(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

A short article by Matthew Hutson in the October 2019 issue of Scientific American (“Beautiful Truths: Nonmathematicians agree on what makes proofs pleasing,” on pages 14-15) revisits the interesting issue of the relationship between mathematical truth and what is often called not just “beauty” but “elegance”:

“Scientists and mathematicians,” Hutson writes, “often describe facts, theories and proofs as ‘beautiful,’ even using aesthetics to guide their work. Their criteria might seem opaque to nonexperts, but new research finds that novices can consistently assess a proof’s beauty or ugliness.”

Stefan Steinerberger, a mathematician at Yale University, and Samuel Johnson, a psychologist at England’s University of Bath, conducted three experiments for a study on the subject that was apparently published in the August issue of Cognition. For each experiment, they analyzed approximate 200 responses.

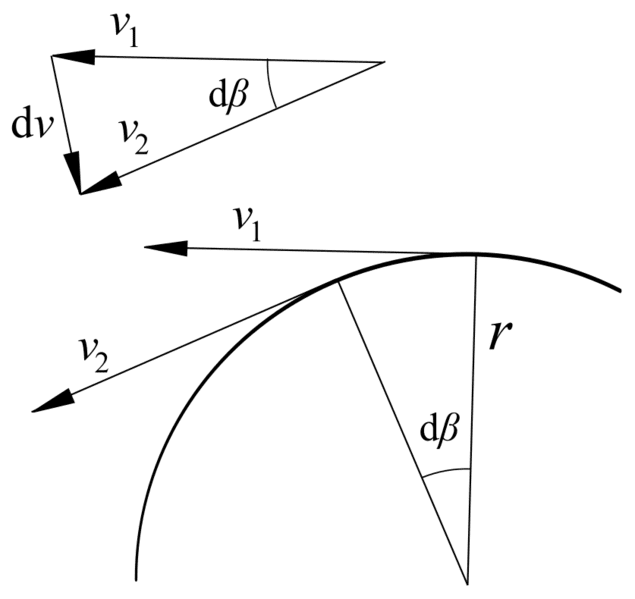

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

The respondents had attended college but were not mathematicians. In each of the experiments, they read through four simple mathematical arguments that were within their range and were tested for their comprehension. Then, the respondents were asked to rate the “similarity” of each argument to each of four landscape paintings.

The results were distinctly consistent. That is to say that the respondents generally agreed on which arguments matched which paintings — and, more significantly, their choices generally agreed with those made by eight professional mathematicians.

For one of the three experiments, participants in the study were asked to rate both the paintings and the arguments by means of ten adjectives, which included beautiful. Once again, results were consistent. “Elegance” was the foremost criterion for judging beauty in both mathematical arguments and landscape paintings. “Profundity” and “clarity” were the next most significant qualities in the judgments of the study’s respondents.

More than a few mathematicians and physicists have claimed to use “beauty” and “elegance” as indicators of truth, even before evidence has turned up. Others have challenged this. If there is any truth in it, though, it seems to suggest something very significant about the nature of the cosmos: Why, for example, should the mathematical equations that describe the universe be orderly? Why should they be “beautiful” and “elegant”?

And please recall that the Greek word cosmos actually suggests “beauty” and orderliness. The Greeks opposed cosmos to chaos, and the term is related to words like cosmetics and cosmetology.

“‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ – that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” So wrote the English poet John Keats in his “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” which was first published in 1819.

Maybe he went too far. Maybe he didn’t.