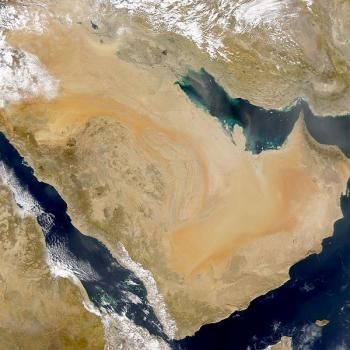

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo by “olekinderhook”)

A couple of stories will make clear the power that poets were thought to enjoy [among the ancient, pre-Islamic Arabs].

The first concerns a man by the name of Maymun ibn Qays, who is generally known by the name of al-Asha. He was a professional troubadour, to borrow a later term. He traveled from one end of the Arabian Peninsula to the other, harp in hand, singing the praises of those wise enough to reward him. He was also famous as a satirist, though, and a person to whom he offered his services would have to be very brave indeed to refuse him the reward he sought. For if al-Asha thought himself slighted, the person at whose hands the offense came was likely to wake up one morning as the butt of a stinging song or versified joke that would soon be on everyone’s lips across all Arabia. Al-Asha survived into the days of the Prophet Muhammad, and it’s during this time, late in his life, that the story occurs that I’ll now tell:

Al-Asha set out to visit Muhammad.[1] He had composed an ode in honor of the Prophet and wanted to recite it in the Prophet’s presence. When Muhammad’s enemies, the Quraysh, heard about this, they were terrified that their enemy’s prestige would be significantly enhanced by his being praised by so famous and popular a poet. So they intercepted al-Asha on his journey and politely asked him where he was headed.

“To your relative Muhammad,” he said. “I intend to accept Islam.”

“Oh no,” they replied. “You don’t really want to do that! Don’t you realize that Muhammad will forbid you to do certain things that you like to do?”

“Like what?” al-Asha inquired.

“Like fornication,” they said.

“Oh,” he replied. “That’s no big deal. I haven’t abandoned it, but it has certainly abandoned me! What else?”

“Gambling. Muhammad won’t allow you to gamble.”

“That’s fine. Maybe he’ll give me something that will compensate me for the loss of gambling. What else?”

“Usury. He won’t permit you to lend money out at interest.”

“I’ve never borrowed or lent anyway. What else?”

“Wine.”

“I’ll drink water.”

Seeing that al-Asha couldn’t be talked out of going to Muhammad and accepting Islam, the representatives of Quraysh changed their approach. They offered him a hundred camels if he would simply go home and wait for a while, to see what the outcome would be of the struggle they were waging against Muhammad. If they won, which they had every intention of doing, there would soon enough be no Islam for him to accept and no danger if he did. And if they lost . . . well, they had no intention of losing.

“I agree,” said al-Asha.

“O Quraysh,” cried the leader of the men, “this is al-Asha, and I promise you that if he becomes a follower of Muhammad he will inflame the Arabs against you by his poetry. Therefore, hurry and collect a hundred camels for him. It is a small enough price to pay!”

Camels, as we’ve already seen, were among the pre-Islamic Arabs’ most valued possessions. They carried him, along with his family and his property. They gave him milk and, sometimes, meat. They were an emblem of his pride. Yet, threatened by the damage that a poet’s words might do them, the Quraysh hastened to buy that poet off with a large herd of camels.

[1] A word about the name Muhammad: Over the years, it has been variously spelled by English writers. Mahomet, Mohammed, Muhammed, and even the disrespectful Mahound are all forms of the same proper name. Muhammad, however, represents the Arabic most faithfully and is becoming the standard transliteration.

Posted from Steamboat Springs, Colorado