This new item has now gone up on the website of the Interpreter Foundation: The Temple: Plates, Patterns, & Patriarchs: “From Jared to Jacob: The Motif of Divine Ascensus and Descensus in Genesis, the Book of Moses, and the Enochic Tradition,” written by Matthew L. Bowen and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

We left Cardiff this morning to drive to Oxford. En route, Peter Fagg shared some passages from Dylan Thomas’s 1954 BBC radio play Under Milk Wood, an interesting portrayal of life in a fictional Welsh town. He is an exceptionally good voice actor, adept at dialects and distinct personalities. A few days ago, at Dove Cottage in Grasmere, he recited Roald Dahl’s satirical retelling of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” from memory. It’s really funny, but especially in his recital of it. I’ve heard him do it before; I would love to get him to record the piece. As he pointed out to us, Roald Dahl, was born to Norwegian immigrant parents (as his name might suggest) in Cardiff.

Then Kris Frederickson and I took turns on the microphone, talking about Oxford and, as it turned out, focusing heavily on C. S. Lewis, who is, of course, strongly associated with the University of Oxford, where he studied, taught, and is buried. I’ll share a few of the passages from him that we shared on the motor coach. The first was mine, a favorite of long standing:

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which,if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree helping each other to one or the other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all of our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations – these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit – immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.” (The Weight of Glory)

Kris shared a number of her own favorites, including this one:

“To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.” (The Four Loves)

And this one, which reminds me of the passage from Wordworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” that I cited here a few days ago:

“If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that we were made for another world.” (Mere Christianity)

And this one:

“We are, not metaphorically but in very truth, a Divine work of art, something that God is making, and therefore something with which he will not be satisfied until it has a certain character. Here again we come up against what I have called the ‘intolerable compliment.’ Over a sketch made idly to amuse a child, an artist may not take much trouble: he may be content to let it go even thought it is not exactly as he meant it to be. But over the great picture of his life—the work which he loves, though in a different fashion, as intensely as a man loves a woman or a mother a child—he will take endless trouble—and would, doubtless, thereby give endless trouble to the picture if it were sentient. One can imagine a sentient picture, after being rubbed and scraped and recommenced for the tenth time, wishing that it were only a thumbnail sketch whose asking was over in a minute. In the same way, it is natural for us to wish that God had designed for us a less glorious and less arduous destiny; but then we are wishing not for more love, but less.” (The Problem of Pain)

Which reminded me of a passage that I didn’t share, but certainly could have:

“Imagine yourself as a living house. God comes in to rebuild that house. At first, perhaps, you can understand what He is doing. He is getting the drains right and stopping the leaks in the roof and so on; you knew that those jobs needed doing and so you are not surprised. But presently He starts knocking the house about in a way that hurts abominably and does not seem to make any sense. What on earth is He up to? The explanation is that He is building quite a different house from the one you thought of – throwing out a new wing here, putting on an extra floor there, running up towers, making courtyards. You thought you were being made into a decent little cottage: but He is building a palace. He intends to come and live in it Himself.” (Mere Christianity)

I did, however, share this one with the unfortunate passengers of the coach, who had nowhere to run:

“I am trying to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: ‘I am ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I do not accept His claim to be God.’ That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic–on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg–or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon, or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God. But let us not come up with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. We are faced, then, with a frightening alternative. This man we are talking about either was (and is) just what He said, or else a lunatic, or something worse. I have to accept the view that He was and is God.” (Mere Christianity)

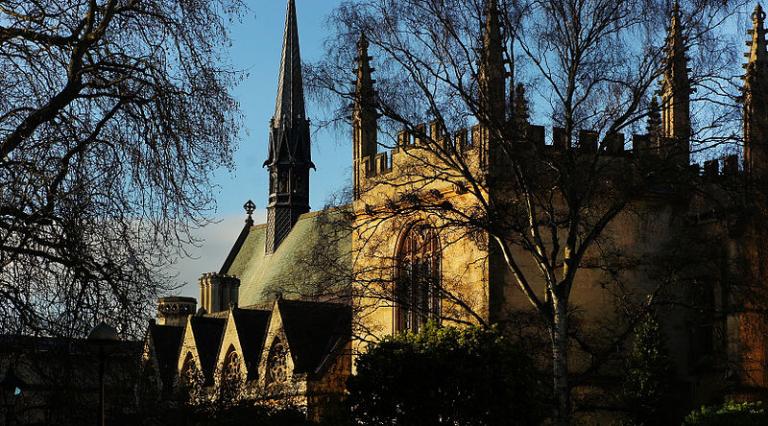

We did a walking tour in Oxford, walking past several of the colleges; the Sheldonian Theatre and the Radcliffe Camera; the monument commemorating the “Oxford Martyrs” (Bishop Nicholas Ridley, Bishop Hugh Latimer, and Thomas Cranmer, the deposed Archbishop of Canterbury) who were burned at the stake under Queen Mary I (aka “Bloody Mary”); through the courtyard of the Balliol Library; and so forth. Afterwards, we had some time on our own. My wife and I spent ours in the Covered Market and in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin, where John Wesley preached and where John Henry Newman served as the vicar (before he converted to Catholicism and rose to the rank of cardinal). Among other things, too, the trials of the Oxford Martyrs were held in the church and, in early 1942, C. S. Lewis preached the lay sermon in it that was later published as The Weight of Glory. It’s the essay from which I took my first quotation, above.

Posted from London, England