(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

We did more interviewing today up at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City. The interviews are for the Interpreter Foundation’s forthcoming series of short Becoming Brigham documentary videos. I was intending to be there, even though I wasn’t slated to do the actual interviewing today. In the end, though, I thought that I had better stay home and work on several projects that have fallen a bit behind with all of my recent travel. Today’s interviews were conducted by Camrey Bagley Fox, who played Emma Smith in Witnesses (2021) and in Six Days in August (2024).

Tomorrow (Thursday, 31 July 2025) is the last day to purchase tickets to this year’s rapidly approaching FAIR Conference in advance, and to use any discount codes! In-person tickets will not be available at the door this year, so be sure to buy your tickets no later than tomorrow (Thursday). If you’re at all interested in attending in person, you need to know that the window for buying tickets is rapidly closing.

I’ll now share a few more passages that I marked during a recent re-reading of Extraordinary Knowing: Science, Skepticism, and the Inexplicable Powers of the Human Mind, written by the late Elizabeth Lloyd Mayer, a professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley:

I began discovering mountains of research and a vast relevant literature I hadn’t known existed. As astonished as I was by the sheer quantity, I was equally astonished by the high caliber. Much of the research not only met but far exceeded ordinary standards of rigorous mainstream science. . . .Every good scientist knows the famous dictum first enunciated by sociologist Marcello Truzzi and later popularized by astronomer and author Carl Sagan: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” The claims made by the research I was reading were plenty extraordinary. They suggest the existence of mental capacities that defy space, time, and the basic boundaries of individual identity. Anything less than superb evidence won’t begin to justify claims like that. As a result, a good deal of research on anomalous mental capacities—certainly not all, but enough to be startling—adheres to stunningly high standards. Outside assessments of that research have repeatedly determined, often to the significant surprise of the evaluators, that the studies are overall scrupulously controlled, rigorously designed, and carefully regulated by masked and double-blind procedures. (69-70)

[W] ere I asked to point to a scientific journal where hard-headedness and never-sleeping suspicion of sources of error might be seen in their full bloom, I think I should have to fall back on the Proceedings of the “Society for Psychical Research.” . . . Quality, and not mere quantity, is what has been mainly kept in mind. The most that could be done with every reported case has been done. The witnesses, where possible, have been cross-examined personally, the collateral facts have been looked up, and the narrative appears with its precise coefficient of evidential work stamped on it, so that all may know just what its weight as proof may be. (77)

He himself was convinced that anomalous mental capacities were real and hugely significant. He was particularly fascinated by telepathy, which he’d dubbed thought transference. He enthusiastically pursued its investigation with a few close associates, in particular a Hungarian psychoanalyst named Sándor Ferenczi, with whom he’d begun a collegial correspondence in 1908. On August 20, 1910, Freud triumphantly wrote to Ferenczi, “Your—carefully preserved—observations… seem to me finally to shatter the doubts about the existence of thought transference. Now it is a matter of getting used to it in your thoughts and losing respect for its novelty and also preserving the secret long enough in the maternal womb, but that is where the doubt ends.” (80)

On October 6, 1909, he wrote, “. . . Keep quiet about it for the time being, we will have to engage in future experiments. . . .” A few days later, concerned that he hadn’t been emphatic enough, he added, “. . . [ L]et us keep absolute silence with regard to it. The only one whom I have drawn into the secret is Heller, who also has had experiences with it. We want to initiate Jung at a later date. . . . Think out some good plans and have your brother formulate experiments. . . . I am almost afraid that you have begun to recognize something big here, but we will encounter the greatest difficulties in exploiting it.” (81)

At the end of his long and extraordinary career, Freud made a remarkable statement. If, he said, he had it to do over again, he might devote his life to the study of thought transference. In an unpublished letter to Hereward Carrington, a leading investigator with the Society for Psychical Research, Freud wrote, “I am not one of those who from the outset disapprove of the study of the so-called occult psychological phenomena as unscientific, as unworthy or even as dangerous. If I were at the beginning of a scientific career, instead of as now at its end, I would perhaps choose no other field of work in spite of all difficulties.” (82)

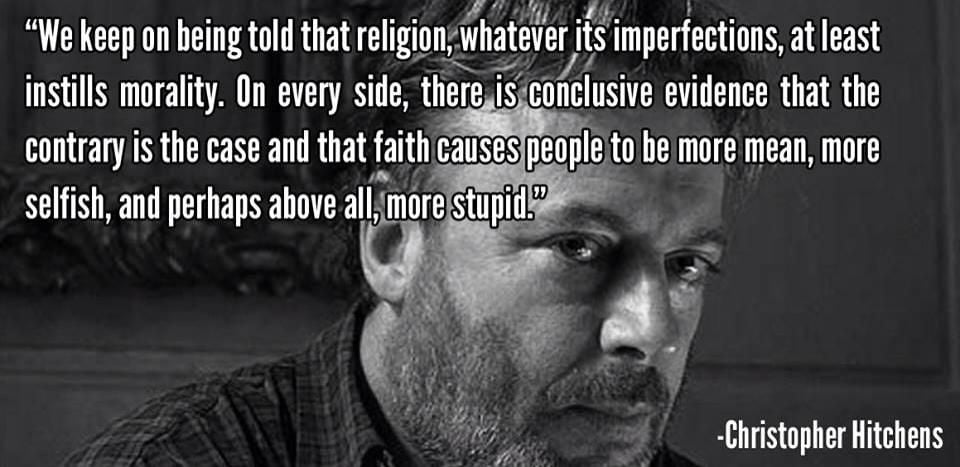

I close, as I often do, with a few items from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™: Decent secular people can almost tolerate the evils of theism. Surely, though, when theists exploit children in their relentlessly mean-spirited, selfish, and stupid crusade against humanity, that crosses a line that should never be crossed. Yet religious believers do it nonetheless, and they do it without shame:

- “Little Hands, Big Impact: Calgary Primary Children Serve Local Youth in Need”

- “Youth in Oregon Stake Host Inclusive Games for Community Members with Disabilities: Latter-day Saint youth in Oregon foster camaraderie and new friendships by organizing inclusive games activity”

And, if those abominations aren’t already enough to sink you into the pit of irretrievable despair, consider these further horrors:

- “Charlottetown Food Bank Gets a Lift.”

- “Missionaries in Action: Service That Transforms Communities”