The other day, here on this blog, I posted an appreciation of Walt Disney and of the Walt Disney Company that he founded slightly more than one hundred years ago in Los Angeles, California, on 16 October 2023. Rather mysteriously, it was titled “In praise of Disney.”

The immediate impetus for my post wasn’t Disney’s centenary but, rather, the fact that some of us had, in company with the principal locus of Cuteness in the western United States, been watching a run of classic Disney cartoons (e.g., Bambi, Cinderella, and Beauty and the Beast). For a couple of nights, being in a location from which we were basically unable to access Disney movies, we took a break from late-night Disney cartoons and, instead, watched the 2021 animated adventure comedy film Back to the Outback and then, the next night, the 2021 Sino-American animated fantasy comedy film Wish Dragon. We quite enjoyed both of them, and, most importantly, I’m pleased to report that they were well received — nay, enthusiastically received — by the unsleeping Cuteness Itself.

Last night, though, as soon as we were able, we were back to Disney. We watched Sleeping Beauty, and the older ones among us were reminded all over again how very good it is. The Unbearable Cuteness of Being loved it, too, and, in fact, joined spontaneously in the waltz of Prince Phillip and Princess Aurora (aka Briar Rose) that is featured in the film’s closing scene.

Wikimedia Commons public domain

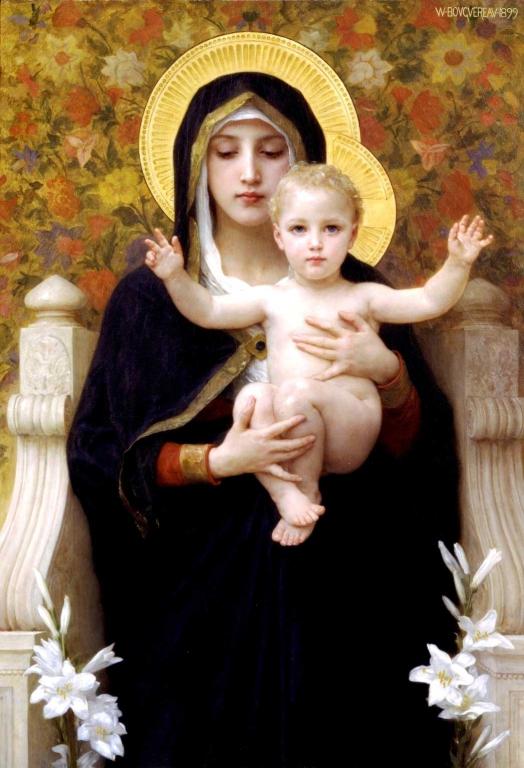

I suspect that veneration of the Virgin Mary reflects not only her own greatness but a dimly perceived ancient theological truth.

- Latin text

- O magnum mysterium,

- et admirabile sacramentum,

- ut animalia viderent Dominum natum,

- jacentem in praesepio!

- Beata Virgo, cujus viscera

- meruerunt portare

- Dominum Christum.

- Alleluia.

- English translation

- O great mystery,

- and wonderful sacrament,

- that animals should see the new-born Lord,

- lying in a manger!

- Blessed is the Virgin whose womb

- was worthy to bear

- Christ the Lord.

- Alleluia!

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

My sadly departed friend Bill Hamblin and I published the following column in the Deseret News for 22 December 2017. I hope that you’ll find it of interest:

The English word “Christmas” — “Christ’s mass” — reveals the holiday’s Catholic origin. With the coming of the Protestant Reformation, though, many Catholic practices and traditions were rejected or at least abandoned.

How did Christmas survive the Protestant purge? In some places, it nearly didn’t.