(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo

But, first, a new item on the website of the Interpreter Foundation:

Science & Mormonism Series 1: Cosmos, Earth, and Man Questions and Comments about Evolution

Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article by David M. Belnap originally appeared in Science & Mormonism Series 1: Cosmos, Earth, and Man (2016).

Abstract: David Belnap, professor of biochemistry and biology at the University of Utah, answers questions about evolution that commonly come up in discussions among Latter-day Saints.

***

And now on to our main feature, a column that I published in the Provo Daily Herald back around 11 November 1999:

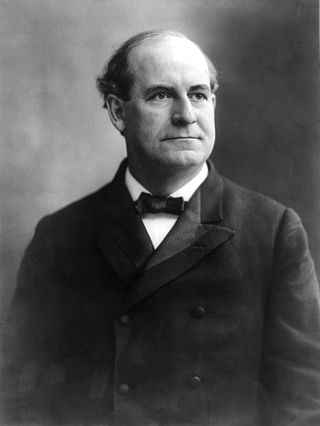

In summer 1925, in a village called Dayton, John Scopes was charged with violating Tennessee’s ban on teaching organic evolution in public schools. The great orator, onetime presidential candidate, and former secretary of state William Jennings Bryan joined the prosecution; the famous criminal defense lawyer Clarence Darrow came to the aid of Scopes. Late in the trial, Darrow called Bryan to the witness stand and, by most accounts, Bryan performed disastrously. Scopes was convicted. Bryan died a few days later. The trial entered American legend.

But the legend is historically inaccurate. So, at least, argues Edward Larson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion.

Larson says the myth first emerged in 1931 with Frederick Lewis Allen’s best-selling Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties. It culminated in 1960, with the film release of Inherit the Wind, starring Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, and Gene Kelly.

Allen’s book sold more copies — over a million — than any other nonfiction of the thirties, served as a college textbook for over fifty years, and profoundly affected serious historians. Although his account of the trial manifests numerous factual errors, those were the least of its problems. He depicted the case, declares Larson, with “cartoonlike simplicity.” The Scopes trial was pressed into service, and distorted, to support Allen’s theory that America jettisoned Victorianism during the twenties. Since, for Allen, fundamentalism meant anti-evolutionism and anti-evolutionism meant William Jennings Bryan, Bryan’s personal humiliation at Dayton became a decisive defeat for fundamentalism in general. But no evidence supports such a notion. Quite reasonably, the anti-evolutionists had seen Scopes’s conviction as a victory. Their activity actually increased over the next few years; additional states banned the teaching of evolution. National textbook publishers, fearing legal challenges, weakened their language on the subject. Even Allen himself acknowledged that statistics revealed no decline in American piety. Indeed, fundamentalist churches continued to grow. Nonetheless, imposing his own biography upon the rest of the nation, he insisted that the statistics masked weakened loyalties to church and faith.

All subsequent commentators who insisted that fundamentalism was dead were Northerners; of the South they took no notice. But fundamentalism, which had begun in revivals in the urban North and along the West Coast, was flourishing in the South, constructing a separate subculture with its own religious, educational, and social institutions, including colleges. “Although the Scopes trial helped push fundamentalists out of mainstream American culture,” writes Larson, “they seemed almost eager to go.” They were preparing for the evangelical resurgence that we have witnessed in our own time.

With the rise of McCarthyism in the 1950s, interest in the Scopes trial rekindled. Fundamentalist Protestants tend to political conservatism — though, ironically, Bryan was quite liberal — so the stereotype of them as ignorant enemies of progress was perfect for propaganda use. Jerome Lawrence and Robert Lee’s play Inherit the Wind used a thinly disguised Scopes trial much as Arthur Miller’s The Crucible used the Salem witch trials — to attack Senator McCarthy. Foreshadowing modern “docudrama,” they fictionalized dialogue, invented and deleted characters, added love interests, and propagandized recklessly. The play’s fire-breathing fundamentalist pastor, who oppresses his townspeople until the Darrow-figure liberates them, is pure imagination. Instead, leading Dayton citizens hatched the idea of a trial while sitting in Robinson’s Drugstore, hoping to attract media attention and tourist dollars. Scopes’s accusers, his evolutionist friends, provided his defense.

The play makes Bryan a whining fool, caricatures his testimony, and suppresses his concerns about the ethical and political implications of Darwinian “survival of the fittest.” By contrast, Clarence Darrow, a militant and rather obnoxious atheist, becomes a sensitive soul who respects the faith he is unable to share. The play’s teacher is dragged from his classroom and threatened with jail. In reality, he was assessed a $100 fine – which Bryan opposed and offered to pay. Scopes actually won several college scholarships.

According to Inherit the Wind, the persecution of John Scopes destroyed fundamentalist anti-evolutionism forever. That is false, and there was no persecution. Yet the play continues to be assigned in American history classrooms as a reliable window into the 1920s and into the relationship of science and religion.