(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

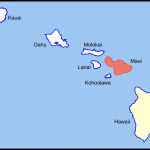

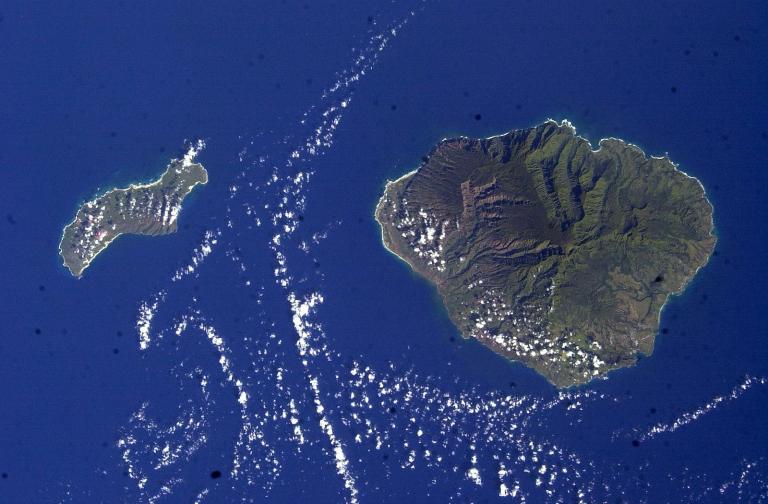

Traveling around Hawai’i — we went up and around to Princeville today, and out to the overlook by Kilauea Point Lighthouse — it’s interesting to see evidences of the forces that made its islands and that are now, in most places here, very slowly unmaking them. As the tectonic plate on which the Hawaiian Islands sit, the Pacific Plate, moves to the northwest at an annual rate of about 2.75 inches or seven centimeters — they leave behind them the stationary “hot spot” that formed them. Kaua’i and O‘ahu and the other islands age and begin very slowly to decay under the onslaught of rain and wind and — far and away the most important factor — under the relentless, never-ceasing pounding of the Pacific Ocean. Kaua’i — often called “The Garden Isle” — is the oldest of the significant tourist islands, geologically speaking. Necker Island, located about 430 miles northwest of Honolulu, rose at one point about 3300 feet above the ocean and was roughly the size of today’s O’ahu. Today, it’s little more than a rocky ridge. Its highest point is roughly 277 feet above sea level, its length is 0.8 miles, and its width at its very widest point is well under seven hundred feet.

Kaua’i, long since volcanically quiescent, is very gradually approaching the fate of Necker Island. The resorts here will no longer be available for vacationing at that time; Lilikoi’s will no longer offer its excellent mahi-mahi fish and chips. Maui’s western volcano is scarcely recognizable as a volcano any more, except to an observant geologist or the occasional visiting geek like me who likes to read about local geological features while on vacation. Its eastern volcano, Haleakalā, is dormant. However, it still rises to more than ten thousand feet, and it’s still thought capable of erupting even now; its last recorded eruption occurred in 1790, which is, in geological terms, the merest blink of an eye.

But the real geological vitality in Hawai’i today continues in and near the southeastern-most of the islands, the so-called “Big Island,” which is itself named Hawai’i. Anybody who was paying attention to the news at that time will be aware of the fact that Mauna Loa erupted in November and December of 2022, and that Kilauea is erupting as I write. Further, underwater and offshore to the south southeast of the Big Island is the active volcanic seamount formerly known as “Lōʻihi.” In 2021, in its wisdom, the U.S. Geological Survey adopted for it, instead, the more ambitiously Hawaiian name of “glowing child of Kanaloa,” or Kamaʻehuakanaloa. (Kanaloa is the Hawaiian god of the ocean.) Somewhere between ten thousand years from now and a hundred thousand years from now, Kamaʻehuakanaloa will emerge above the surface of the Pacific Ocean. That’s probably sufficient time for real estate salespeople and condo developers to devise a way of dealing with its somewhat unwieldy new name. Perhaps, taking a cue from Jennifer Lopez, it can be K-Loa. (Can I collect royalties on that name?)

I suppose that my overall meditation is this: In my ever-advancing old age, as people who meant a great deal to me and whom I love have passed on, the sentiment expressed in the hymn has come to mean more and more to me:

Abide with me; fast falls the eventide;

The darkness deepens; Lord with me abide.

When other helpers fail and comforts flee,

Help of the helpless, O abide with me.Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim; its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see;

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

If there is anything at all that could be termed a “terrestrial paradise,” I suppose that the Hawaiian Islands might come close. They are very beautiful. Their climate is delightful. Their breezes are (mostly) gentle. They are, today, fertile and rich with life. Even Mark Twain, a notable cynic, was deeply moved by them:

“No alien land in all the world has any deep strong charm for me but that one, no other land could so longingly and so beseechingly haunt me, sleeping and walking, through half a lifetime, as that one has done. Other things leave me, but it abides; other things change, but it remains the same. For me its balmy airs are always blowing, its summer seas flashing in the sun; the pulsing of its surfbeat is in my ear, I can see its garlanded crags, its leaping cascades, its plumy palms drowsing by the shore, its remote summits floating like islands above the cloud wrack; I can feel the spirit of its woodland solitudes, I can hear the splash of its brooks; in my nostrils still lives the breath of flowers that perished twenty years ago.”

But the Hawaiian Islands are unstable. Biology and geology have taught us that there is nothing immutable here on earth, and Hawai’i is one of our planet’s most obviously mutable locations.

The Hawaiian paradise began as barren volcanic rock emerging from the sea. It will end as barren volcanic rock crumbling into the sea. In the meantime, human corruption exists here just as it exists everywhere else. (Have you really never seen Hawaii Five-O?). And sickness and death are present here, as well. We passed at least two old cemeteries along the road to Princeville. The serpent has long since entered the Garden.

There is no earthly paradise. Not yet, anyway.

And there is no natural paradise in outer space. Pre-Copernican astronomy assured us that, in the superlunary world, beyond the sphere of the moon, all was changeless perfection. Orbits were perfect circles, the crystalline spheres were made of a perfectly transparent celestial element, a quintessence unlike the four changeable elements familiar to us here below. But Galileo and comets and sunspots changed all that.

Our hope for paradise must be fulfilled elsewhere, or not at all. As the author of the epistle to the Hebrews put it, speaking of the ancient saints:

13 All these people died in faith without receiving the promises, but they saw the promises from a distance and welcomed them. They confessed that they were strangers and immigrants on earth. 14 People who say this kind of thing make it clear that they are looking for a homeland. 15 If they had been thinking about the country that they had left, they would have had the opportunity to return to it. 16 But at this point in time, they are longing for a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore, God isn’t ashamed to be called their God—he has prepared a city for them. (Hebrews 11:13-16, Common English Bible)

Posted from Līhuʻe, Kauaʻi, Hawai’i