The intrepid archaeologists over at FAIR Latter-day Saints recently uncovered a 2001 FAIR conference address and posted it to YouTube. It was given by a devilishly handsome fellow who is nearly a quarter of a century younger than I am, and is titled “The Divine Source of the Book of Mormon in the Face of Alternative Theories Advocated by LDS Critics.”

For those who couldn’t open the New York Times link to the actual article that I supplied yesterday, here are some other possibilities for accessing the piece (in whole or, at least, in part) as it was republished elsewhere: Yahoo News Singapore (“For Mormon Missionaries, Some ‘Big, Big Changes’”) and The Buffalo News (“Mormon Missionary Rules 1”), (“Mormon Missionary Rules 2”), (“Mormon Missionary Rules 3”), and (“Mormon Missionary Rules 4”).

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

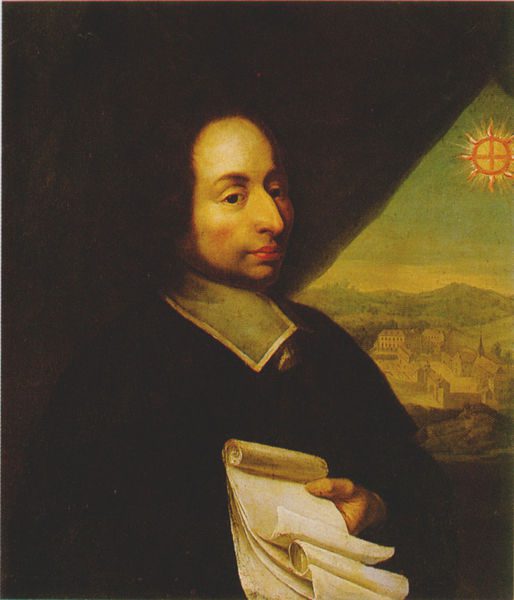

Fundamental to a long-term writing project of mine — or, at least, to its opening chapter — is a famous argument that has come to be called “Pascal’s wager.” As part of my thinking about the wager, I’ve read Michael Rota, Taking Pascal’s Wager: Faith, Evidence and the Abundant Life (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016). At the time that he published Taking Pascal’s Wager, Dr. Rota was an associate professor of philosophy at the University of St. Thomas, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

I try — rather inconsistently, I admit — to use this blog as a mode of storing and sharing notes from my reading, and I’m going to do that in this case. Here are a couple of introductory quotations from Professor Rota on “the seventeenth-century polymath Blaise Pascal” and his famous (and controversial) “wager”:

Pascal made important contributions in mathematics, probability theory and physics. His work on fluid mechanics was instrumental in the later invention of the hydraulic press, and he himself designed and built one of the first mechanical calculating machines, an early precursor to the digital computer. (Interestingly, the principles used in the machine are still employed in many automobile odometers.) Pascal was an inventor, an intellectual and a scientist. He was also a deeply religious man. At the age of thirty-one he had a powerful mystical experience of God. He described the experience in a note and stitched the note into his coat, keeping it close to him. He evidently transferred the paper note (together with a cleaner copy he put down on parchment) from coat to coat for the rest of his life — as a servant found them there after his death. (22-23)

As noted, when Pascal died at the age of just slightly past thirty-nine in 1662, his servant found a small piece of parchment that had been sewn into his coat. At the top of the paper, Pascal had drawn a cross. Underneath the cross were these words:

The Year of Grace 1654

Monday, November 23, day of saint Clement, pope and martyr,

and others in the martyrology.

Vigil of Saint Chrysogonus, martyr, and others.

From about ten-thirty in the evening to about half an hour after

Midnight,

Fire.

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob,

Not of the philosophers and savants.

Certitude, certitude; feeling, joy, peace.

God of Jesus Christ.

Deum meum et Deum vestrum.

“Thy God shall be my God.”

Forgetting the world and everything except God. He is only found by the paths taught in the Gospel.

Grandeur of the human soul.

“Just Father, the world has not known you, but

I have known you.”

Joy, joy, joy, tears of joy.

I separated myself from him: Dereliquerent me fontem aquae vivae [They have forsaken me the fountain of living water]

“My God, will you abandon me?”

May I not be eternally separated from him.

“This is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God,and

Him whom you have sent, Jesus Christ.”

Jesus Christ.

Jesus Christ.

I separated myself from him; I fled him, renounced him,

Crucified him.

May I never be separated from him!

He is only kept by the paths taught in the Gospel.

Total submission to Jesus Christ and to my director.

Eternally in joy for a day of trial on earth.

Non obliviscar sermones tuos [I will not forget your words]. Amen.

[cited by Romano Guardini, Pascal For Our Time (Herder and Herder, 1966), 33-34]

This was Pascal’s reminder to himself of what had evidently been an intense and very personal two-hour religious experience. It occurred when he was approximately thirty-one years old. The historical evidence suggests that he kept the event secret until his death. However, although we know few if any details about, he plainly regarded it as an encounter with God, and as so personally significant that it transformed him and altered the course of his life. He kept his record of it — what scholars today often call “The Memorial” — in the lining of his coat, close to his heart. For the eight years of life that remained to him thereafter, he carefully transferred the document from one coat to another, newly sewing it into the lining every time that he changed his clothing. Obviously, the note preserved Pascal’s memory of a treasured experience, something to which he could return over and over again.

There is, to me, something very moving in Pascal’s story.

Here an interpretive expansion and reformulation of the “wager” given by Professor Rota:

If Christianity is indeed true, then by committing to live a Christian life one brings great joy to God and all others in heaven, raises the chance that one will be with God forever, raises the chance that one will help others attain union with God, expresses gratitude to God, and becomes more aware of God’s love and more receptive to his help in the course of one’s earthly life. On the other hand, if Christianity is false, the person who commits his or her life to Jesus’ teachings has still lived a worthwhile life, striving for moral excellence and experiencing the benefits of religious community (benefits that contemporary sociological research reveals to be significant). (23)