I’m still making an effort to catch up on the reporting of this Interpreter Foundation educational tour:

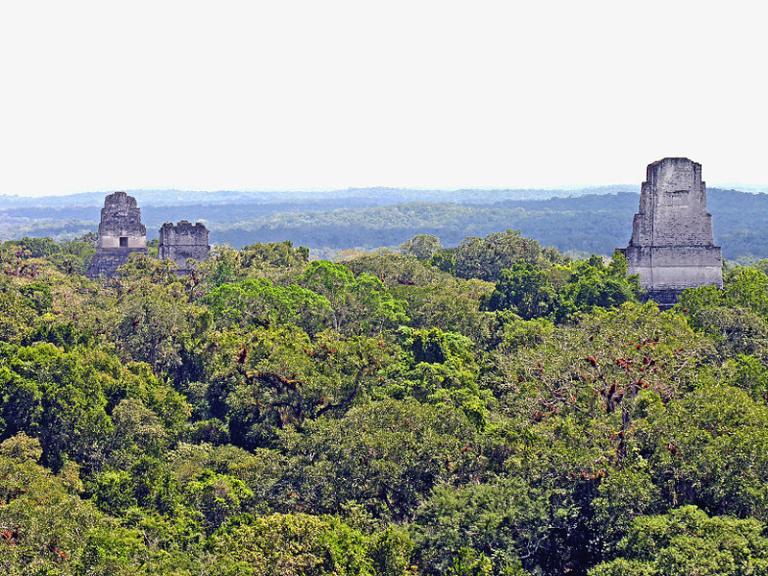

Last Thursday, 24 October, on the morning after the catastrophic computer failure that silenced me for the better part of a week, we spent most of the day walking around a small portion of the Guatemalan Parque nacional Tikal. The ruins of Tikal, which were occupied from approximately 600 BC until about AD 750, are, quite simply, stunning.

The site is surrounded by dense rain forest. Some see this forest as all or part of the Book of Mormon’s “east wilderness” where, under the leadership of the Nephite general (or “captain”) Moroni, a number of fortifications or fortified cities were built during the first century BC:

7 And it came to pass that Moroni caused that his armies should go forth into the east wilderness; yea, and they went forth and drove all the Lamanites who were in the east wilderness into their own lands, which were south of the land of Zarahemla.

8 And the land of Nephi did run in a straight course from the east sea to the west.

9 And it came to pass that when Moroni had driven all the Lamanites out of the east wilderness, which was north of the lands of their own possessions, he caused that the inhabitants who were in the land of Zarahemla and in the land round about should go forth into the east wilderness, even to the borders by the seashore, and possess the land.

10 And he also placed armies on the south, in the borders of their possessions, and caused them to erect fortifications that they might secure their armies and their people from the hands of their enemies.

11 And thus he cut off all the strongholds of the Lamanites in the east wilderness, yea, and also on the west, fortifying the line between the Nephites and the Lamanites, between the land of Zarahemla and the land of Nephi, from the west sea, running by the head of the river Sidon—the Nephites possessing all the land northward, yea, even all the land which was northward of the land Bountiful, according to their pleasure.

12 Thus Moroni, with his armies, which did increase daily because of the assurance of protection which his works did bring forth unto them, did seek to cut off the strength and the power of the Lamanites from off the lands of their possessions, that they should have no power upon the lands of their possession.

13 And it came to pass that the Nephites began the foundation of a city, and they called the name of the city Moroni; and it was by the east sea; and it was on the south by the line of the possessions of the Lamanites.

14 And they also began a foundation for a city between the city of Moroni and the city of Aaron, joining the borders of Aaron and Moroni; and they called the name of the city, or the land, Nephihah.

15 And they also began in that same year to build many cities on the north, one in a particular manner which they called Lehi, which was in the north by the borders of the seashore.

16 And thus ended the twentieth year. (Alma 50:7-16)

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Curiously, Tikal was used as a filming location in Star Wars: Episode IV A New Hope for Yavin 4, the jungle-covered fourth moon orbiting the red gas giant Yavin Prime. Don’t remember it? Before and during the Galactic Civil War, Yavin 4 was the main base and headquarters of the Rebel Alliance. The scene in which Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon is shown landing on Yavin 4 was taken from atop Tikal’s Temple IV looking east toward Temples I, II and III.

A brief aside on Latter-day Saints in film: I said here a few days ago that others would tell our story for us, whether or not we try to tell it ourselves. Six Days in August is still on in theaters, although that may not last much longer. By a large majority, so far as I can tell, people who have seen it have liked it. However, too few have seen it. It will eventually go to DVD and BluRay, and to streaming. Contracts and arrangements are currently being made for that phase.

Six Days in August represented one effort to tell the story of Brigham Young, the Twelve, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But there will soon be another! Executive producer Peter Berg and writer Mark L. Smith have teamed up for American Primeval, which will debut on Netflix come 9 January 2025:

“Helming all six episodes of American Primeval, Berg settled on the Mountain Meadows Massacre as the series’ inciting tragedy. The first episode recreates the murder of hundreds of pioneers traveling from Missouri at the hands of Mormon soldiers, under orders from church president Brigham Young. . . .

“With the Mormon storyline, for instance, Smith’s scripts illustrate how the group got to Utah in the first place, posing the question of why they committed that massacre before setting off a kind of free-for-all in the West.”

Note, by the way, that, judging from the passage above, American Primeval may inflate and exaggerate the death toll in the already horrific Mountain Meadows Massacre. If so, that will certainly help things, won’t it?

MSN: “Mormon pioneers featured in ‘violent’ Netflix drama ‘American Primeval'”:

“Brigham Young is described as ‘a man who will do whatever it takes to secure the survival of his persecuted followers — including using his Mormon army, the Nauvoo Legion.'”

Only four percent of the population of Mexico lives in the state of Chiapas, but more than forty percent of Mexico’s wild animals — the first percentage that I mentioned refers to humans, who are mostly not wild — live in the Tehuantepec, Chiapas, and Lacandone mountains. What comes to mind here is Ether 10:21:

21 And they did preserve the land southward for a wilderness, to get game. And the whole face of the land northward was covered with inhabitants.

We drove out to the beautiful Classic Period ruins of Palenque today, in Chiapas. The ancient city is located not far from the Usumacinta River, which runs roughly parallel to the Rio Grijalva and which has sometimes been identified with the River Sidon was some students of the Book of Mormon — though it has, I think, been losing out to the Grijalva River over the past few academic generations. One of Palenque’s ancient names (in the Itza language) was Lakamha (“big water or big waters,” with the final -ha reminding me, tantalizingly, of the common Book of Mormon noun suffix -hah). It was an important Maya city-state whose ruins have been dated to the period extending between around 226 BC and roughly 799 AD. After its decline (or its puzzlingly sudden abandonment), it was overgrown by the surrounding jungle of cedar, mahogany, and sapodilla trees. In modern times, it has been excavated and restored and is now quite well maintained.

Palenque receives a great deal of rain and is often (as it was today) very, very humid. It is a medium-sized site, smaller than Tikal, Chichen Itza, and Copán, but it contains some of the very finest architecture, sculpture, and roof comb and bas-relief carvings ever created by the Maya. Since the decoding of the Maya hieroglyphs, much of the history of Palenque has been reconstructed on the basis of the inscriptions that appear on many of the monuments; historians now have a long sequence of the ruling dynasty of Palenque in the fifth century and some understanding of its diplomatic, military, and trade relations. The most famous ruler of Palenque was Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal, or Pacal the Great, whose tomb and impressive jade face mask was found and excavated in the Temple of the Inscriptions. By 2005, the site was estimated to be approximately a square mile in extent), but it is estimated that less than 10% of the total area of the city has been explored, which leaves more than a thousand structures still covered by jungle.

Is there anything of any archaeological significance still left to be found in Mesoamerica? You’d better believe it. Consider this amazing article, for example, which was published two days ago by the BBC: “PhD student finds lost city in Mexico jungle by accident”

Posted from Villahermosa, Tabasco, México