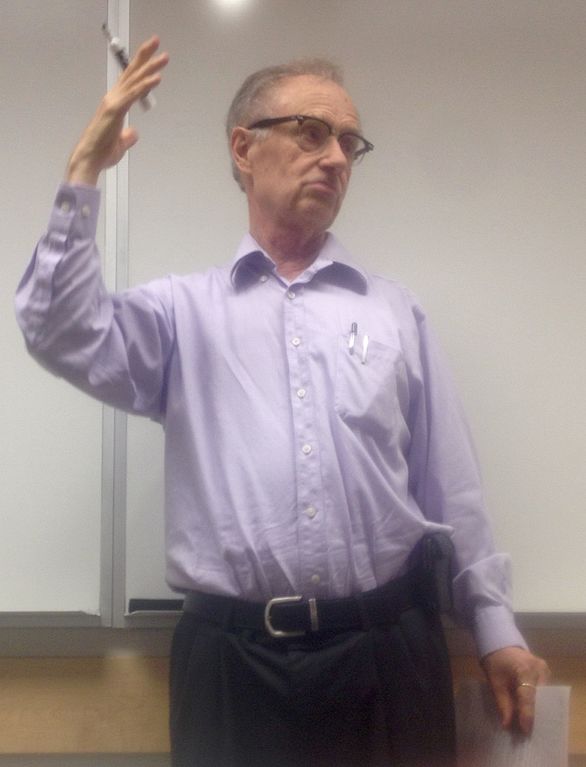

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

My wife and I took Royal Skousen out to dinner last night; we had a pleasant visit before, during, and after the meal. A major topic of conversation, of course, was his wife, Sirkku Unelma Skousen, to whom he was and is deeply devoted. Sirkku died on 9 November 2024, following a lengthy and increasingly difficult illness. (Her funeral will be held on Saturday, 23 November 2024, in Spanish Fork, Utah.) While visiting with him at his home before we went to the restaurant, Royal presented us with an inscribed copy of the latest massive but elegant product of his impressive and enormously important Book of Mormon Critical Text Project: The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Part Seven, The Early Transmissions of the Text. This new book further cements the position of the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project as a major landmark in the history of Latter-day Saint scholarship.

I’ve always been acutely aware of time. Of transience. Evanescence. When I visit famous houses — Hearst’s Castle at San Simeon, King Ludwig’s castles in Bavaria, Vizcaya in Miami, and so forth — I immediately think about how brief the tenure of their owners was and about how long it has been since those owners have been gone. How ephemeral even the wealthy and the powerful are. When I see beautiful flowers, I inescapably, invariably, think of how soon they’ll begin to fade. Years ago, wandering in the Princeton Cemetery — I like cemeteries — I came unexpectedly across the relatively undistinguished burial place of Grover Cleveland, the twenty-second and twenty-fourth president of the United States. He occupied no more ground than did any of the other, less prominent, people who are interred around him.

I made me great works; I builded me houses; I planted me vineyards: I made me gardens and orchards, and I planted trees in them of all kind of fruits: I made me pools of water, to water therewith the wood that bringeth forth trees: I got me servants and maidens, and had servants born in my house; also I had great possessions of great and small cattle above all that were in Jerusalem before me:I gathered me also silver and gold, and the peculiar treasure of kings and of the provinces: I gat me men singers and women singers, and the delights of the sons of men, as musical instruments, and that of all sorts.

So I was great, and increased more than all that were before me in Jerusalem: also my wisdom remained with me.And whatsoever mine eyes desired I kept not from them, I withheld not my heart from any joy; for my heart rejoiced in all my labour: and this was my portion of all my labour.

Then I looked on all the works that my hands had wrought, and on the labour that I had laboured to do: and, behold, all was vanity and vexation of spirit, and there was no profit under the sun.

And I turned myself to behold wisdom, and madness, and folly: for what can the man do that cometh after the king? even that which hath been already done.Then I saw that wisdom excelleth folly, as far as light excelleth darkness.The wise man’s eyes are in his head; but the fool walketh in darkness: and I myself perceived also that one event happeneth to them all.

Then said I in my heart, As it happeneth to the fool, so it happeneth even to me; and why was I then more wise? Then I said in my heart, that this also is vanity. For there is no remembrance of the wise more than of the fool for ever; seeing that which now is in the days to come shall all be forgotten. And how dieth the wise man? as the fool.

Therefore I hated life; because the work that is wrought under the sun is grievous unto me: for all is vanity and vexation of spirit. Yea, I hated all my labour which I had taken under the sun: because I should leave it unto the man that shall be after me.And who knoweth whether he shall be a wise man or a fool? yet shall he have rule over all my labour wherein I have laboured, and wherein I have shewed myself wise under the sun. This is also vanity.

Therefore I went about to cause my heart to despair of all the labour which I took under the sun.For there is a man whose labour is in wisdom, and in knowledge, and in equity; yet to a man that hath not laboured therein shall he leave it for his portion. This also is vanity and a great evil.For what hath man of all his labour, and of the vexation of his heart, wherein he hath laboured under the sun? (Ecclesiastes 1:4-22)

“We are but a moment’s sunlight, fading in the grass,” run the lyrics of a 1967 song that I used to sing, strumming along on my twelve-string. And I really felt it, even then.

Perhaps my overdeveloped sense of the passing, ephemeral character of all earthly things is the reason behind my lifelong fondness for the poetry of A. E. Housman. Consider, for example, his poem “To an Athlete Dying Young”:

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.To-day, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay,

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears:Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl’s.

As I shuffle inexorably toward the grave, I find myself thinking back to people to whom I was once very close but with whom I’ve long since lost contact for simple reasons of geographical and chronological distance. Some of these are childhood friends. More are people whom I knew in high school or even as an undergraduate. I expect that at least a small number of them have already passed on. At the time we were close, it seemed simply inconceivable that we would ever drift apart. But we did. Accordingly, they are enshrined in my memory as they appeared in life many decades ago. Very occasionally, though, I’ll come across a current photograph of them as they look today, and I’m inevitably shocked to discover that, like me, they’ve aged.

So I’ve loved Ēriks Ešenvalds’s setting of “Only in Sleep” since I first heard it. The lyrics are from a poem by the American poet Sara Teasdale (1884-1933). And here is that setting, beautifully performed by the Choir of Trinity College Cambridge, directed by Stephen Layton, in Trinity College Chapel. The angelic solo voice belongs to Rachel Ambrose Evans:

Only in sleep I see their faces,

Children I played with when I was a child,

Louise comes back with her brown hair braided,

Annie with ringlets warm and wild.Only in sleep Time is forgotten —

What may have come to them, who can know?

Yet we played last night as long ago,

And the doll-house stood at the turn of the stair.The years had not sharpened their smooth round faces,

I met their eyes and found them mild —

Do they, too, dream of me, I wonder,

And for them am I too a child?

Tragically, Sara Teasdale, who had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1918 for her 1917 poetry collection, Love Songs, committed suicide near the very beginning of 1933 at the age of forty-eight. Her marriage had ended in divorce just a few years before, and the poet Vachel Lindsay, who had been the love of her life even before her wedding, had committed suicide himself at the end of 1931. In her 1915 collection Rivers to the Sea, which appeared a full eighteen years before her death, she had published a brief poem entitled “I Shall Not Care”:

When I am dead and over me bright April

Shakes out her rain-drenched hair,

Though you shall lean above me broken-hearted,

I shall not care.I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful

When rain bends down the bough;

And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted

Than you are now.

I mourn the despair of Sara Teasdale and Vachel Lindsay and innumerable others. I regard human personalities as the most interesting and valuable things in the known universe, and their departure under any circumstance seems to me inexpressibly sad, an inconsolable loss. And yet, like animals grazing in a meadow who are startled by the crack of a rifle and who look up briefly when one of their companions falls to the ground, dead, but who then resume grazing as before, we take death for granted. We put it out of our minds until we are forced to face it.

I remember driving to the cemetery for the burial of my father. I’ve never forgotten my astonished recognition that life simply went on — with people running their errands, lined up for fast food restaurants, singing along with thumping car radios — in the face of the most non-trivial of all things, the supreme offense against life: the cosmic obscenity of death.

Just before and just after my father’s passing, the yearning words of a hymn kept running through my mind — a hymn that, prior to that time, had never been especially important to me:

- Abide with me; fast falls the eventide;

The darkness deepens; Lord, with me abide;

When other helpers fail and comforts flee,

Help of the helpless, oh, abide with me. - Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see—

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

While my mother was taking her final breaths, that same hymn was playing over the speakers in the critical-care unit.

Change and decay in all around I see—

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

That is my own prayer, as well. Only the hope of immortality and eternal life offers any comfort in the presence of ultimate mortal loss.