two parts of that section — “Facsimile 1 as a Sacrifice Scene” (221-225) and “The Idolatrous Priest (Facsimile 1, Figure 3)” (227-233) — that caught my attention. First, though, I need to note that the figure of the “idolatrous priest” shown in Facsimile 1, with his shaven head, is frequently assumed to represent a mistake made by Joseph Smith. His head is missing from the papyrus; after its loss, the head was restored by Joseph or by someone working under his direction. But it should, the critics say, rather have been the head of a jackal, the jackal-headed god Anubis. And he should not be holding a knife. Moreover, they say, the scene is not one of human sacrifice, but of embalming. More evidence that Joseph Smith was a fraud!

Since the mid-1800s, when Egyptologists first began analyzing the facsimiles of the Book of Abraham, Joseph Smith’s interpretation of this scene (sometimes called a lion couch scene, due to the prominent lion couch at the center of the illustrations) has clashed with Egyptological interpretations. . . .

From the weight of this Egyptological opinion, it may seem strange to associate Facsimile 1 with sacrifice as Joseph Smith did. However, more recent investigation has turned up evidence that suggests a connection between sacred violence and scenes of the embalming and resurrection of the deceased (or the god Osiris). (221-222)

After a brief survey of this “more recent investigation” (with abundant references in the footnotes), the authors observe that,

From this and other evidence, it can be seen that at least some ancient Egyptians associated scenes of the resurrection of Osiris with the slaughter of enemies. (223)

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image, created by Jeff Dahl)

So what about the “idolatrous priest” or Anubis?

Commenting on this passage, Egyptologist Mark Smith observes that in this [first-century papyrus] text “the embalming table [the lion couch] is also a judge’s tribunal and the chief embalmer, Anubis, doubles as the judge who executes sentence. For the wicked man, mummification, the very process which is supposed to restore life and grant immortality, becomes a form of torture from which no escape is possible.” That Anubis had a role as judge of the dead, besides merely being an embalmer, has previously been acknowledged by Egyptologists.

One task Anubis fulfilled with this role was as a guard or protector who “administer[ed] horrible punishments to the enemies of Osiris.” (224)

The authors don’t claim to have entirely disposed of the objection, but they certainly seem to feel that recent research has considerably weakened it:

Nor is it to suggest that these parallels are perfect matches for how Joseph Smith interpreted this scene. Rather, it is to say that “excluding a sacrificial dimension to lion couch scenes” or scenes depicting the mummification of Osiris, which is how Egyptologists have interpreted Facsimile 1, “is un-Egyptian, even if we cannot come up with one definitive reading [of Facsimile 1] at this time.” (225, quoting John Gee)

And what about the human-headed “idolatrous priest” with his knife?

At least two different nineteenth-century eyewitnesses who examined the papyri [presumably prior to the loss of the papyrus fragment containing the head of the figure -dcp] . . . reported seeing “a Priest, with a knife in his hand” or “a man standing by [the figure on the lion couch] with a drawn knife.” The significance of this is that the presence of a knife in the original papyrus “has here been described by . . . eyewitness[es] whose description of the storage and preservation of the papyri matches that of independent contemporary accounts. . . . This gives us two independent eyewitnesses to the presence of a knife on Facsimile 1, regardless of what we might [otherwise] think.” As such, despite what some scholars assume should be on the original papyrus, “it is not valid to argue that something does not exist because it does not correspond to what we expect.” [228, quoting from John Gee]

The two independent witnesses, by the way, were the faithful Latter-day Saint William I. Appleby (1811-1870), who died in Utah territory, and the avowedly anti-Mormon missionary and clergyman Rev. Henry Caswall (1810-1870), who did not.

Furthermore, the crescent shape of the knife in figure 3’s hand is consistent with the shape of ancient Egyptian flint knives that were used in ancient Egypt for, among other activities, “ritual slaughter” and execration rites. Indeed, “killing involving flint [knives] is connected in myth to sacramental killings, killings involving the restoration of order and the defeat of evil.” The mythological and practical significance of the flint (or sometimes obsidian) knife as a means of both destroying evil through execration rituals and preparing the deceased for embalming (which in some ways were conceptually linked in the minds of some ancient Egyptians) appears to have survived into the Ptolemaic Period. This strongly reinforces the likelihood that the knife was original to the scene. (228-229)

Such Egyptian use of flint knives over the centuries reminds me of the commandment given to Joshua and the Israelites, as recorded in Joshua 5:2-5, which is just one occurrence of flint knives in such a biblical context:

2 At that time the Lord said to Joshua, “Make for yourself flint knives and circumcise again the sons of Israel the second time.” 3 So Joshua made himself flint knives and circumcised the sons of Israel at Gibeath-haaraloth. 4 This is the reason why Joshua circumcised them: all the people who came out of Egypt who were males, all the men of war, died in the wilderness along the way after they came out of Egypt. 5 For all the people who came out were circumcised, but all the people who were born in the wilderness along the way as they came out of Egypt had not been circumcised. (New American Standard Bible)