Bukhara and Samarkand, where I’ve spent pretty much the past week, lie in what the West has long called Transoxiana (roughly, “beyond the [River] Oxus”). The name was first coined by Alexander the Great [“the Great”!) — or, anyway, by somebody in his entourage, in the fourth century BC. I’ve always been amused by the corresponding Arabic term for the area, which is Mā Warāʾ an-Nahr (ما وراء النهر, “what is beyond the river”).

The corresponding Chinese term for the region — because, yes, this is an area that has historically been influenced by, and has influenced, both Greece and China, and where Asiatic facial features are quite common — is Hezhong (“land between rivers”; something like “Mesopotamia,” which the West typically uses for Iraq, between the Tigris and the Euphrates). It is the area between the Oxus River (the Amu Darya, roughly to the southwest) and the Jaxartes River (the Syr Darya), roughly to the northeast.)

Medieval Arabic and Islamic sources call the Oxus River or Amu Darya the Jeyhoun (جَـيْـحُـوْن, Jayḥūn), which is cognate with Gihon, the biblical name for one of the four rivers of the Garden of Eden. (See Genesis 2:10-14.).

The Amu Darya or Oxus River forms the border between Iran and Turan, which is important to understand. In Persian lore, the distinction between Iran and Turan — the land of light and the land of darkness, rather comparable to the distinction between Israel and the goyim (or “gentiles”) or between the Greeks and the barbaroi, the “barbarians” (whose meaningless gibberish sounded, to the Greeks, like bar-bar-bar-bar) — is fundamental. (I would even suggest that it plays a role in at least some contemporary Iranian political thinking and discourse.)

Turan is a rather slippery term, though. It could and can seem to refer broadly to non-Iranian areas and peoples. After the arrival of the Turks to the area, it was sometimes applied to them. And the title character of Puccini’s magnificent opera Turandot [= Persian Turandokhtar, “daughter of Turan”] is, of course, a royal Chinese princess.

Anyway, though, this area is the historical Turan. And, all over the place, I’ve seen references to Afrasiyab, which is the name of both a place within Samarkand and a powerful Turanian ruler who figures prominently in the Persian national epic, the Shahnameh, whom I’ve always regarded as something of a villain. Not so much here, though!

And part of it is also the ancient Sogdia, where the Sogdians, who were originally Zoroastrians, wrote important documents in an old form of Persian that also bears the name Sogdian.

The region was conquered by Qutayba b. Muslim between 706 and 715 and, thereafter, gradually became Muslim. But it may have been Buddhist before it was Zoroastrian; the Tang Dynasty Chinese sometimes controlled the eastern part of what is today Uzbekistan. Importantly, paper-making may have arisen in the area under Chinese influence and, from here, been transmitted first to the Islamic world and then to the West.

The name of Samarkand probably derives from the Persian/Sogdian samar (“stone,” “rock”) and kand (“fort,” “town”). If that’s true, it’s linguistically equivalent to the name of Uzbekistan’s capital city to the east of Samarqand, which is Tashkent (Turkic tash [“stone”] and kent (borrowed from Persian/Sogdian kand).

Samarkand is one of oldest cities in central Asia. It was probably already several centuries old when it was conquered by Alexander the Great [sic] in 329 BC, and its population was a multi-religious and multiethnic one back even for diversity was fashionable. At the time that Qutayba b. Muslim captured the city from the Tang Dynasty around AD 710, the majority of its residents were adherents of Zoroastrianism, but Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism, and Nestorian Christianity were also represented.

Samarkand was governed by Iranian and Turkic rulers until Ghengis Khan and the Mongols conquered it in 1220 AD. The great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta — far more widely traveled that Marco Polo — visited Samarkand in 1333 and pronounced it “one of the greatest and finest of cities, and the most perfect of them in beauty.”

But the best (in a sense) was yet to come: The amir Timur-i Leng — the problematically titled “Timur the Great” — made it his capital, and it became the birthplace of the so-called Timurid Renaissance.

I’ve already mentioned Timur here, in a blog entry from just a few days ago, and it has drawn criticism. But I’ll say just a little bit more about him. He was a Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire, which essentially covered modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia. An undefeated commander, he is widely regarded as one of the greatest of all military leaders and tacticians. Additionally, he was a a great patron of art and architecture, and that is shown most clearly in Samarkand. Great names such as that of the brilliant historical and social theorist Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) and the great Persian lyric poet Hafez (1325-1390) have been associated with Timur.

I’ll take Hafez first and, since I’m running out of time and energy, I’ll simply cite the retelling of the relevant story in Wikipedia:

In one tale, Timur angrily summoned Hafez to account for one of his verses:

‘agar ‘ān Tork-e Šīrāzī * be dast ārad del-ē mā-rā

be khāl-ē Hendu-yaš baxšam * Samarqand ō Boxārā-rāIf that Shirazi Turk accepts my heart in their hand,

for their Indian mole I will give Samarkand and Bukhara.

Samarkand was Timur’s capital and Bukhara was the kingdom’s finest city. “With the blows of my lustrous sword”, Timur complained, “I have subjugated most of the habitable globe… to embellish Samarkand and Bokhara, the seats of my government; and you would sell them for the black mole of some girl in Shiraz!”

Hafez, the tale goes, bowed deeply and replied, “Alas, O Prince, it is this prodigality which is the cause of the misery in which you find me”. So surprised and pleased was Timur with this response that he dismissed Hafez with handsome gifts.

Such an encounter, if it really happened, might have been terrifying, because Timur was a brutal and deadly man who was responsible for the deaths of millions of people.

For Ibn Khaldun’s rather nerve-wracking audience with Timur, see “The Scholar and the Sultan: A Translation of the Historic Encounter between Ibn Khaldun and Timur.”

Notwithstanding his (in my judgment) pathological cruelty, Timur did some good things. For one, he introduced a form of urban planning and, over the course of thirty-five years, built and rebuilt most of the city of Samarkand; he was directly involved in his construction projects. When he didn’t flatly kill them, he brought great artisans and craftsmen from all over his empire to beautify his capital, which became the site of his mausoleum, the Gur-i Mir (or Gur-e Amir).

Ulugh Beg, Timur’s grandson (who ruled from 1409 until his death in 1449, is also worthy of note. His passion was astronomy (and, to some degree, mathematics) and, much in the style of his grandfather, he brought astronomers from all over the empire and beyond to his capital of Samarkand, where in 1428, he built a very famous (though sadly short-lived) observatory.

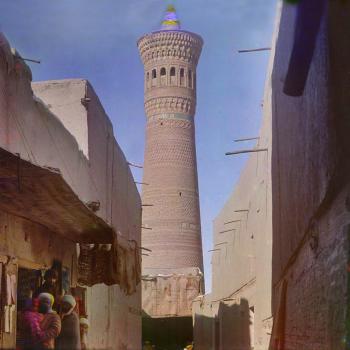

Like Samarkand, Bukhara is located on the ancient Silk Road and was a center of trade, scholarship, culture, and religion. The complex religious history of the region appears in the origin of its name: According to some, the name Bukhara dates back to the Sanskrit vihara (a term for a Buddhist monastery). According to others, the name Bukhara is possibly derived from the Sogdian βuxārak (‘Place of Good Fortune’), a name for, again, a Buddhist monastery.

By 850, after the Muslim Arab conquest, Bukhara served as the capital of the Samanid Empire. This important because, as the power of the caliphate in Baghdad waned, local cultures began to reassert themselves on the margins of the Abbasid empire. The Samanids, in particular, rejuvenated Persian culture far from Baghdad, the erstwhile center of the Islamic world. Older forms of the Persian language had effectively gone underground for a while, but then they reappeared in a form that was heavily influenced by Arabic (and written in a modified Arabic script). This was “New Persian.”

Rudaki (858-940), the father of New Persian poetry, was born and raised in Bukhara. (Perhaps his most famous poem is about the beauty of Bukhara itself.) So, for that matter, was Imam al-Bukhari (810-870), generally considered the most important scholar of hadith in the history of Sunni Islam. Ibn Sina (aka Avicenna [ca. 980-1037]) was also raised in Bukhara. He is often described as the father of early modern medicine –his most famous medical works being The Book of Healing, a philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia that was standard at many medieval and early modern European universities as late as 1650 — and is generally ranked the greatest of all Muslim philosophers. (He even receives favorable mention in Dante’s Inferno, and some of his work was published by Brigham Young University’s one-time Islamic Translation Series.) Besides philosophy and medicine, Avicenna’s vast body of work includes writings on astronomy, alchemy, geography, geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, and physics, and even some poetry.

Some of us traveled by train from Samarkand to Tashkent on Thursday night (local time), and the long, long, long return home begins shortly with a flight from Tashkent, the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan.

Like other cities in the area, Tashkent is overwhelmingly Muslim now, but it was once an active location for Buddhist monasteries. Genghis Khan destroyed it in 1219, and it lost much of its population. And Timur swept through in the 1300s in his characteristically gentle manner.

In 1966, a shallow earthquake measuring 5.2 on the Richter scale had its epicenter right beneath the center of the city. The quake killed perhaps two hundred people, and left 200,000 or 300,000 homeless. Less damage, perhaps, than Timur did.

Posted from Tashkent, Uzbekistan