I want to share a few more passages that I marked during my recent reading of Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847-1862 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022).

It seems that the Saints in Utah were, by and large, unsympathetic to slavery

The presence of the enslaved in the Latter-day Saint settlements had caused discussion and dissent, but only fragments of the settlers’ reactions remain in the historical record. (87)

Frances [sic] and Margaret Lockhart McKown left for Utah Territory with two enslaved people, but Margaret died on the way, and after Francis discovered the extent of antislavery sentiment in the territory, he returned to Mississippi. (59)

[W]ithin a few years, most Mississippi enslavers left for California or returned to the South. (61)

They [the extended Greer family, from Texas] planned to take the four enslaved members of the Camp household with them, but one of them, Daniel, did not want to return to slavery in the South. He ran away, and an ad hoc slave patrol hunted him down. Among those who were shocked at this evidence of Southern slavery was Bishop Edwin D. Woolley, a former Quaker from Pennsylvania. He had the four Southerners arrested and charged with kidnapping. The judge eventually threw out the case for lack of evidence, but Daniel remained in Utah. (26)

In 1859, Horace Greeley, the famous editor of the New York Daily Tribune, visited Utah Territory and interviewed Brigham Young. In the course of the interview, Greeley asked whether Utah planned to be a slave state. “No,” Brigham replied, “she will be a Free State.” He proceeded to explain that “Slavery here would prove useless and unprofitable. I regard it generally as a curse to the masters. . . . Utah is not adapted to Slave Labor.” (26)

It may or may not be relevant to note that some of the enslavers – notably Thomas S. Williams – “change[d] from devout Latter-day Saints to outspoken opponents of Brigham Young’s control over the economics and politics of Utah Territory.” (89)

And there are other indicators of attitudes toward Blacks and toward slavery on the part of Latter-day Saint leaders and future leaders:

Scottish immigrant and later Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Charles W. Nibley worked for Bankhead after he arrived in America. He recalled that his employers were the wealthiest in the area. “Among other property, they owned two men negroes, Nate and Sam.” He explained, “It seems like harking a long way back to the days of slavery, but negro slavery was actually the law of the land and practiced to a small extent in 1860 and 1861 and 1862 in Cache Valley.” Nibley continued, “I felt quite elated when I could sleep with big Nate, the big black negro that Bankhead owned. Old Sam used to ask me if I had read any news of ‘de wah,’ and I can remember very well him saying at one time, ‘My God, I hope de Souf get licked.’” He concluded, “Only once did I see the old man Bankhead get angry at his slaves, and at that time he tore around pretty lively and threatened to horsewhip them to death if they didn’t mend their ways.” A violent threat almost too ordinary to be mentioned in Southern memoirs was still memorable to Nibley seventy years later. (94)

In 1855, Latter-day Saint apostle Orson Hyde traveled to Carson Valley as its probate court judge. His first criminal case was that of a Black man named only as Thacker, who had threatened to cut out and roast the heart of Sophronia Allen Rose. Fearing that the community would lynch Thacker, Hyde arrested him, fined him court costs, and suggested that for his own protection, he should join his unnamed enslaver in California. “Thacker” may be Robert Thacker (1832-) of Tennessee, who worked five years later as a waiter in Marysville, California.

Although Latter-day Saints were the first to build towns in the area, the 1860 census shows a predominantly non-Latter-day Saint mining population. . . . The census does not specify legal status, and none of the Black or interracial families appear to be connected to the Latter-day Saint settlers. (331)

But let’s look at the one significant law passed by the territorial legislature of “Deseret” with regard to the regulation of slavery within its jurisdiction. It reveals both what we would regard as Brigham Young’s problematic though paternalistic racism (and Orson Pratt’s “impassioned” opposition to slavery) and a seeming intent of mitigating or even gradually ending slavery within its jurisdiction:

Utah Territory . . . instituted a curious legal hodgepodge called An Act in Relation to Service (1852), identified by legal scholar Christopher B. Rich Jr. as patterned on the gradual emancipation laws of the Northeast or Midwest, rather than the slave codes of the South. The Act attempted to treat slavery as contracted labor and provided unusual legal protections, including a requirement that labor could only be sold with the consent of the “servant.” (12; compare 16)

In 1852, in the wake of unrest involving the Indigenous and Mexican slave trade, the territorial legislature crafted legislation and held a debate over African American slavery. Despite impassioned opposition from Latter-day Saint apostle Orson Pratt, Brigham Young supported legislation allowing Black servitude. In a speech to the legislature, he identified the origins of slavery and race in the Bible. He said that those of African descent were created for service, but if slavery was practiced, it should be practiced humanely, since Southern slavery abused principles set forth in scripture. With Young’s support, the territorial legislature codified and regulated African American sales and servitude. Young’s explanations to the legislature and in other settings not only ensured the passage of the Act but also began a practice that prevented most Black members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from holding the lay priesthood or participating in temple rites for more than a century.

An Act in Relation to Service attempted to shift chattel slavery into a system of contracted labor. It decreed that those who took “servants justly bound to them, arising from special contract or otherwise,” into the territory “shall be entitled to such service or labor by the laws of the Territory.” Those taking “servants” into the territory must register “written and satisfactory evidence [in the probate court] that such service or labor is due.” The Act limited the term of service for “servants” and their children to the time required to fulfill “the debt due his, her, or their master or masters.” It forbade sexual intercourse between the enslaver / and enslaved or indentured of African descent, or any “white person” and “any of the African race.” Although an Act in Relation to Service prohibited sexual relations between Black and White and enslavers and enslaved, it did not specifically prohibit interracial marriage. Those with “servants” must “correct and punish . . . when it may be necessary” and must provide for those in their service, including food, clothing, recreation, and at least eighteen months of education between the ages of six and twenty years. (18-19)

The law forbade enslavers from sexual abuse or rape. Enslavers had to provide the enslaved with “reasonable hours” of work, along with “comfortable habitations, clothing, bedding, sufficient food, and recreation” and refrain from cruelty or physical abuse. Enslavers were obliged to provide eighteen months of school prior to the twentieth birthday. Any punishment should be “reasonable” and “guided by prudence and humanity.” If not, a probate judge could remove an enslaved person from a household (90).

Another way of looking at the Act is that it attempted to move some distance toward reducing the distance between slavery, on the one hand, and, on the other, indentured servitude and apprenticeship — which we today would probably also regard as oppressive and tyrannical. Moreover,

Perhaps by design, An Act in Relation to Service gave Brigham Young the ability to emancipate Green Flake and others left in the valley when their enslavers went to California in 1851. (19; compare 112, 113-114)

There are indicators, too, of Brigham Young’s concern about the status of unmarried enslaved people in the Salt Lake Valley (83).

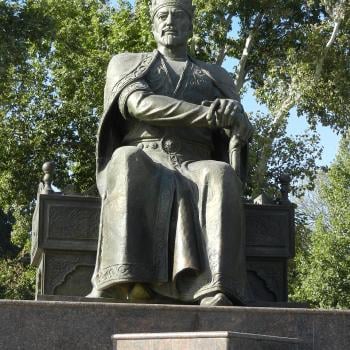

(Photo by Ryan Reeder at the English language Wikipedia)

In this context, I think it worthwhile to revisit something about which I posted here nearly three years ago:

In his important book Religion of a Different Color, Paul Reeve recounts an interesting episode involving Brigham Young:

An early mixed-race (Black and American Indian) member of the Church named William McCary — a rather marginal, somewhat erratic, and even unbalanced fellow, as it turned out, who ultimately and lamentably didn’t remain in the Church — had encountered racial prejudice among some Church members.

In response to this, President Young counseled the Saints to “use the man with respect.” (The verb to use is employed here in a somewhat archaic sense common in Shakespeare. See below. In today’s English, we would use the verb to treat.)

But some problems persisted. And Brother McCary continued to complain.

Was he in some way sub- or even non-human?

“Its nothing to do with the blood,” replied President Young, “for of one blood has God made all flesh.”

Professor Reeve comments on this exchange:

It was an echo of the same New Testament verse (Acts 17:26) that [Joseph] Smith quoted in his presidential platform three years earlier. Both drew upon the Bible to assert a broad commonality among humankind and were simultaneously acknowledging a wider racial debate then animating the scientific and Christian communities. In paraphrasing Acts 17:26, Young and Smith were referencing an important verse then commonly cited among nineteenth-century Christians. Believers used the verse to defend against a polygenesis theory then stirring scientific arguments about the origins of the various races. Scientists who promoted the polygenesis theory believed that there were multiple independent creations rather than just a single biblical creation. Each creation gave rise to a new race, which meant that whites and blacks were in fact from different species. Even though the two species could biologically reproduce, one argument was that an innate repugnance against interracial mixing was intended to preserve ‘species distinction.’ Those who violated the innate repugnance were really violating nature, which was a sure sign of their moral degradation. Physical degeneracy followed and within a few generations the offspring of such unions would be sterile.

[See W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 128-131.]

It’s become fashionable in recent years to demonize Brigham Young as a racist, even a vicious one — and, in some cases, essentially to forget that there was anything else to the man.

I resist this.

He wasn’t perfect, of course. Nor has any subsequent apostle or president of the Church been perfect. Nor am I. Nor are his critics.

“Use every man after his desert,” wrote Shakespeare (in Hamlet II.ii), “and who should ‘scape whipping?” Or, to paraphrase: Treat everybody purely according to his or her merits, and who wouldn’t be worthy of censure or even punishment?

In racial matters, Brigham Young said some things that jar us today, and that we cannot endorse. There’s no denying this. He was, as we all are — even the prophets among us — a man of his time and culture and background.

But he was a good man, a remarkable man, indeed a great man, a sincere disciple of the Lord and a prophet who sought to do God’s will.

I choose to stand with him. “The soul that on Jesus hath leaned for repose I will not, I cannot, desert to his foes.” And, on the specific racial issue described above, President Brigham Young was — notwithstanding the dismissive stereotype of him that’s currently in vogue — on the side of the angels.