The other day, while we were driving about in Virginia, we had some very good views of a full or nearly full moon. And they reminded me of a poetic bit of science writing that I had recently re-encountered, from Dava Sobel, The Planets (New York and London: Penguin Books, 2006). Ms. Sobel begins by talking about the waxing and the waning of the moon

First to come or go is high, round Mare Crisium (the Sea of Crises), followed, as in some fantastic Latin incantation, by Lacus Timoris (the Lake of Fear), Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Calm), Sinus Iridum (the Bay of Rainbows), Oceanus Procellarum (the Ocean of Storms), Palus Somni (the Marsh of Sleep).

Nothing could summon water from those dark seas of the Moon because they are, all of them, dry. Nor have the Moon’s so-called seas ever known the presence of water. Though the lunar maria hinted of a fluid interconnectedness to the first astronomers who eyed them and named them through telescopes, the first Moonwalkers to tread them retrieved the driest imaginable materials from their shores.

“Bone-dry,” the lunar samples were described, though they are much drier than bones, which form inside the Earth’s wet living systems, and retain the memory of water long after death.

Dry as dust, then? No, drier still. On Earth, even dust holds water.

Moon rocks set a new standard of dryness, distinguished by the total absence of water. Not a drop of water, not a bubble of water vapor lurks in the crystal lattice of any Moon rock among the lunar samples, and no ice ever so much as touched them. Comets, however, have probably tucked odd caches of imported water ice – perhaps ten million tons’ worth – in the shadows of unexplored craters near the lunar poles.

Lacking water as a potential ingredient limited the Moon’s creativity to a mere one hundred minerals, while the moist Earth has fabricated several thousand mineral varieties. The gems romantically or religiously associated with the Moon – pearl, quartz, opal, moonstone – could never have formed there, for each requires water in one way or another, and the Moon has none to offer.

The primal lunar scenario currently favored by planetary scientists explains the Moon’s formation and dryness in a single blow: Early in the history of the Solar System, a rogue planet on a collision course struck the infant Earth. The impact, thought to have occurred 4.5 billion years ago, melted impactor and impact site alike, and shot hot debris into space. Swarms of dust and rock fragments, lofted into orbit around the stunned Earth, eventually reunited, 4.4 billion years ago, as the Moon. Having been ejected from one common cauldron, Moon rocks chemically resemble Earth rocks, except that they have lost all their water and any other compounds capable of escape as vapors.

The furious pace of lunar assembly generated enough heat to melt the top layers of the new satellite into a global magma ocean, one hundred miles deep. Over time that ocean gradually cooled and hardened to stone. The errant rubble of the Solar System’s violent youth, still at large then, bombarded the Moon’s smooth new crust, blasting out vast impact basins and craters. Meanwhile radioactive heat trapped inside the young Moon drove more molten rock to the surface, to fill broad basins with black basalt – and paint the Moon’s facial features.

The all-encompassing ocean of magma attending the Moon’s birth was the first fluid to flow there. The rivers and pools of extruded lava were the last, and those froze up three billion years ago. At that time, the rate of cratering tapered off throughout the Solar System, and the Moon, having expended all its internal heat, solidified through and through, turning into a dry fossil generally considered “dead” by geological standards.

The parched Moon pulls at Earth’s seas as though jealous of them. (107-111)

We came in via train this morning from Milan’s Malpensa Airport to Stazione Milano Centrale. It’s a surprisingly long train ride, and our train was even a bit late — which made an already close connection even more exciting than it needed to be. From there, we took a train from Milan to Bologna, and then another train from Bologna to Ravenna.

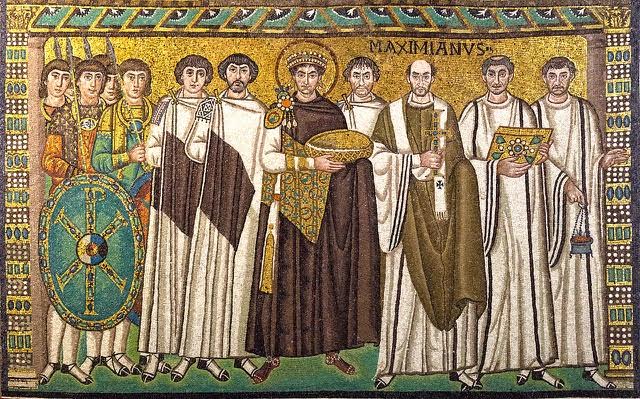

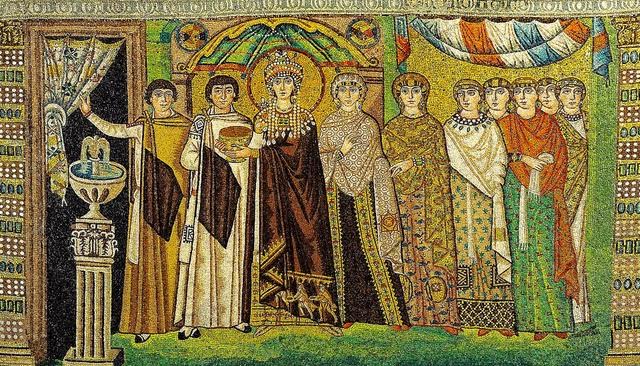

So here we are, staying in a nice little bread-and-breakfast place called Villa Noctis. We’ve wanted to come back for a very long time, and we’ve finally had the opportunity to make it. Ravenna is a very walkable town — at least, for the most part, its historical core is very walkable — and we’ve already managed to take in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (which was built between AD 425 and AD 450) and the Basilica of San Vitale. (which was constructed between AD 526 and AD 547) This is an absolutely marvelous place for Byzantine mosaics, which I love.

Galla Placidia’s mausoleum — it’s actually almost certainly not really hers — provides an obscure reference in the American poet Ezra Pound’s Canto XXI (and, for different reasons, in Cantos XI and XVII), where he writes

Gold fades in the gloom,

Under the blue-black roof, Placidia’s,

He is referring to the gold stars on a dark blue background that appear on the mausoleum’s ceiling, apparently intending to suggest that high cultural moments fade with the passing of time, or perhaps even that brilliant eras and brilliant persons are forgotten in the ignorance that succeeds them and the foolishness that surrounds them. If so, it’s a very Poundian sentiment (for good or for ill). Compare it to these apparently autobiographical opening lines from his poem “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”:

For three years, out of key with his time,He strove to resuscitate the dead artOf poetry; to maintain “the sublime”In the old sense. Wrong from the start—No, hardly, but, seeing he had been bornIn a half savage country, out of date;Bent resolutely on wringing lilies from the acorn.

Pound ended up an ardent and vocal Fascist in Mussolini’s Italy, and possibly insane. During my first trip to Europe many, many years ago as a teenager, I found myself standing in front of a building in Venice where, somebody told me, Ezra Pound lived. (It was probably our expressly pro-Nazi guide — it would fit his interests and predilections — but I can’t say that for sure.) I don’t know if it was true that Ezra Pound lived in that building, but I suspect that it was. He died in Venice in 1972.

Posted from Ravenna, Italy