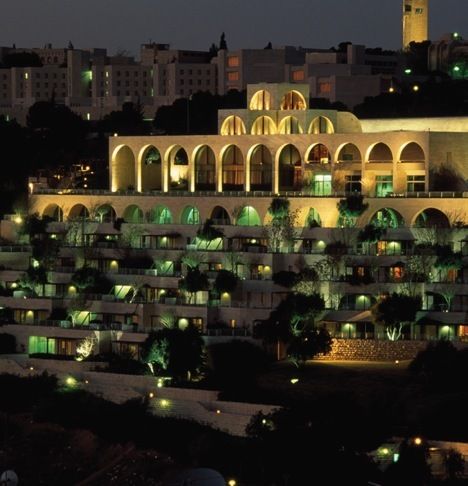

For some time thereafter, no matter how careful we were, some new and usually rather ridiculous charge would still occasionally surface. One amusing instance of this was the accusation published by an Orthodox Jewish newspaper in both Jerusalem and New York during October 1987 that the nefarious Mormons were using their building’s highly visible location to impose a large illuminated cross on the nighttime horizon of Jerusalem. And it was true! (Sort of.) At night, when all the rooms on the sixth level had their lights burning, and when the lights were on in the stairway that runs down the center of the building, an imaginative person could make out a kind of electric cross. Denials that the appearance of a cross was intentional carried no weight with the critics, needless to say. Nor did it help to point out that, in contrast to other Christian groups, Latter-day Saints don’t use the cross in their architecture or liturgy—a fact for which we are routinely assailed and assaulted by Protestant anti-Mormons. Finally, officials of the center simply had to make sure that lights on the sixth level were either turned out or that the windows were covered when they were on.

But these little skirmishes mean little. The battle had been won. The building had been completed, despite intense opposition. What does it mean? Perhaps no one fully knows. Sitting on slightly more than four acres and with a total floor space of 103,420 square feet, Brigham Young University’s Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies is among the most beautiful buildings in Jerusalem and is certainly one of the most visible. (Indeed, it has itself become a tourist attraction that draws thousands of Israelis and their guests each year.) Like a waterfall, it flows down the slope of Mount Scopus. Its many levels are adorned with Italian marble and Burmese teakwood. Its Danish- built organ–created by the venerable firm of Marcussen & Søn, founded in 1806–is one of the finest in the Middle East. From its upper auditorium, where sabbath services are now held for students enrolled in its academic programs and for other local members of the Church and visiting tourists, a breathtaking panoramic view of the Old City of Jerusalem can be seen through three walls of plate-glass windows. Through them, too, the sadness and strife of occupied East Jerusalem can also sometimes be seen, as, behind the pulpit, clouds of tear gas and smoke arise from the ongoing conflicts that occasionally rend the City of Peace.

A community of Latter-day Saints now exists in the Holy Land. It is not a community of agriculturalists and canal-builders, as our ancestors had pictured, but a community of scholars, teachers, and students. In a very real sense, I believe it fulfills the dreams and aspirations of the early missionaries who labored so faithfully in the Near East to build outposts of the kingdom of God in that historic but tortured land. What role the Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies will play in the future of the Church and in the future of the Near East remains to be seen. Perhaps, if we prove worthy of the blessings we have received, it will someday serve the region as a city on a hill, a candle held high to give light to those around it.[1] Whatever benefit it may prove to others, however, it is certainly benefiting us. We can already confidently say that–notwithstanding some periods of reduced occupancy and even closure over the years, owing to both political instability and pandemic–it is building up a new generation of Latter-day Saints to whom the land of Palestine is familiar and for whom the stories of the Bible and the events of the area’s history live in a way they have never lived for our people in the past. If even a small proportion of those who administer and enjoy the programs and courses of the center come away from their experience at Jerusalem with something of the impact that others such as Lorenzo Snow have received, the spiritual life of the Church can only grow in depth and devotion. If even a few return from Palestine with a clearer understanding of our Muslim and Jewish brothers and sisters, our capacity to carry out the mission entrusted to us by the Lord can only increase.

[1] See Matthew 5:14-16.

***

Not everything about the now-mercifully-departed year 2020 was bad. Remarkably, several Arab countries — Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Sudan, and Morocco — have established diplomatic relations with Israel over the past several months, in addition to Egypt and Jordan, which have had such relations since, respectively, 1979 and 1994. There have also been some unprecedented contacts between the Israel and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, though they haven’t yet resulted in the establishment of formal ties. Here are some links that I’ve gathered on the subject (not at all an exhaustive sample):

National Review (15 September 2020): “How Trump Defied the Experts and Forged a Breakthrough in the Middle East: The UAE–Israel deal showed that the conventional wisdom was wrong.”

CNN (16 September 2020): “Two Gulf nations recognized Israel at the White House. Here’s what’s in it for all sides”

Religion Unplugged (16 September 2020): “Will Israel’s Peace Agreements Bring Religious Freedom In The Middle East?”

National Review (18 November 2020): “Iran ‘Ever More Isolated’ as Israel Forges New Ties: Israel and Bahrain take more steps toward the normalization of diplomatic ties”

The Economist (23 November 2020): “Israel and Saudi Arabia send a clear signal to Iran—and Joe Biden: The meaning of a surprising rendezvous”

The Wall Street Journal (27 November 2020)): “Secret Meeting in Desert Between Israeli, Saudi Leaders Failed to Reach Normalization Agreement: Saudi crown prince backed away from U.S.-brokered deal to solidify bulwark against Iran”

National Review (10 December 2020): “Trump Announces Israel and Morocco Agree to Normalize Relations”

Times of Israel (1 January 2021): “UAE, Bahrain delegations take part in Western Wall Hanukkah lighting ceremony: Social activists and opinion leaders from Gulf nations attend event in Jerusalem’s Old City described by Kotel chief rabbi as a ‘Hanukkah miracle’”

The crucial factor for Bahrain and the UAE, in my judgment, and possibly also for the Sudan, is pretty clearly the considerable Arab fear of Iran’s nuclear ambitions and of its naked quest for regional hegemony. Israel, a principal target of Iranian hostility, is a natural (and well-armed and militarily formidable) ally against the Islamic Republic. So Morocco’s entry into full relations with Israel is, in some ways, especially interesting. Morocco is very far away from Israel, which means that the Arab-Israeli conflict has always been, practically speaking, somewhat irrelevant. But Iran is even further away. So perhaps Morocco simply saw an opening and went through it. If so, we can hope that other Arab states will do the same.